| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 1, March 2026, pages 24-29

The Relationship Between Branched-Chain Amino Acid Levels and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Low-Risk Pregnant Women

Gizem Sayara , Elcin Islek Secenb

, Raziye Desdicioglub

, Ceylan Balc

, Gulsen Yilmazc

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

bFaculty of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ankara Yildirim Beyazit University, Ankara, Turkey

cFaculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Ankara Yildirim Beyazit University, Ankara, Turkey

dCorresponding Author: Gizem Sayar, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

Manuscript submitted November 3, 2025, accepted January 26, 2026, published online February 7, 2026

Short title: Relation Between BCAA and GDM in Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1587

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) represents one of the most prevalent medical complications in pregnancy. The prevalence of GDM in society is increasing. The aim of GDM screening is to make an early diagnosis in order to prevent complications associated with GDM. The aim of our study was to investigate the effectiveness of branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) in the diagnosis of GDM by comparing the second-trimester serum BCAA concentrations between low-risk primigravid women with and without GDM.

Methods: The study included a total of 110 primigravida evenly split between the GDM group (n = 55) and the control group (n = 55). The age, pre-pregnancy and test weights, body mass index, and demographic data of the participating pregnant women were recorded. Serum concentrations of BCAA in the fasting and postprandial states of the pregnant women were measured, and serum BCAA concentrations were compared between groups.

Results: In our study, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of demographic data and anthropometric characteristics. Pregnant women diagnosed with GDM had significantly higher postprandial valine levels compared to the control group, with values of 168.5 ± 46.8 vs. 138.5 ± 35.9 (P = 0.001), fasting leucine levels of 82.9 ± 16.1 vs. 67.4 ± 18.7 (P < 0.001), postprandial leucine levels of 95.3 ± 34.2 vs. 57.7 ± 21.4 (P < 0.001), fasting isoleucine levels of 44.5 ± 9.7 vs. 37.7 ± 13.6 (P = 0.003), and postprandial isoleucine levels of 51.8 ± 19.2 vs. 34.6 ± 28.0 (P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of fasting valine (P = 0.990).

Conclusion: According to the results of our study, fasting and postprandial BCAA levels were found to be higher in the primigravid women with GDM in the low-risk group at 24–28 weeks compared to the control group. These findings suggest that there may be an association between maternal serum BCAA levels and GDM between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus; Branched-chain amino acid; Oral glucose tolerance test

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) describes glucose intolerance that develops or is initially detected during pregnancy. GDM is one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy [1–3]. According to data from the Diabetes Atlas published by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) in 2021, 16.7% of women aged 20–49 who give birth are diagnosed with diabetes. Of these, 80.3% have GDM. According to the results of the Gestational Diabetes Prevalence Study in Turkey (TURGEP) published in 2019, the prevalence of GDM in Turkey is 16.2%. The prevalence of GDM in society is increasing [4]. The main reasons for the increase in prevalence are obesity and advancing maternal age. GDM can lead to complications for both the mother and fetus, occurring in the short and long term. The aim of GDM screening is to make an early diagnosis in order to prevent complications associated with GDM.

In order to screen and diagnose GDM, the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is typically administered between the 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy. However, there is no global consensus on whether GDM screening should be universal or targeted to high-risk individuals, which diagnostic test to use, the cut-off values for interpretation, or whether the screening should be performed in one or two stages. The best practices and diagnostic criteria for GDM remain under discussion. The IADPSG and WHO advocate performing a one-step test, the American Diabetes Association advises a two-step test, and in Turkey, the National Endocrinology and Metabolism Society supports the use of either procedure [5–7].

Amino acids are the basic building blocks of the human body. BCAAs, which include valine, leucine, and isoleucine, are essential amino acids that need to be obtained from outside sources [8]. Consuming the daily required amount of BCAAs helps to regulate blood sugar [9]. Studies have shown a relationship between high plasma BCAA levels and the risk of obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes [10–12]. There are also a few studies that evaluate the relationship between GDM and BCAA levels. However, these studies vary in their populations and results. While some studies indicate elevated plasma BCAA levels in GDM, others report levels within normal ranges [13–17].

