| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 14, Number 4, December 2025, pages 130-148

Advanced Electrosurgical Bipolar Vessel Sealing to Control Intraoperative Bleeding in Hysterectomy: A Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis

Greg M. Hammonda, c, Rebecca Boycea, Nathan Bromhama, Ryan Millera, Elise Haslera, Miroslava Slavskab

aHealth Technology Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK

bDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Gwent Hospital, Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, Newport, Wales, UK

cCorresponding Author: Greg M. Hammond, Health Technology Wales, Velindre University NHS Trust Headquarters, Park Nantgarw, CF15 7QZ, UK

Manuscript submitted October 6, 2025, accepted December 1, 2025, published online December 11, 2025

Short title: ABVS in Hysterectomy: A Rapid Review

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1553

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Controlling intraoperative bleeding during hysterectomy is crucial and various methods exist to do this. Advanced electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing (ABVS) may lead to improved outcomes compared to other hemostatic techniques. This rapid review aims to address the question “what is the clinical and cost effectiveness of ABVS compared with standard care for controlling intraoperative bleeding in hysterectomy?”

Methods: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, KSR Evidence, Cochrane Library, and the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) HTA database were searched up to February 2025. Forward citation searching of included studies was conducted in Scopus. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing ABVS to standard care for controlling intraoperative bleeding during abdominal, laparoscopic, or vaginal hysterectomies were included. Outcomes extracted included blood loss, operative time, complications, length of hospital stay, patient-reported pain, blood transfusions, health-related quality of life, resource use, and economic outcomes. Meta-analyses were conducted for each type of hysterectomy and pooled effect sizes were analyzed. Studies were synthesized narratively if not included in meta-analyses.

Results: One systematic review, one HTA, and 15 RCTs met the eligibility criteria. Meta-analyses found statistically significant differences in favor of ABVS over suturing for vaginal hysterectomy operative time and patient-reported pain the evening after surgery, abdominal hysterectomy blood loss and risk of requiring blood transfusion, and in favor of ABVS over conventional electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing for total laparoscopic hysterectomy operative time. Two studies showed significantly lower blood loss with ABVS during subtotal laparoscopic hysterectomy. There were no statistically significant differences in other outcomes. A cost-consequence analysis from the UK perspective demonstrated high upfront costs associated with ABVS; however, potential cost savings were associated with reduced suture usage and lengths of hospital stay.

Conclusions: Use of ABVS during hysterectomy may lead to some improved outcomes compared to suturing or other energy devices; however, many outcomes are similar between methods. A lack of economic evidence means economic consequences are uncertain. Use of ABVS should be based on the type of hysterectomy performed, complexity of individual patients, and surgeons’ familiarity with devices.

Keywords: Hysterectomy; Bleeding; Electrosurgery; Vessel sealing; Rapid review

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Approximately 40,000 hysterectomies are carried out by the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales every year [1, 2]. There are three main routes for performing a hysterectomy: abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal. It is important to control intraoperative bleeding during hysterectomy and the current standard of care for this during abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy is suturing, monopolar electrosurgery, or conventional electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing (cEBVS). For laparoscopic hysterectomy, advanced EBVS (ABVS) is the current standard of care.

ABVS devices have been developed to improve on cEBVS by measuring tissue impedance and using higher current and lower voltage, which allow for tissue cooling [3]. By measuring tissue impedance, devices can automatically adjust voltage and current to ensure adequate hemostatic vessel sealing whilst limiting the amount of lateral thermal spread [3, 4]. Devices can also use impedance measurement to automatically switch off the current when hemostasis is achieved. ABVS devices can be used on vessels and tissue bundles up to 7 mm thick, compared to just 2 mm for cEBVS. Some devices have an incorporated knife in the sealing jaws, which allows sealing and dissecting of tissue with one instrument. The proposed benefits of using ABVS during hysterectomy include reduced blood loss, shorter operative times, quicker recovery for patients, and less time spent in hospital.

The aim of this rapid review was to examine the available evidence to answer the review question “what is the clinical and cost effectiveness of ABVS compared with standard care for controlling intraoperative bleeding in hysterectomy to inform guidance on the use of ABVS for hysterectomy in NHS Wales?”

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Literature search

The systematic search followed Health Technology Wales’ (HTW) standard rapid review methodology [5]. Searches were undertaken by an information specialist (EH) of Medline, Embase, CINAHL, KSR Evidence, Cochrane Library, and the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) HTA database. The searches were carried out during September 12 - 17, 2024, with an update search of all databases on February 3, 2025, with no date limits. At the same time as the update search, forward citation searching of the studies included in this review was conducted in Scopus. All search strategies are available in Supplementary Material 1 (jcgo.elmerpub.com).

Study eligibility

Eligibility criteria used to select evidence are outlined in Table 1. As this was a rapid review, article titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by one author (GMH). Full texts of potentially relevant studies were screened by GMH against the eligibility criteria. Where there was uncertainty about an article’s inclusion, it was discussed with another author (NB). Economic studies were screened by a single reviewer (RB) and where there was uncertainty about inclusion, this was discussed with another author (RM). Evidence from HTAs, systematic reviews (SRs), and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was prioritized, in line with rapid review methodology. Additionally, evidence was reviewed separately by type of hysterectomy. Published studies in the English language were eligible, with conference proceedings excluded. Formal risk of bias assessment was not performed, according to HTW’s rapid review methodology; however, comments on the reliability of studies are included in data tables and highlighted as areas of uncertainty.

Click to view | Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Evidence Included in the Review |

Data extraction

Clinical and economic outcome data were extracted by GMH and RB, respectively, and extraction was checked by NB and RM. Data that were extracted included author, year, study design, study period, setting, sample size, participant characteristics, eligibility criteria, intervention, comparison, and outcomes.

Outcomes reported in this review include blood loss, operative time, length of hospital stay (LOS), patient-reported pain, complications, blood transfusions, and quality of life (QoL).

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

In this review, the meta-analysis of vaginal hysterectomy reported by Balgobin et al [6] was updated and new pair-wise meta-analyses were conducted for laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy. Meta-analyses were performed using the meta package in R version 4.4.1 with RStudio (PositSoftware, PBC). Results were expressed as mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous outcomes and as risk ratios for requirement for blood transfusion. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, and results interpreted by examining the effect size. Outcomes and studies that could not be included in meta-analyses were synthesized narratively.

The MD and 95% CI reported in the SR [6] were used for the updated meta-analysis. For meta-analyses for laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy, means and standard deviations (SDs) were used to calculate MD and standard errors, which were then used in the analyses. Where median and range were reported, these were converted to mean and SD using methods developed by Hozo et al [7]. For meta-analyses of operative time, total operative times were used. For one study [8], missing data for total operative time led to primary operative time being used.

Due to the identified between-study heterogeneity, random effects models were used to pool effect sizes. For continuous outcomes, the restricted maximum likelihood estimator method was used to calculate the heterogeneity variance tau2. For dichotomous data, the inverse variance method was used to calculate weightings, and the Paule-Mandel method was used to calculate tau2. Hartung-Knapp adjustments were used to calculate the CI around pooled effects.

Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. Where high levels of heterogeneity were identified (I2 > 50%), we ran subgroup analyses if possible. Where not possible, this has been noted as a source of uncertainty in the evidence.

| Results | ▴Top |

Literature search

A total of 2,622 titles and abstracts were screened (Supplementary Material 2, jcgo.elmerpub.com). Eighty-four full texts were screened and 17 (one HTA, one SR, and 15 RCTs) met the eligibility criteria for this review.

For vaginal hysterectomy, one SR and meta-analysis was identified comparing “pedicle sealing technologies” to suturing [6]. Two RCTs were also identified [9, 10]. We re-ran the meta-analysis from the SR to exclude non-randomized trials and studies of ultrasonic devices, and added one of the later RCTs [9]. Ten RCTs [9, 11-19] were included in updated meta-analyses. Seven studies investigated LigaSure (Medtronic Ltd, Minneapolis) and three investigated BiClamp (Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen). One study [20] in Balgobin’s review was incorrectly classified as an RCT; this study has been excluded. The study by Ray et al [10] could not be included in the meta-analysis because results were reported as medians with interquartile range (IQR). An HTA was identified [21]; however, clinical effectiveness outcomes were not extracted due to overlap with the SR. Results of the cost analysis in this HTA are discussed.

For laparoscopic hysterectomy, seven RCTs were identified. Studies compared LigaSure to cEBVS [8, 22, 23], UltraCision harmonic shears [24] (Miconvey, Chongqing), and unspecified harmonic scalpel and bipolar shears [25]. One study compared EnSeal (Ethicon, New Jersey) to cEBVS [26], and another compared BiCision (Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen) to UltraCision [27]. Due to the variety of devices, meta-analysis was only possible for the four studies comparing ABVS to cEBVS. Meta-analyses results and evidence from remaining studies have been narratively synthesized.

For abdominal hysterectomy, six RCTs were identified [28-33], all comparing LigaSure to suturing. New meta-analyses were conducted for outcomes where data allowed.

Supplementary Materials 3 and 4 (jcgo.elmerpub.com) give full details of included studies and outcomes are shown in Table 2 [8-10, 22-33].

Click to view | Table 2. Outcomes Reported in Included RCTs |

Vaginal hysterectomy

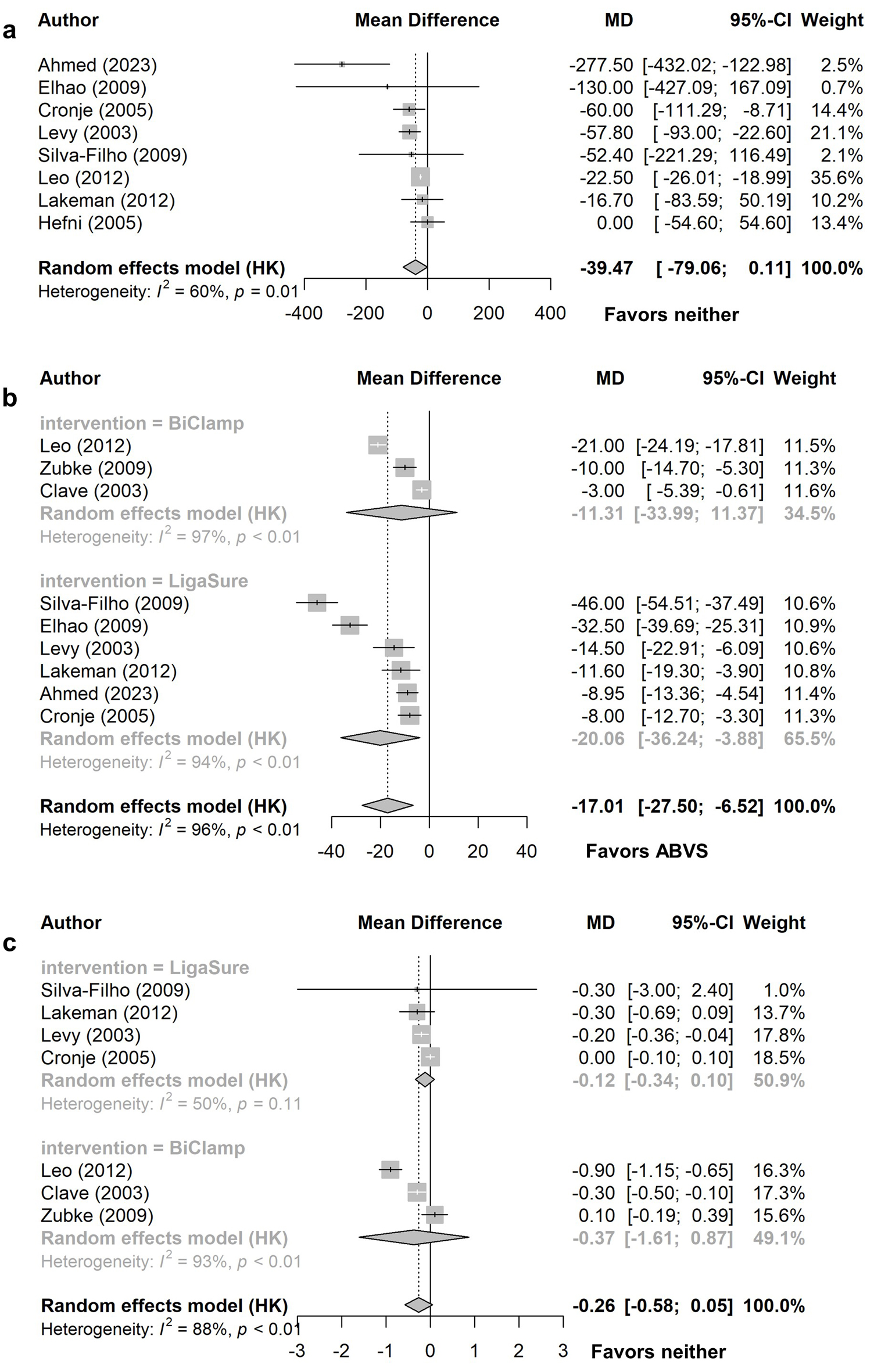

Operative time was statistically significantly shorter with ABVS than suturing in meta-analyses (Fig. 1b). The pooled MD (n = 747) was -17.01 (95% CI: -27.50 to -6.52) min. The heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 96%), but all individual studies showed significant benefit with ABVS. Subgroup analysis based on device type was performed. For BiClamp, operative time was not statistically significantly different (MD -11.31 (95% CI: -33.99 to 11.37) min); however, it was statistically significantly shorter with LigaSure compared to suturing (MD -20.06 (95% CI: -36.24 to -3.88) min). Heterogeneity was still very high in both subgroup analyses at I2 = 97% and 94%, respectively.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Vaginal hysterectomy comparison of ABVS to conventional sutures: (a) blood loss (ml), (b) operative time (min), (c) length of hospital stay (days). ABVS: advanced electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing; CI: confidence interval; HK: Hartung-Knapp adjustment; MD: mean difference. |

There was no significant difference between ABVS and sutures in the meta-analyses for blood loss or LOS. The pooled MD in blood loss (n = 637) was -39.47 (95% CI: -79.06 to 0.11) mL, with substantial heterogeneity (Fig. 1a). The MD in LOS (n = 596) was -0.26 (95% CI: -0.58 to 0.05) days (Fig. 1c). Heterogeneity was high in this analysis (I2 = 88%); therefore, subgroup analysis was performed by ABVS device. There was no statistically significant difference with either device compared to suturing. Heterogeneity was very high in the BiClamp subgroup (I2 = 93%), and notably lower in the LigaSure subgroup (I2 = 50%), suggesting most of the heterogeneity in the main analysis came from studies examining BiClamp.

