| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 3, October 2025, pages 100-105

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy or Atypical Presentation of Homolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelets Syndrome: The Dilemma Continues

Samah Ballala, b, Bidisha Ghosha

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, North Manchester General Hospital, Manchester M8 5RB, UK

bCorresponding Author: Samah Ballal, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, North Manchester General Hospital, Manchester M8 5RB, UK

Manuscript submitted August 21, 2025, accepted October 3, 2025, published online October 24, 2025

Short title: AFLP or Atypical HELLP Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo942

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We report a case of a 28-year-old female in her first pregnancy at 31 + 1 weeks gestation who presented with upper abdominal pain and vomiting. Her pregnancy was complicated with gestational diabetes and she was newly started on metformin. On presentation, she complained of abdominal pain and vomiting. She was hypoglycemic, acidotic and bloods revealed hepatorenal failure and coagulopathy. A differential diagnosis of acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP), atypical homolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) or lactic acidosis from metformin was made. The patient was promptly delivered by cesarean section under general anesthetic. The post-delivery course was complicated with an intensive care unit (ICU) stay with worsening hepatorenal function, hypertension, and encephalopathy. A multidisciplinary approach was employed resulting in significant improvement by the 6-week follow-up, with blood parameters nearly normalized. Despite retrospective analysis, clinicians still face a diagnostic dilemma with varying opinions on the definitive diagnosis.

Keywords: HELLP syndrome; Hepatorenal failure; Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

HELLP syndrome is characterized by hemolysis with a microangiopathic blood smear, elevated liver enzymes, and a low platelet count [1]. In 1982, Weinstein subsequently associated HELLP syndrome as a consequence of preeclampsia (PET) [2]. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a rare condition which is characterized by the accumulation of the fat in the liver, leading to liver dysfunction. There is a huge overlap between clinical presentation and biochemical markers associated with HELLP syndrome and AFLP. Both conditions are associated with high maternal morbidity and mortality. Although completely different entities, both conditions require early diagnosis and prompt delivery to achieve the best possible outcome.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

Antenatal

A 28-year-old primigravida of Indian descent booked at 8 weeks gestation at North Manchester General Hospital. She had an uneventful pregnancy up until 31 + 2 where she had a late diagnosis of gestational diabetes and was started on metformin. A subsequent growth scan revealed normal liquor volume, Doppler and growth was just below 90th centile (1,882 g at 32 + 1).

Presentation

She presented to maternity triage at 35 weeks 3 days, with a 1-week history of constant upper abdominal pain and vomiting. On presentation, her blood pressure (BP) was 132/77 mm Hg, heart rate was 100 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 bpm, 100% saturation on room air, and a temperature of 36.3 °C. Her urine was dark and concentrated and had a plus of protein.

Diagnosis

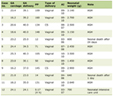

On examination, abdomen was soft nontender and she had no per vaginal loss. It was also noted that she had pitting edema to her ankles. Routine blood test (full blood count (FBC)/urea and electrolytes (U&E)/liver function test (LFT)/C-reactive protein (CRP)), PET markers, and a urine polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were sent to the lab (Table 1). Dawes-Redman cardiotocography (CTG) did not meet the criteria due to few accelerations. CTG otherwise appeared normal.

Click to view | Table 1. Blood Test at Initial Presentation |

Her blood sugars were done due to persistent vomiting and history of gestational diabetes. It was found to be 3.2 mmol. She was given a glucose shot and 15 min later blood sugar was still 3.2 mmol. Another glucose shot was administered, and BM dropped to 3.1 mmol. Blood results revealed hepatorenal failure with low platelets.

It was also noted that she may have appeared slightly jaundiced. A blood gas showed that the patient was in metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.25, HCO3 17.5, base excess (BE) -9.7, lactate 2.3, and K 4.0.

Our provisional diagnosis was: 1) AFLP; 2) HELLP syndrome secondary to severe PET; and 3) lactic acidosis secondary to metformin.

Treatment

After a multidisciplinary discussion including two obstetric consultants, an anesthetic consultant, intensive care unit (ICU) registrar and medical registrar, delivery by immediate cesarean section under general anesthetic was decided as there was no clotting result available.

She was given a dose of 12 mg intramuscular dexamethasone for fetal lung maturation. Cesarean section was straight forward and total blood loss was 650 mL.

A baby girl weighing 2,330 g was delivered with appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration (APGAR) score of 9, 9, and 10 at 1, 5, and 10 min, respectively.

Cord gases in baby showed an arterial pH of 7.22, BE -6, and a venous pH of 7.23 and BE -8.3 and baby was clinically well.

Maternal clotting results came back as deranged (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Maternal Clotting Results |

A repeat venous gases showed worsening acidosis with a pH 7.24, HCO3 10, and lactate 3.0. She was transferred to ICU and was successfully extubated 12 h later. One hour post-operation, she was bleeding from her wound and was therefore given 1 unit of platelets and a pool of cryoprecipitate.

Follow-up and outcomes

Post-delivery the liver transplant unit at Leeds General Infirmary was contacted and they advised preparations to be made for a liver transplant if she was not responding to treatment.