The aim of our study was to evaluate the potential role of BCAAs in the diagnosis of GDM by comparing second-trimester serum BCAA concentrations between low-risk primigravid women with and without GDM.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Our study included a total of 110 primigravida (55 pregnant women with GDM and 55 in the control group) who presented to the Antenatal Clinic of Ankara Bilkent City Hospital Women’s Health and Obstetrics Hospital between January and September 2023, during weeks 24–28 of pregnancy. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Health Sciences University (E. Committee study no. E-2-23-3185, 18/01/2023). The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All pregnant women participating in the study were questioned about their demographic characteristics, along with their medical history, presence of accompanying chronic diseases, medications used, history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), current weight, height, body mass index (BMI), pre-pregnancy weight, personal birth weight, and presence of individuals with a history of diabetes mellitus (DM) in the family. In our study, participants were selected from a low-risk group for GDM, as they did not exhibit established risk factors such as BMI ≥ 25, sedentary lifestyle, early pregnancy excessive weight gain, PCOS history, family history of diabetes, certain ethnic backgrounds, prior macrosomic delivery, HbA1c ≥ 5.7%, or diets high in red and processed meats. The study included primigravid women aged 18–40 years, without a family history of DM, without accompanying maternal disease or PCOS, with a BMI < 30, and between weeks 24 and 28 of pregnancy who agreed to undergo an OGTT. Pregnant women diagnosed with GDM based on OGTT results formed the GDM group, while those without GDM diagnosis constituted the control group.

In pregnant women meeting the inclusion criteria for our study, fasting and postprandial venous blood samples were collected within 1 week after the OGTT to measure the levels of BCAAs in serum. Samples for plasma amino acid levels were collected in tubes containing dipotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Becton Dickinson Vacutainer Systems, USA). Subsequently, the venous blood samples were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at Ankara Bilkent City Hospital Medical Biochemistry Laboratory. After appropriate centrifugation, the plasma was separated from the samples, and the levels of amino acids were analyzed. Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry was employed to analyze the concentrations of valine, leucine, and isoleucine (Matography/Mass spectrometry device, Sciex QTrap 4500, Foster City, CA). The samples were analyzed using a commercially available device. In line with the study methodology, plasma amino acids were obtained via acidic extraction and deproteinization. The derivatized amino acids were completely dried by evaporation, reconstituted with appropriate reagents, and analyzed using the LC-MS/MS system. The area corresponding to each standard was used to construct a calibration curve and derive the regression equation.The analyses were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) version 22. Descriptive data in the study were presented as n (%) values for categorical variables, and mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) values for continuous variables. Pearson Chi-square test was used for comparing categorical variables between groups. Normal distribution of continuous variables was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student’s t-test was applied for comparing binary groups in variables showing normal distribution, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for variables not showing normal distribution. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to measure the diagnostic value of amino acids. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in the analyses.

| Results | ▴Top |

A total of 110 women, comprising of 55 with GDM and 55 as controls, were included in the study. The sociodemographic characteristics of the groups are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of those in the GDM group was 28.3 ± 4.3, while it was 27.6 ± 5.3 in the control group, and no significant difference was observed between them (P = 0.49). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of pre-pregnancy weight (P = 0.60), current weight (P = 0.83), height (P = 0.74), and BMI (P = 0.56). The data are summarized in Table 2.

Click to view | Table 1. Comparison of the Sociodemographic Characteristics Between Groups |

Click to view | Table 2. Comparison of the Anthropometric Characteristics Between Groups |

In our study, pregnant women diagnosed with GDM had significantly higher levels compared to the control group in terms of postprandial valine 168.5 ± 46.8 vs. 138.5 ± 35.9 (P = 0.001), fasting leucine 82.9 ± 16.1 vs. 67.4 ± 18.7 (P < 0.001), postprandial leucine 95.3 ± 34.2 vs. 57.7 ± 21.4 (P < 0.001), fasting isoleucine 44.5 ± 9.7 vs. 37.7 ± 13.6 (P = 0.003) and postprandial isoleucine 51.8 ± 19.2 vs. 34.6 ± 28.0 (P < 0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of fasting valine levels (P = 0.990) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Comparison of Fasting and Postprandial Amino Acid Values Between Groups |