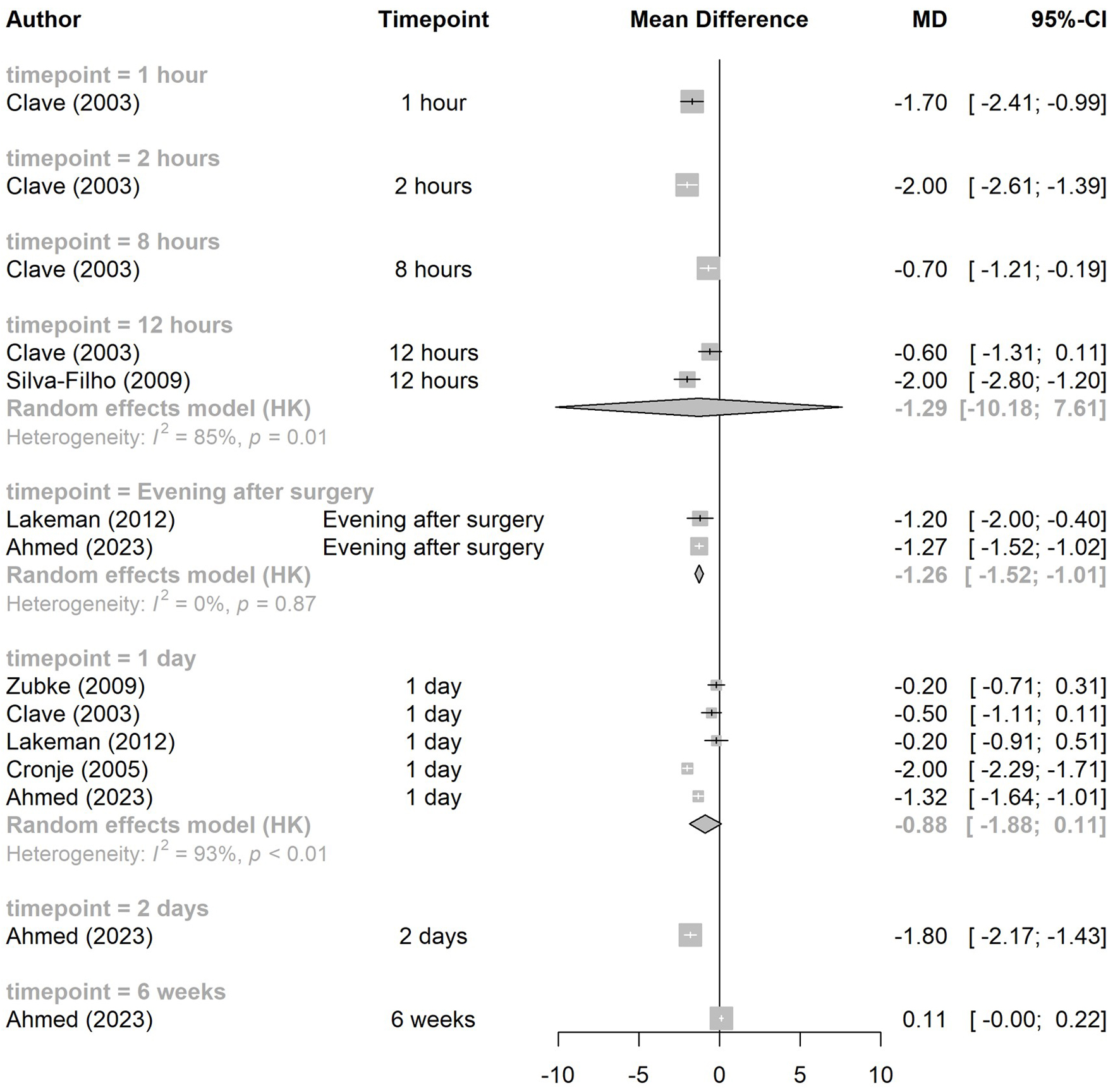

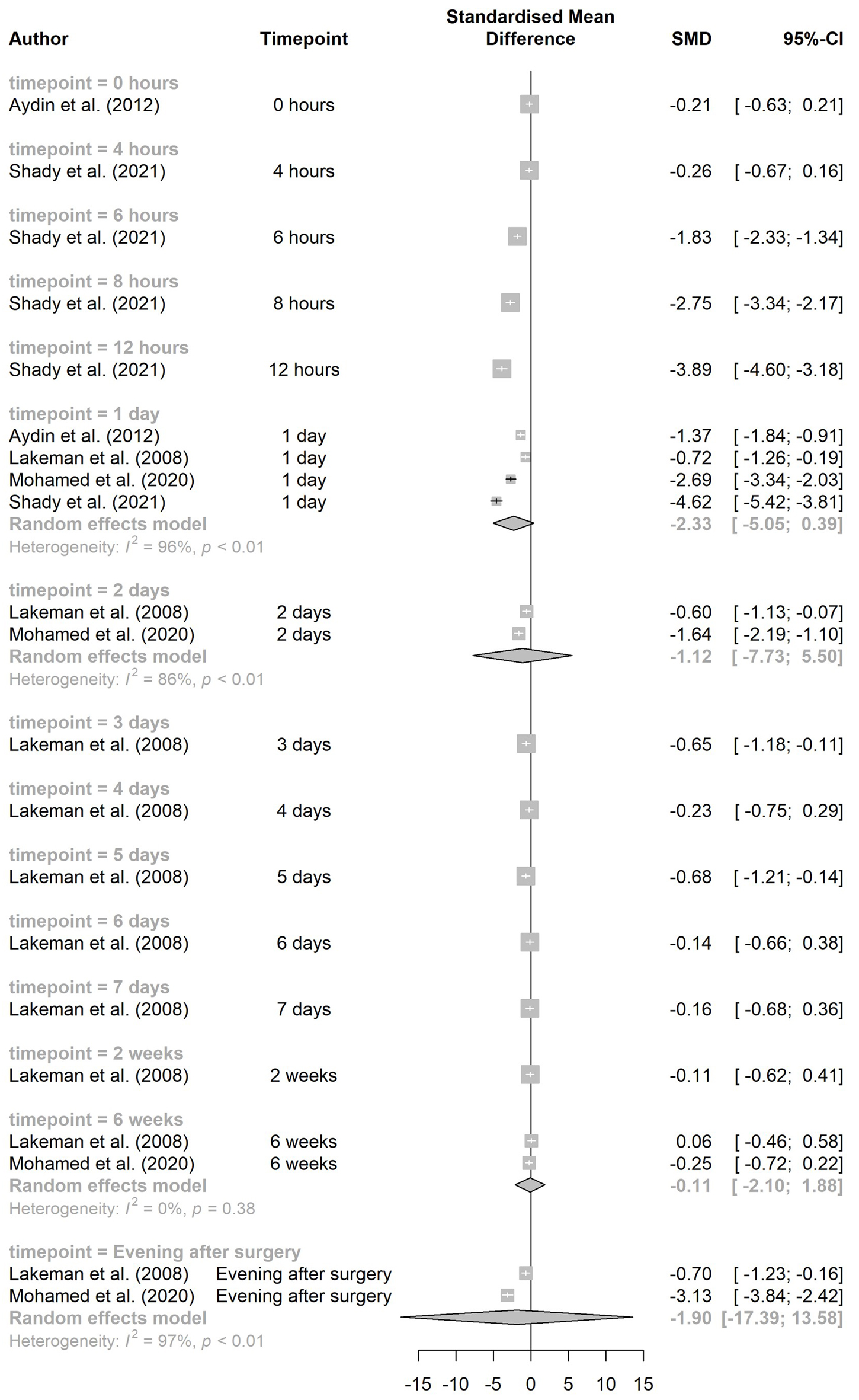

Six RCTs (n = 509) assessed postoperative patient-reported pain. This was reported at several timepoints, and pooled analyses were only possible at three of these. No details of the used visual analogue scales (VAS) were reported. The meta-analysis showed a significant difference in postoperative pain at the “evening after surgery” timepoint, favoring ABVS (Fig. 2). One study found statistically significantly lower pain scores with ABVS compared with suturing at 1, 2, and 8 h postoperatively [17] and another favored ABVS at 2 days postoperatively [9]. There was no significant difference in pain scores at 12 h, 1 day or 6 weeks postoperatively. Heterogeneity was high in the 12-h and 1-day meta-analyses (I2 = 85% and 93%, respectively), whilst there was no heterogeneity in the “evening after surgery” analysis.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Vaginal hysterectomy comparison of ABVS to conventional sutures: patient-reported pain. CI: confidence interval; HK: Hartung-Knapp adjustment; MD: mean difference. |

Balgobin et al reported that the individual studies included in their SR were insufficiently powered to detect differences in complications [6]. Ahmed et al and Ray et al reported no statistically significant difference in complication rates between LigaSure and suturing [9, 10] (Supplementary Material 5, jcgo.elmerpub.com).