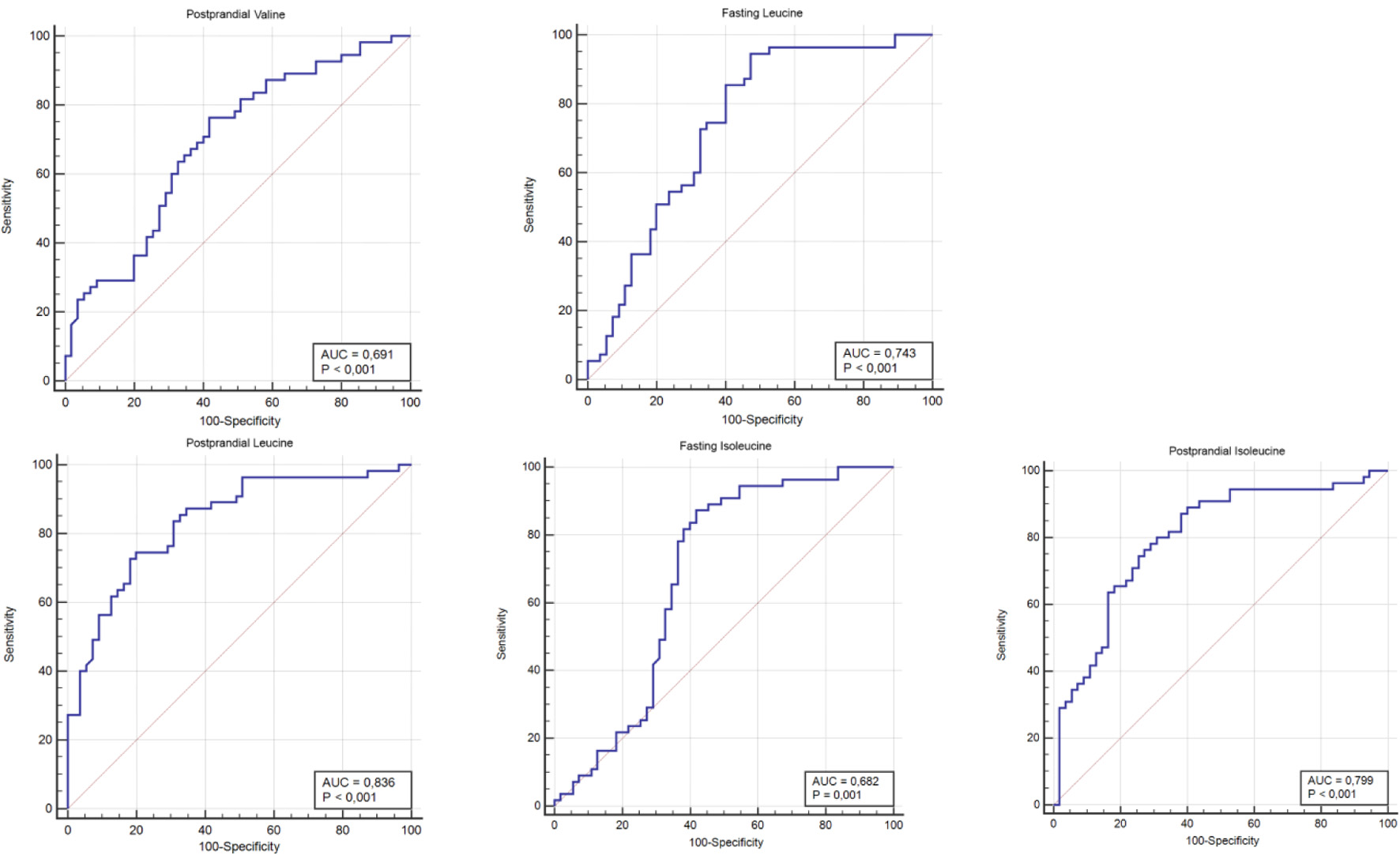

ROC analyses were conducted to calculate the most suitable values for serum BCAA levels that could be used in diagnosing GDM, and cutoff values were determined. When a value of 138.64 µmol/L was taken as the cutoff for postprandial valine, a sensitivity of 76.4% and specificity of 58.2% were observed, indicating that it would be a good determinant. For fasting leucine, a cutoff value of 61.18 µmol/L yielded a sensitivity of 94.5% and specificity of 52.7%, indicating that it would be a good determinant. When a cutoff value of 74.9 µmol/L was taken for postprandial leucine, a sensitivity of 74.5% and specificity of 80% were observed, indicating that it would be the most specific determinant. For fasting isoleucine, a cutoff value of 36.32 µmol/L yielded a sensitivity of 87.3% and specificity of 58.2%, indicating indicating that it would be a good determinant. When a cutoff value of 37.95 µmol/L was taken for postprandial isoleucine, a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 69.1% were observed, indicating that it would be a good determinant (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Click to view | Table 4. Specificity and Sensitivity of Amino Acids in Determining the Diagnosis of GDM |

Click for large image | Figure 1. The ROC curve of postprandial valine, fasting leucine, postprandial leucine, fasting isoleucine, and postprandial isoleucine values for gestational diabetes mellitus. ROC: receiver operating characteristic. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The prevalence of GDM is increasing worldwide. The growing rates of obesity among women, combined with urban sedentary habits and an aging population, suggest that GDM prevalence will continue to rise in the future [18, 19]. As a significant pregnancy complication, GDM can give rise to multiple short- and long-term effects on both the mother and the fetus [3]. Proper screening for GDM, along with early diagnosis and treatment, can help prevent complications.