The SR did not report blood transfusions. Ahmed et al reported no blood transfusions in the LigaSure group and one in the suturing group (P = 0.487) [9]. Neither the SR, nor the two RCTs, reported QoL. In the study by Ray et al [10], there was no significant difference in any outcomes (Table 2).

Laparoscopic hysterectomy

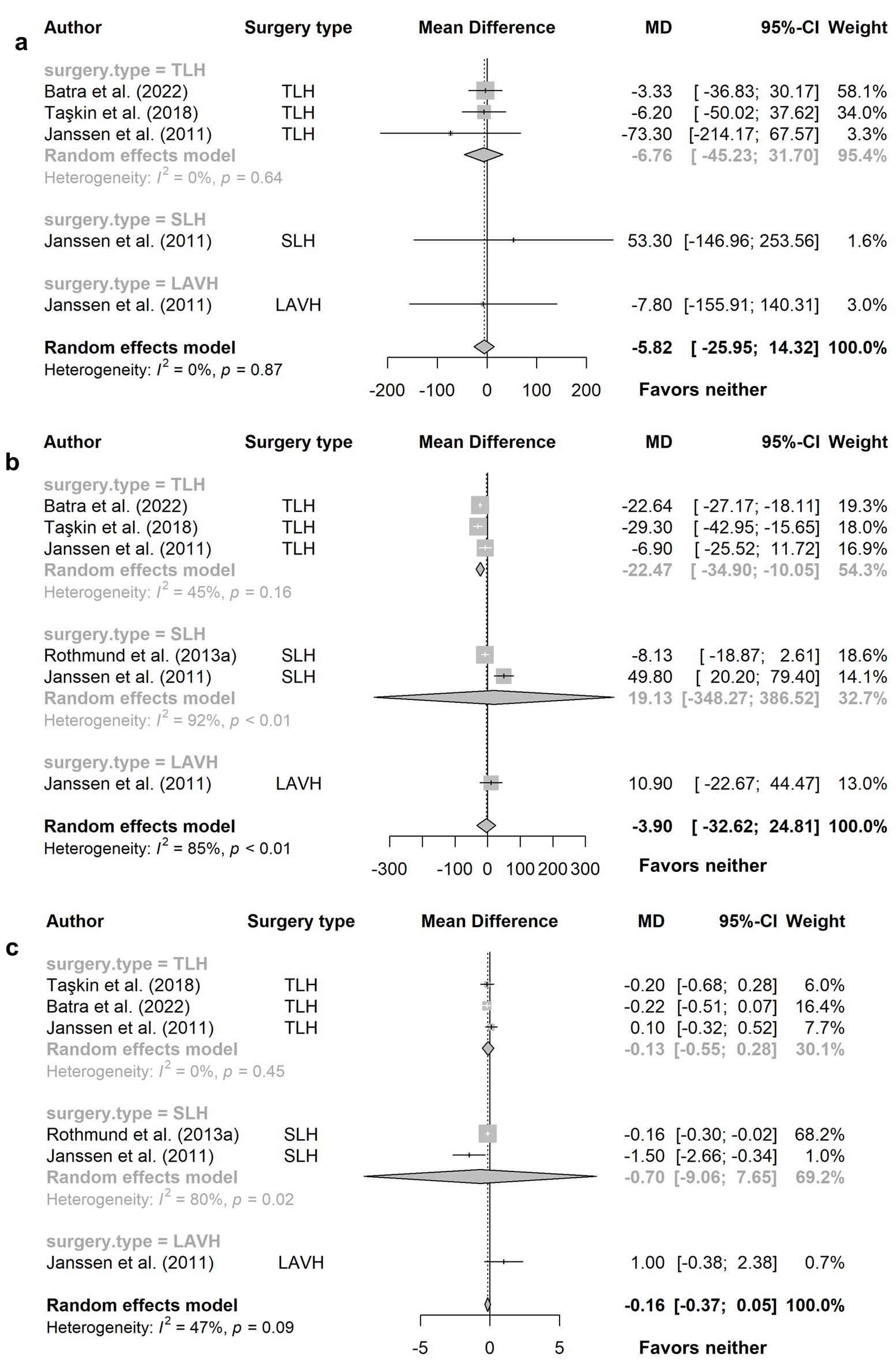

Results were analyzed separately for total (TLH) and subtotal (SLH) laparoscopic hysterectomies. The meta-analysis found no statistically significant difference in blood loss during TLH between ABVS and cEBVS (Fig. 3a, n = 275, MD -6.76 (95% CI: -45.23 to 31.70) mL). There was no heterogeneity. When results for all types of laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH, SLH, and laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH)) were pooled (n = 319), there was no significant difference in blood loss and no heterogeneity. Three studies reported intraoperative blood loss during SLH (Table 2). One found patients experienced significantly less blood loss with EnSeal than cEBVS [26]. When comparing BiCision to UltraCision harmonic scalpel, another study found the overall intraoperative blood loss score was significantly lower with BiCision (1.07 ± 0.25 vs. 1.63 ± 0.49, P < 0.0001), indicating less blood loss [27]. In contrast, the third study found higher blood loss with LigaSure than cEBVS during SLH, but statistical significance was not reported [22]. Janssen et al reported intraoperative blood loss during LAVH was 7.8 mL lower with LigaSure than cEBVS [22].