Currently, screening and diagnosis heavily rely on glucose-based screening tests. Studies investigating the behavior of pregnant women towards these tests have reported an increasing rate of refusal for an OGTT [20–22]. Completing an OGTT depends on the pregnant woman being fasted, ingesting a fixed amount of glucose, spending at least 2 h at the testing facility, and consenting to multiple blood draws [22]. Reasons for test refusal include the perceived difficulty and time-consuming nature of an OGTT by pregnant women, as well as the perception influenced by media reports that it is a harmful and unnecessary procedure, which can delay or hinder the diagnosis of GDM [20–22]. Failure to conduct screening tests increases the rates of undiagnosed GDM-related complications among pregnant women [22].

BCAAs, which are essential amino acids, activate insulin secretion, promote glucose uptake from the blood into cells by preserving glycogen stores in the liver and muscles, and regulate blood glucose levels [23]. The relationship between BCAAs and insulin resistance has been the subject of numerous studies. Studies on dietary supplementation of BCAAs in humans and animals suggest that circulating amino acids may directly increase insulin resistance, possibly through the disruption of insulin signaling in skeletal muscle [10, 24]. BCAAs can trigger insulin resistance through different mechanisms in various tissues. In skeletal muscle, BCAA accumulation increases fatty acid uptake and may lead to incomplete fatty acid oxidation, thereby inducing insulin resistance. Within liver tissue, the breakdown of branched-chain α-keto acids perturbs the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle, triggering mitochondrial stress and insulin resistance [25, 26]. The prolonged elevation of plasma BCAA levels leads to hyperactivation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, resulting in impairment of insulin receptor substrates [27, 28]. While there are studies demonstrating the association of increased BCAA levels with obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes, Wang et al stated that the combination of BCAAs predicts future diabetes [11]. Although type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and GDM share some aspects of pathogenesis, studies evaluating the relationship between GDM and BCAAs are limited.