Click for large image | Figure 3. Laparoscopic hysterectomy comparison of ABVS to conventional EBVS: (a) blood loss (mL), (b) operative time (min), (c) length of hospital stay (days). CI: confidence interval; LAVH: laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy; MD: mean difference; SLH: subtotal laparoscopic hysterectomy; TLH: total laparoscopic hysterectomy. |

Meta-analysis of studies comparing ABVS to cEBVS during TLH showed operative time was significantly shorter with ABVS (Fig. 3b, n = 275, MD -22.47 (95% CI: -34.90 to -10.05) min), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 45%). Operative time was shorter with LigaSure when comparing to harmonic scalpel and bipolar shears during TLH; however, no statistical analyses were reported [25]. Two studies, comparing ABVS to cEBVS during SLH (n = 183), were included in meta-analyses (Fig. 3b). Operative time was not statistically significantly different (MD 19.13 (95% CI: -348.27 to 386.52) min). Heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 92%) and these studies used different ABVS devices. In a self-controlled study, Rothmund et al found no significant difference between BiCision and UltraCision in surgical time from first coagulation and cutting of cornual structures until complete preparation of each parametrial side during SLH (Table 2) [27]. However, Ashraf et al found SLH took less than half the time with LigaSure compared to UltraCision (64.15 ± 12.02 vs. 138.25 ± 23.41 min, P < 0.005) [24]. Rothmund et al also reported differences in a breakdown of SLH surgical time [26]. Two of these timeframes were not significantly different, but the time from first coagulation and cutting of cornual structures to complete preparation of each parametrial side directly before cervical detachment was significantly shorter with EnSeal than cEBVS (MD -11.33 (95% CI: -17.84 to -4.83) min, P < 0.001). Janssen et al reported both total operative time and operative time to detachment of the uterus were longer with LigaSure than cEBVS during LAVH [22]. Meta-analysis of TLH, SLH, and LAVH combined (Fig. 3b, n = 479) found no statistically significant difference in operative time between ABVS and cEBVS (MD -3.90 (95% CI: -32.62 to 24.81) min, I2 = 85%).

There was no significant difference in LOS in the meta-analyses of all types of laparoscopic hysterectomy combined (n = 479), TLH alone (n = 275), or SLH alone (n = 183) with ABVS or cEBVS (Fig. 3c). One study found no significant difference between LigaSure and UltraCision during SLH (1.65 ± 0.58 vs. 2.00 ± 1.52 days, P = 0.354) [24]. LOS in a study comparing LigaSure with harmonic scalpel and bipolar shears were similar; however, no statistical analyses were reported [25]. For LAVH, LOS was 1 day shorter after LigaSure compared with cEBVS [22].

Two studies reported postoperative pain. No statistically significant differences in patient-reported pain were found after TLH with either LigaSure or cEBVS at 8 or 24 h [23] (Table 2). There were no significant differences between EnSeal and cEBVS at 1, 2, and 3 days after SLH [26] (Table 2). Pain scores were mild for both groups in each study.

Low numbers of complications were reported in all studies and numbers were generally similar between groups (Supplementary Material 5, jcgo.elmerpub.com), with no statistically significant differences reported [8, 22, 24]. In the self-controlled study comparing SLH with BiCision or UltraCision, two patients reported bleeding during follow-up [27]. However, as patients acted as their own controls, it is not possible to attribute complications to either intervention.

One study found two patients required blood transfusion during TLH with LigaSure compared to four with cEBVS (P = 0.669) [23]. No transfusions were required in either group in the study comparing SLH with EnSeal or cEBVS [26]. No patients in the self-controlled study comparing BiCision and UltraCision required blood transfusion [27].

No evidence on QoL was identified.

Abdominal hysterectomy

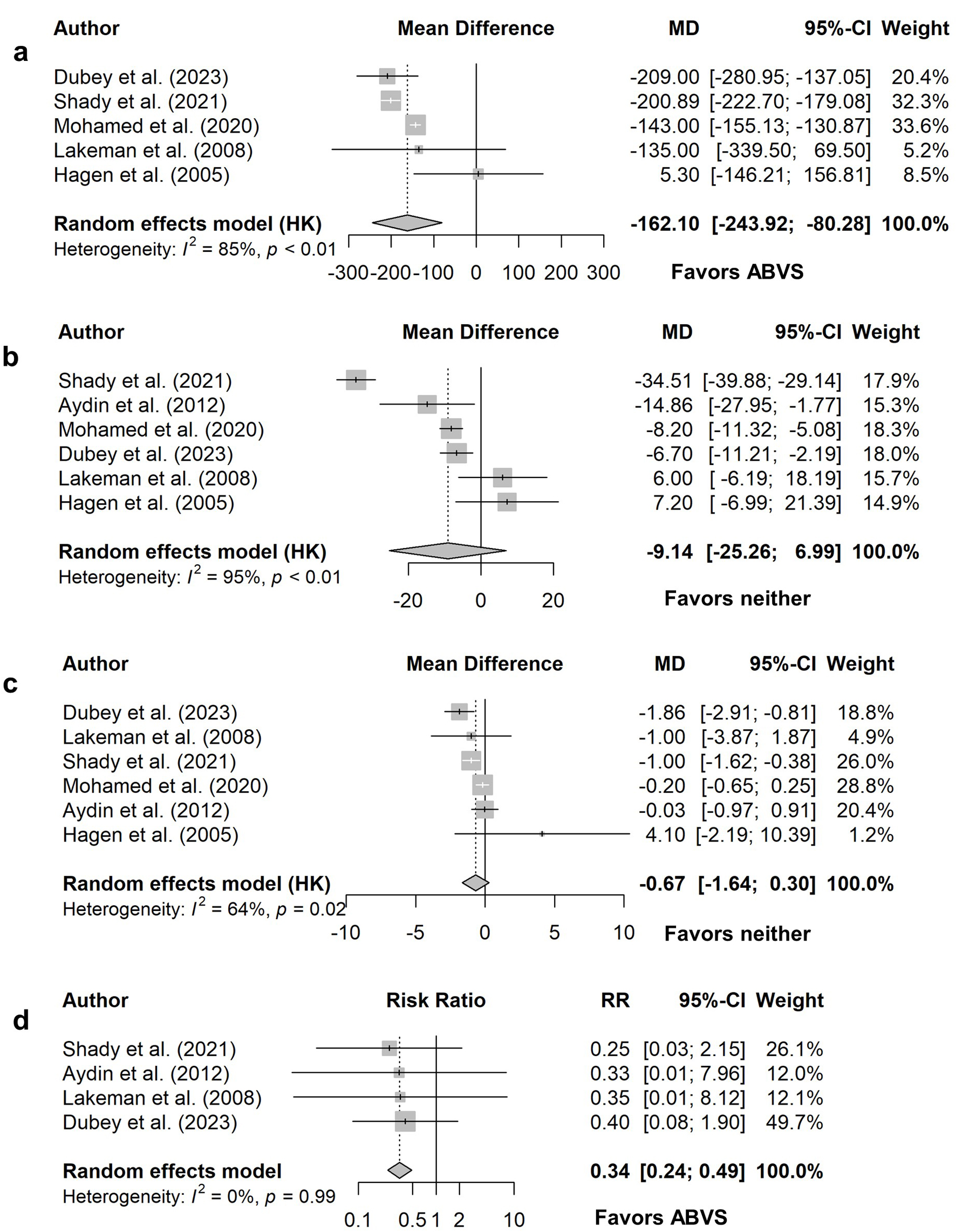

Meta-analyses found statistically significant differences in favor of LigaSure over suturing for intraoperative blood loss and the risk of requiring a blood transfusion. The pooled MD in blood loss (n = 307) was -162.10 (95% CI: -243.92 to -80.28) mL (Fig. 4a) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 85%). The pooled risk ratio for requiring blood transfusion (n = 295) was 0.34 (95% CI: 0.24 to 0.49), indicating a lower risk when LigaSure is used compared to suturing (Fig. 4d). There was no heterogeneity in this analysis; however, there was no significant difference in the number of blood transfusions that occurred in either group in all four studies.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Abdominal hysterectomy comparison of ABVS to conventional suturing: (a) blood loss (mL), (b) operative time (min), (c) length of hospital stay (days), (d) blood transfusion required. For length of hospital stay reported by Dubey, only means for each group and a P value of 0.000 were reported; the MD and standard error were estimated by taking a conservative exact P value of 0.00049. ABVS: advanced electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing; CI: confidence interval; HK: Hartung-Knapp adjustment; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio. |

Meta-analyses estimated no significant difference between LigaSure and suturing for operative time (Fig. 4b, n = 395, MD -9.14 (95% CI: -25.26 to 6.99) min), LOS (Fig. 4c, n = 395, MD -0.67 (95% CI: -1.64 to 0.30) days), or patient-reported pain at “evening after surgery”, 1-day, 2-day, and 6-week timepoints (Fig. 5). Heterogeneity was substantial or high for all analyses, except patient-reported pain at 6 weeks for which there was no heterogeneity. Differing VAS were used to assess postoperative pain, therefore SMD was used in the meta-analysis. Single studies showed no significant difference in pain scores immediately postoperatively [28], at 4 h [33], and days 3 to 7 and 14 [31]. However, one study found scores were significantly lower in the LigaSure group at 6, 8, and 12 h postoperatively (P = 0.0001 for all) [33]. One study reported modal patient pain scores at days 1, 2, and 3 postoperatively and scores were higher in the suturing group at all timepoints [29] (Table 2).

Click for large image | Figure 5. Abdominal hysterectomy comparison of ABVS to conventional suturing: patient-reported pain. CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardized mean difference. |

Five studies reported complications during or after abdominal hysterectomy and similar rates were reported in all studies [28, 30-33] (Supplementary Material 5, jcgo.elmerpub.com). These were generally events such as wound infection, injury to adjacent structures, or bleeding. No statistically significant differences in complication rates were reported.

One RCT assessed QoL after ABVS or sutures and scores were similar across all RAND-36 domains for both groups at 6 months postoperatively [31]. However, full data were not reported.

Economic literature review

Of 2,622 articles screened, four were deemed potentially relevant from an economic perspective. Full texts of these studies were reviewed against eligibility criteria and one study, an HTA by the Centre for Evidence-based Purchasing (Table 3), was included [21].

Click to view | Table 3. Summary of the Included Economic Study |

Informed by a literature review and expert opinion, a cost-consequence analysis was conducted from the UK perspective to compare ABVS use to suturing during vaginal hysterectomy.

Within their literature review, three RCTs reported a reduced LOS with ABVS compared to suturing. However, due to variations reported in expected reductions, this input was informed by three UK experts. The economic analysis explored potential cost savings associated with a reduced LOS of 1, 2 or 3 days.

The analysis considered using ABVS would reduce the number of sutures required by six per case [11]. Although the literature review noted significant reductions in procedure time with ABVS, this was not assumed to translate to cost savings due to the rationale that theater schedules are fixed in duration, and so reduced operating time would not impact the number of surgeries performed.

Costs for ABVS systems were provided by manufacturers and include the system itself, reusable handpieces, and single use forceps or electrodes. Decontamination of instruments was assumed to cost £1.05 each. The daily cost of a hospital bed was sourced from the Personal Social Services Research Unit, and suture costs were sourced from Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust.

Results of the analysis demonstrate high upfront costs associated with the purchase of ABVS systems, ranging from £9,307 to £28,131 for the generator, and between £14 and £241 for forceps per case. However, cost savings associated with sutures of £10.58 per case could be realized using ABVS. A reduced LOS of 1, 2 or 3 days could reduce costs by £243, £486 or £729, respectively.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Overall, our pooled findings show the clinical effectiveness of ABVS appears to be non-inferior to sutures during vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy and to cEBVS or other energy-based vessel sealing devices during laparoscopic hysterectomy. ABVS use may lead to lower blood loss during abdominal hysterectomy and SLH, shorter operative time during vaginal hysterectomy and TLH, and lower risk of requiring a blood transfusion during abdominal hysterectomy. Patient-reported pain seems to be lower in the first few hours after abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy with ABVS compared to suturing; however, this effect diminishes by 1 day postoperatively. LOS and complication rates are similar between ABVS and comparators for all routes of hysterectomy. Patient-reported pain is also similar between ABVS and other energy devices after laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Comparison of our findings with those of other SRs shows variability in the reported performance of ABVS devices for hysterectomy, though performance generally seems to be similar to suturing or other energy devices. Balgobin et al [6] included RCTs and observational studies in their meta-analysis comparing ABVS and ultrasonic devices to suturing during vaginal hysterectomy, and found that the devices led to significant improvements in blood loss, operative time, LOS, and patient-reported pain at several timepoints. This is different to our findings that only operative time was significantly better with ABVS, as well as patient-reported pain at some earlier timepoints. Observational studies and studies on ultrasonic devices accounted for between 43% and 50% of the weighting in Balgobin et al’s meta-analyses and several of these reported the largest effect sizes in favor of ABVS/ultrasonic devices, thus this may account for the difference in findings. Another recent SR of vaginal hysterectomy included a network meta-analysis of RCTs and observational studies [34]. Pairwise comparisons of BiClamp and LigaSure to clamping/suturing of vessels found significant differences in favor of ABVS for total operative time with LigaSure, blood loss for both devices, and pain at 24 h postoperatively for LigaSure.