Although there are studies suggesting that plasma BCAAs can be used as biomarkers for GDM, there are also studies that do not support this role in detecting GDM [13–17]. Cetin et al demonstrated that there was no difference in maternal plasma BCAA concentrations between women with and without GDM during elective cesarean section, as they monitored glucose levels in women with GDM until delivery, regulating them either by diet or diet and insulin [16]. Rahimi et al demonstrated higher fasting plasma valine and isoleucine concentrations in women with T2DM compared to those with and without GDM, although postprandial levels were not studied, and they stated that there was no difference in serum BCAA levels between women with and without GDM in their study [17]. In a study by Roy et al, non-fasting BCAAs, especially leucine, in first-trimester pregnant women, when combined with BMI and a family history of diabetes, could be used to identify women at risk of developing GDM [13]. Hou et al only found significantly higher fasting BCAAs in the GDM group of pregnant women. However, in this study, women with GDM were older and had significantly higher pre-pregnancy BMI compared to the control group [14]. Similarly, Park et al used a two-step screening test and examined BCAA levels after achieving blood sugar regulation with diet, exercise, and/or insulin in women diagnosed with GDM. They stated that the presence of high plasma BCAAs, when combined with other risk factors for GDM, would be useful in identifying women at risk of developing GDM [15]. Plasma BCAA concentrations may vary according to different age groups, BMI groups, and ethnic groups [29]. Additionally, it is known from previous studies that a recently consumed meal affects metabolism and particularly the amino acid profile in circulation [30]. To mitigate the impact of all these factors in our study, fasting and non-fasting BCAA levels were examined in low-risk pregnant women with similar age and BMI who were diagnosed with GDM. Our study is the first to demonstrate elevated levels of fasting and postprandial BCAAs in pregnant women with GDM among homogeneous groups in the Turkish population in the literature we have reviewed so far. The limitations of our study include the small total number of patients and the fact that our study population consisted of pregnant women living in the same region.

Conclusions

As a result of our study, it was found that postprandial valine, fasting leucine, postprandial leucine, fasting isoleucine, and postprandial isoleucine values were significantly higher in pregnant women with GDM compared to the control group. However, no significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of fasting valine values.

These findings suggest that there may be an association between maternal serum BCAA levels and GDM between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. However, our study does not provide sufficient evidence to support the use of BCAAs for the diagnosis of GDM and further prospective, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the validity and feasibility of this method.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of Ankara Bilkent City Hospital for their technical support and assistance in data collection.

Financial Disclosure

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest and funding.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study or their legal guardians or wards.

Author Contributions

Dr. Gizem Sayar and Dr. Raziye Desdicioglu designed the study together. Dr. Gizem Sayar collected the data. Dr. Ceylan Bal and Dr. Gulsen Yilmaz evaluated the laboratory results obtained from the patients. Dr. Gizem Sayar, Dr. Raziye Desdicioglu, and Dr. Elcin Islek Secen performed the statistical analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ, Karuranga S, Piemonte L, Riley P, Saeedi P, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas - 10th Edition [Internet]. 2021 [cited Jan 20, 2024]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resourcefiles/2021/07/IDF_Atlas_10th_Edition_2021.

- Atmaca A, Salman S. Turkiye Endokrinoloji ve Metabolizma Dernegi Diabetes Mellitus ve Komplikasyonlarinin Tani, Tedavi ve Izlem Kilavuzu - 2022 [Internet]. 15th ed. Atmaca A, Salman S, Ozdemir D, Pekkolay Z, Satman I, Adas M, editors. Vol. 1. Ankara: BAYT Bilimsel Arastirmalar Basin Yayin ve Tanitim Ltd. Sti. 2022. p. 322. Available from: https://file.temd.org.tr/Uploads/publications/guides/documents/diabetesmellitus_2022.

- Johns EC, Denison FC, Norman JE, Reynolds RM. Gestational diabetes mellitus: mechanisms, treatment, and complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(11):743-754.

doi pubmed - American Diabetes Association. 2. classification and diagnosis of di abetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:14-31.

- International Association of D, Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel, Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676-682.

doi pubmed - World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycemia first detected in pregnancy; 2013. Available at: https:// apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85975. Accessed Mar 01, 2022.

- Turkey endocrinology and metabolism society study and training group. Diabetes Mellitus, and Complications, Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up Guide. 14th ed. Ankara: TEMD; 2020.