No SRs looking solely at ABVS during abdominal hysterectomy were identified; however, there is a meta-analysis including vaginal (10 studies), abdominal (two studies), and laparoscopic (one study) hysterectomies [35]. This review examined RCTs of several methods to control bleeding and found that LigaSure led to significantly reduced blood loss compared to suturing for all types of hysterectomy combined. However, this reduction was not statistically significant in subgroup analyses of vaginal and abdominal hysterectomies. Additionally, some included studies were misclassified as investigating cEBVS though they used LigaSure, thus these studies’ results are missing from the meta-analysis estimates. There were errors in all of the SRs discussed above, including misclassification of studies or interventions, inappropriate pooling of studies, and errors in reporting results.

For laparoscopic hysterectomy, there have been two recent meta-analyses. Both included RCTs and observational studies but included fewer RCTs comparing ABVS to other methods than we identified. Zorzato et al pooled studies comparing ABVS and cEBVS for TLH (two RCTs, two observational studies) [36]. One RCT investigated ABVS during vaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (vNOTES) and was excluded from our analyses. The meta-analyses found blood loss and operative time were significantly lower with ABVS; however, the study on vNOTES contributed a large proportion of the weighting. There was no significant difference in LOS. Horton et al included two RCTs and two observational studies comparing LigaSure to cEBVS, one RCT and one observational study comparing EnSeal to cEBVS, and three observational studies comparing PlasmaKinetic to cEBVS in their meta-analyses [37]. The authors did not pool the different ABVS devices together and found that blood loss and operative time were significantly lower with PlasmaKinetic but not significantly different with LigaSure or EnSeal. Our meta-analyses only found a significant difference in operative time for TLH, with ABVS being quicker. Some individual studies also found significant differences in outcomes.

There are several areas of uncertainty from the evidence identified. Studies measured outcomes in different ways, including using different start and end points for operative time or LOS calculations, using different methods to evaluate blood loss, and using varying VAS for patient-reported pain. Some results may not be comparable for some outcomes and details of how outcomes were measured are missing from several studies. Several studies are described as underpowered to detect differences in outcomes and it is uncertain whether some statistically significant differences would be considered clinically significant and lead to modifications or improvements in clinical practice. The majority of included studies investigated LigaSure (19 of 24 RCTs); it is unclear whether other devices’ performance would be similar to LigaSure. Additionally, due to the age of some studies, these may have used older generations of ABVS technology that may not have the same performance standards as currently available devices. For vaginal hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy, only studies comparing ABVS to suturing were identified. It is therefore unknown how ABVS compares to other methods of vessel sealing; however, suturing is the most commonly used method in these procedures. For laparoscopic hysterectomy, ABVS is already commonly used and only studies comparing ABVS to cEBVS or other energy devices were identified. Most studies only included patients undergoing hysterectomy for benign conditions; only two studies included patients with malignant disease. Therefore, the generalizability of evidence to patients undergoing hysterectomy for malignant disease is uncertain.

The identified economic analysis does not provide a cost per case of ABVS systems, and so it is not possible to estimate whether they are likely to be overall cost saving or cost incurring. It is uncertain whether outcomes used in the analysis are based on statistically significant differences identified in the clinical evidence review. Additionally, no sensitivity analyses are presented, so uncertainty has not been captured.

Limitations

This rapid review is subject to inherent limitations of rapid review methodology. Having a single reviewer sifting the literature and extracting data means a risk of some relevant studies and outcomes being missed. Checking by a second reviewer and consulting subject experts on relevant additional studies were in place to mitigate this. There were also several limits to our eligibility criteria that may have led to potentially relevant studies being excluded. Due to the large evidence base available, we restricted to SRs and RCTs; however, there is a large body of observational evidence as seen in other recent SRs. This has led to some differences in the results of our meta-analyses compared to others, though we have included studies that should be at lower risk of confounding factors. We have not performed formal risk of bias assessment, in line with HTW’s rapid review methodology, thus this cannot be commented on. There was substantial heterogeneity in the majority of meta-analyses reported in this review and subgroup analysis was only possible in certain cases to assess the impact of this.

Conclusions

The use of ABVS during hysterectomy may lead to some improved outcomes compared to suturing or other energy devices; however, many outcomes are similar between ABVS and other methods. A lack of economic evidence means economic consequences are uncertain. Use of ABVS devices should be based on the type of hysterectomy performed, the potential complexity of individual patients, and surgeons’ familiarity/skill/preference.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Search strategies.

Suppl 2. PRISMA diagram.

Suppl 3. Design and characteristics of the included systematic review.

Suppl 4. Design and characteristics of the included randomized controlled trials.

Suppl 5. Complications reported in the included RCTs.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

Health Technology Wales is funded by Welsh Government and hosted by NHS Wales but is independent of both.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

GMH developed the PICO, review of clinical effectiveness evidence and writing of introduction, methods, clinical effectiveness results, and discussion. RB developed the PICO, review of economic evidence and writing of economic evidence results and discussion. NB developed the PICO, quality assurance of clinical evidence review, review and editing of manuscript. RM developed the PICO, quality assurance of economic evidence review, review and editing of manuscript. EH conducted all searches, review and editing of manuscript. MS review and editing of manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

ABVS: advanced electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing; AH: abdominal hysterectomy; BMI: body mass index; cEBVS: conventional electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing; CI: confidence interval; CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EBVS: electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing; HK: Hartung-Knapp adjustment; HTA: health technology assessment; HTW: Health Technology Wales; INAHTA: International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment; IQR: interquartile range; ITT: intention-to-treat; KSR Evidence: Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Evidence; LAVH: laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy; LH: laparoscopic hysterectomy; LOS: length of hospital stay; MD: mean difference; NHS: National Health Service; NR: not reported; OT: operative time; PASA: Purchasing and Supply Agency; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; PSSRU: Personal Social Services Research Unit; QoL: quality of life; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error; SLH: subtotal laparoscopic hysterectomy; SMD: standardized mean difference; SR: systematic review; TLH: total laparoscopic hysterectomy; VAS: visual analogue scale; vNOTES: vaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery

| References | ▴Top |

- Digital Health and Care Wales (DHCW). Annual PEDW data tables: total procedures Welsh providers 2023/24 [DHCW website]. 2024. https://dhcw.nhs.wales/data/statistical-publications-data-products-and-open-data/annual-pedw-data-tables/. Accessed October 1, 2025.

- NHS England. Hysterectomies on patients by age [NHS Digital website]. 2021. [Archived link] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20240503082750/https://digital.nhs.uk/supplementary-information/2021/hysterectomies-on-patients-by-age. Accessed October 1, 2025.

- Bentham GL, Preshaw J. Review of advanced energy devices for the minimal access gynaecologist. Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;23(4):301-309.

- El-Sayed M, Mohamed S, Saridogan E. Safe use of electrosurgery in gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;22(1):9-20.

- Health Technology Wales (HTW). Appraisal process guide [HTW website]. 2024. https://healthtechnology.wales/wp-content/uploads/Appraisal-Process-Guide.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2025.