- Vanweert F, Schrauwen P, Phielix E. Role of branched-chain amino acid metabolism in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes-related metabolic disturbances BCAA metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 2022;12(1):35.

doi pubmed - Doi M, Yamaoka I, Nakayama M, Sugahara K, Yoshizawa F. Hypoglycemic effect of isoleucine involves increased muscle glucose uptake and whole body glucose oxidation and decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(6):E1683-1693.

doi pubmed - Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Lien LF, Haqq AM, et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9(4):311-326.

doi pubmed - Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Cheng S, Rhee EP, McCabe E, Lewis GD, et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):448-453.

doi pubmed - Zheng Y, Li Y, Qi Q, Hruby A, Manson JE, Willett WC, Wolpin BM, et al. Cumulative consumption of branched-chain amino acids and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(5):1482-1492.

doi pubmed - Roy C, Tremblay PY, Anassour-Laouan-Sidi E, Lucas M, Forest JC, Giguere Y, Ayotte P. Risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in relation to plasma concentrations of amino acids and acylcarnitines: A nested case-control study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;140:183-190.

doi pubmed - Hou W, Meng X, Zhao A, Zhao W, Pan J, Tang J, Huang Y, et al. Development of multimarker diagnostic models from metabolomics analysis for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Mol Cell Proteomics. 2018;17(3):431-441.

doi pubmed - Park S, Park JY, Lee JH, Kim SH. Plasma levels of lysine, tyrosine, and valine during pregnancy are independent risk factors of insulin resistance and gestational diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2015;13(2):64-70.

doi pubmed - Cetin I, de Santis MS, Taricco E, Radaelli T, Teng C, Ronzoni S, Spada E, et al. Maternal and fetal amino acid concentrations in normal pregnancies and in pregnancies with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(2):610-617.

doi pubmed - Rahimi N, Razi F, Nasli-Esfahani E, Qorbani M, Shirzad N, Larijani B. Amino acid profiling in the gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;16:13.

doi pubmed - Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Risk of Progression to Type 2 Diabetes: a Global Perspective. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16(1):7.

doi pubmed - Seshiah V, Das AK, Balaji V, Joshi SR, Parikh MN, Gupta S, Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group. Gestational diabetes mellitus—guidelines. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:622-628.

pubmed - Ozceylan G, Toprak D. Effects of controversial statements on social media regarding the oral glucose tolerance testing on pregnant women in Turkey. AIMS Public Health. 2020;7(1):20-28.

doi pubmed - Sezer H, Yazici D, Canbaz HB, Gonenli MG, Yerlikaya A, Ata B, Bekdemir B, et al. The frequency of acceptance of oral glucose tolerance test in Turkish pregnant women: A single tertiary center results. North Clin Istanb. 2022;9(2):140-148.

doi pubmed - Lachmann EH, Fox RA, Dennison RA, Usher-Smith JA, Meek CL, Aiken CE. Barriers to completing oral glucose tolerance testing in women at risk of gestational diabetes. Diabet Med. 2020;37(9):1482-1489.

doi pubmed - Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS, Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women Trial Group. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2477-2486.

doi pubmed - Herman MA, She P, Peroni OD, Lynch CJ, Kahn BB. Adipose tissue branched chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism modulates circulating BCAA levels. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(15):11348-11356.

doi pubmed - Newgard CB. Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;15(5):606-614.

doi pubmed - Shou J, Chen PJ, Xiao WH. The effects of BCAAs on ınsulin resistance in athletes. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2019;65(5):383-389.

doi pubmed - Xie J, Herbert TP. The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass: implications in the development of type-2 diabetes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(8):1289-1304.

doi pubmed - Krebs M, Krssak M, Bernroider E, Anderwald C, Brehm A, Meyerspeer M, Nowotny P, et al. Mechanism of amino acid-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes. 2002;51(3):599-605.

doi pubmed - Zhao L, Wang M, Li J, Bi Y, Li M, Yang J. Association of circulating branched-chain amino acids with gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;17(3):e85413.

doi pubmed - Bentley-Lewis R, Huynh J, Xiong G, Lee H, Wenger J, Clish C, Nathan D, et al. Metabolomic profiling in the prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2015;58(6):1329-1332.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.