- Balgobin S, Balk EM, Porter AE, Misal M, Grisales T, Meriwether KV, Jeppson PC, et al. Enabling technologies for gynecologic vaginal surgery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2024;143(4):524-537.

doi pubmed - Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13.

doi pubmed - Batra S, Bhardwaj P, Dagar M. Comparative analysis of peri-operative outcomes following total laparoscopic hysterectomy with conventional bipolar-electrosurgery versus high-pressure pulsed LigaSure use. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2022;11(2):105-109.

doi pubmed - Ahmed ES, Midan MF, Elbassioune WM. Comparative study of bipolar vessel sealing clamp versus traditional method for vaginal hysterectomy. Int J Med Arts. 2023;5(8):3486-3494.

- Ray MM, Crisp CC, Pauls RN, Hoehn J, Lewis K, Bonglack M, Yeung J. Use of a vessel sealer for hysterectomy at time of prolapse repair: a randomized clinical trial. Urogynecology (Phila). 2025;31(3):234-242.

doi pubmed - Cronje HS, de Coning EC. Electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing during vaginal hysterectomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91(3):243-245.

doi pubmed - Elhao M, Abdallah K, Serag I, El-Laithy M, Agur W. Efficacy of using electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing during vaginal hysterectomy in patients with different degrees of operative difficulty: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(1):86-90.

doi pubmed - Levy B, Emery L. Randomized trial of suture versus electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):147-151.

doi pubmed - Silva-Filho AL, Rodrigues AM, Vale de Castro Monteiro M, da Rosa DG, Pereira e Silva YM, Werneck RA, Bavoso N, et al. Randomized study of bipolar vessel sealing system versus conventional suture ligature for vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):200-203.

doi pubmed - Lakeman MM, The S, Schellart RP, Dietz V, ter Haar JF, Thurkow A, Scholten PC, et al. Electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing versus conventional clamping and suturing for vaginal hysterectomy: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2012;119(12):1473-1482.

doi pubmed - Hefni MA, Bhaumik J, El-Toukhy T, Kho P, Wong I, Abdel-Razik T, Davies AE. Safety and efficacy of using the LigaSure vessel sealing system for securing the pedicles in vaginal hysterectomy: randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2005;112(3):329-333.

doi pubmed - Clave H, Niccolai P. [Painless hysterectomy: an innovative technique]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2003;32(4):375-380.

pubmed - Leo L, Riboni F, Gambaro C, Surico D, Surico N. Vaginal hysterectomy and multimodal anaesthesia with bipolar vessel sailing (Biclamp((R)) forceps) versus conventional suture technique: quality results' analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(4):1025-1029.

doi pubmed - Zubke W, Hornung R, Wasserer S, Hucke J, Fullers U, Werner C, Schmitz P, et al. Bipolar coagulation with the BiClamp forceps versus conventional suture ligation: a multicenter randomized controlled trial in 175 vaginal hysterectomy patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280(5):753-760.

doi pubmed - Ding Z, Wable M, Rane A. Use of Ligasure bipolar diathermy system in vaginal hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(1):49-51.

doi pubmed - Peirce SC, Crawford DC. Evidence review: electrosurgical vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy [CEP 07019]. NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency: Centre for Evidence-based Purchasing (CEP). 2007. [Link to archive as Centre for Evidence-based Purchasing was dissolved in 2010.] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20100709152226/http://www.pasa.nhs.uk/pasa/Doc.aspx?Path=%5bMN%5d%5bSP%5d/NHSprocurement/CEP/surgicalequip/CEP07019.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2025.

- Janssen PF, Brolmann HA, van Kesteren PJ, Bongers MY, Thurkow AL, Heymans MW, Huirne JA. Perioperative outcomes using LigaSure compared with conventional bipolar instruments in laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2011;118(13):1568-1575.

doi pubmed - Taskin S, Sukur YE, Altin D, Turgay B, Varli B, Baytas V, Ortac F. Bipolar energy instruments in laparoscopic uterine cancer surgery: a randomized study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28(6):645-649.

doi pubmed - Ashraf TA, Gamal M. Bipolar vessel sealer versus harmonic scalpel in laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Gynecol Obstet. 2012;2(5):137.

- Hasabe RA, Hivre M, Khapre S. Comparison between three instruments for total laparoscopic hysterectomy: harmonic scalpel, Ligasure, and bipolar shearer. Int J Acad Med Pharm. 2023;5(3):445-448.

- Rothmund R, Kraemer B, Brucker S, Taran FA, Wallwiener M, Zubke A, Wallwiener D, et al. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy using EnSeal vs standard bipolar coagulation technique: randomized controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):661-666.

doi pubmed - Rothmund R, Szyrach M, Reda A, Enderle MD, Neugebauer A, Taran FA, Brucker S, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical comparison between UltraCision and the novel sealing and cutting device BiCision in patients with laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(10):3852-3859.

doi pubmed - Aydin C, Yildiz A, Kasap B, Yetimalar H, Kucuk I, Soylu F. Efficacy of electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing for abdominal hysterectomy with uterine myomas more than 14 weeks in size: a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;73(4):326-329.

doi pubmed - Dubey P, Dube M, Kanhere A, Biswas N, De R, Koley A, Banerjee PK. Electrothermal vessel sealing versus conventional suturing in abdominal hysterectomy: A Randomised Trial. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e34123.

doi pubmed - Hagen B, Eriksson N, Sundset M. Randomised controlled trial of LigaSure versus conventional suture ligature for abdominal hysterectomy. BJOG. 2005;112(7):968-970.

doi pubmed - Lakeman M, Kruitwagen RF, Vos MC, Roovers JP. Electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing versus conventional clamping and suturing for total abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(5):547-553.

doi pubmed - Mohamed MA, Eid SM, Ayad WA, Emam AAH. Comparative study of electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing using Ligasure versus conventional suturing for total abdominal hysterectomy. Int J Med Arts. 2020;2(4):698-704.

- Shady NW, Farouk HA, Sallam HF. Perioperative outcomes of Ligasure versus standard ligature technique among overweight and obese women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized clinical trial. J Gynecol Surg. 2021;37(4):345-351.

- Bonavina G, Bonitta G, Busnelli A, Rausa E, Cavoretto PI, Salvatore S, Candiani M, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy: a network meta-analysis comparing short-term outcomes of surgical techniques and devices. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024;31(10):825-835.

doi pubmed - Guo T, Ren L, Wang Q, Li K. A network meta-analysis of updated haemostatic strategies for hysterectomy. Int J Surg. 2016;35:187-195.

doi pubmed - Zorzato PC, Ferrari FA, Garzon S, Franchi M, Cianci S, Lagana AS, Chiantera V, et al. Advanced bipolar vessel sealing devices vs conventional bipolar energy in minimally invasive hysterectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(4):1165-1174.

doi pubmed - Horton TS, Coombs PE, Ha Y, Wang Z, Brigham TJ, Ofori-Dankwa ZE, Cardenas-Trowers OO. Electrosurgical devices used during laparoscopic hysterectomy. JSLS. 2024;28(3).

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.