She had a total of 9 days in ICU stay where she required: 1) red blood cell (RBC)/platelet and cryoprecipitate transfusions; 2) continuous positive airway pressure therapy; 3) dextrose infusion with actrapid to maintain blood sugars; 4) labetalol and later amlodipine for BP control as she was then hypertensive with proteinuria (urine protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR) 59); 5) multiple episodes of hemodialysis as she was showing features of acute renal failure with worsening urea and creatinine, pulmonary and pedal edema; 6) lactulose and rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy as she was becoming increasingly confused with raised ammonia.

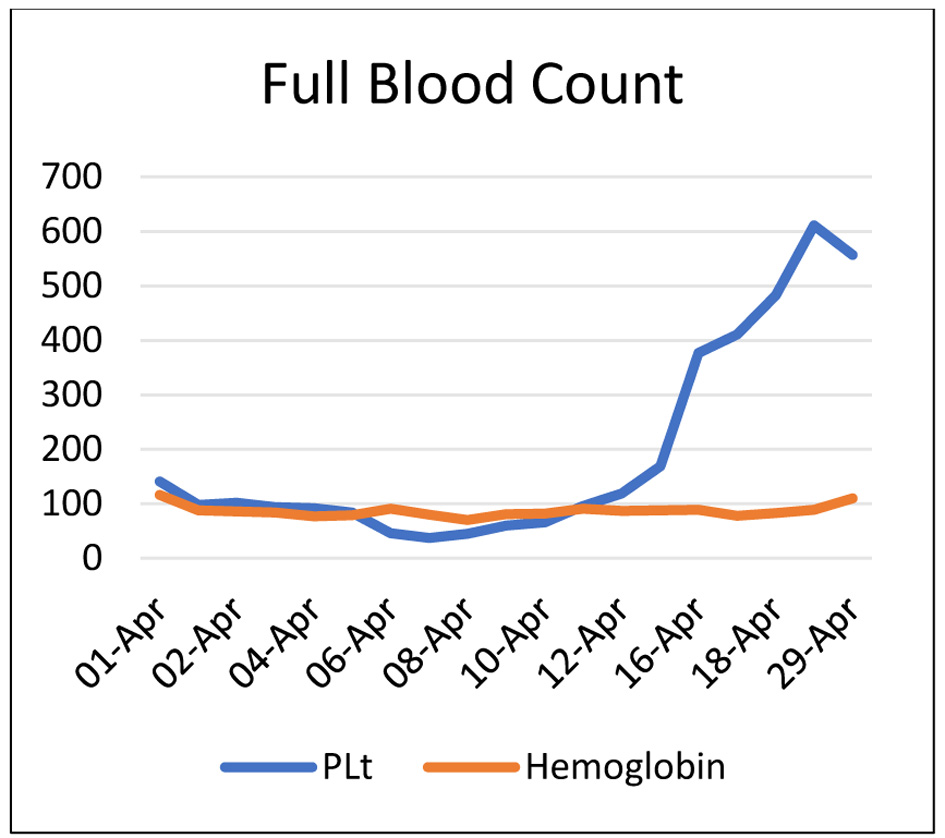

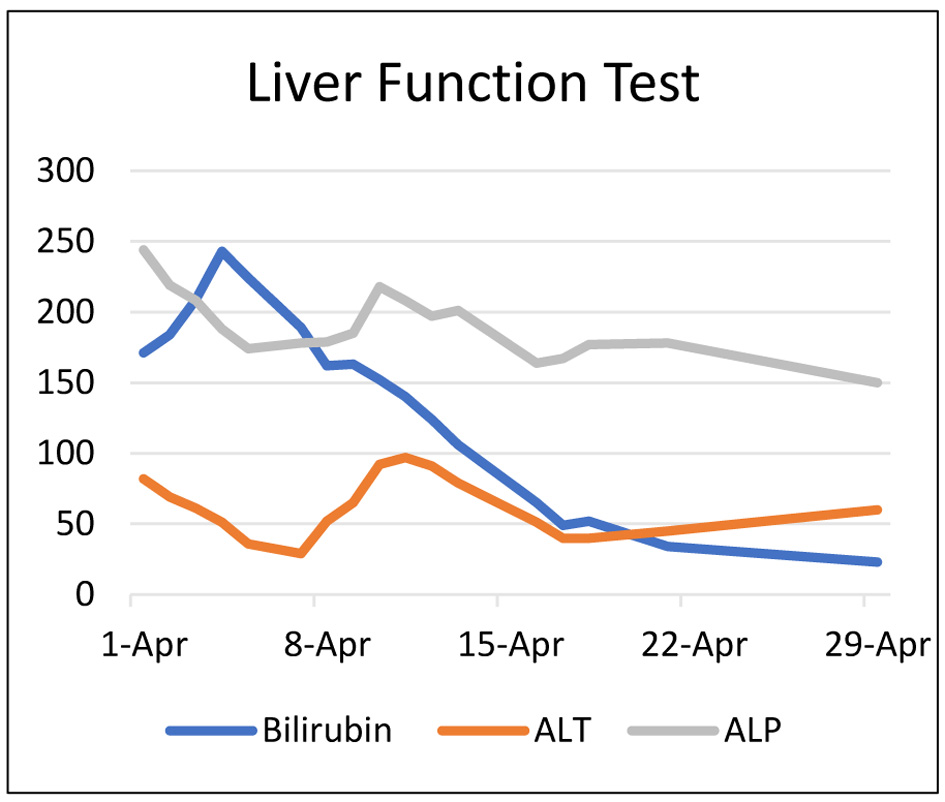

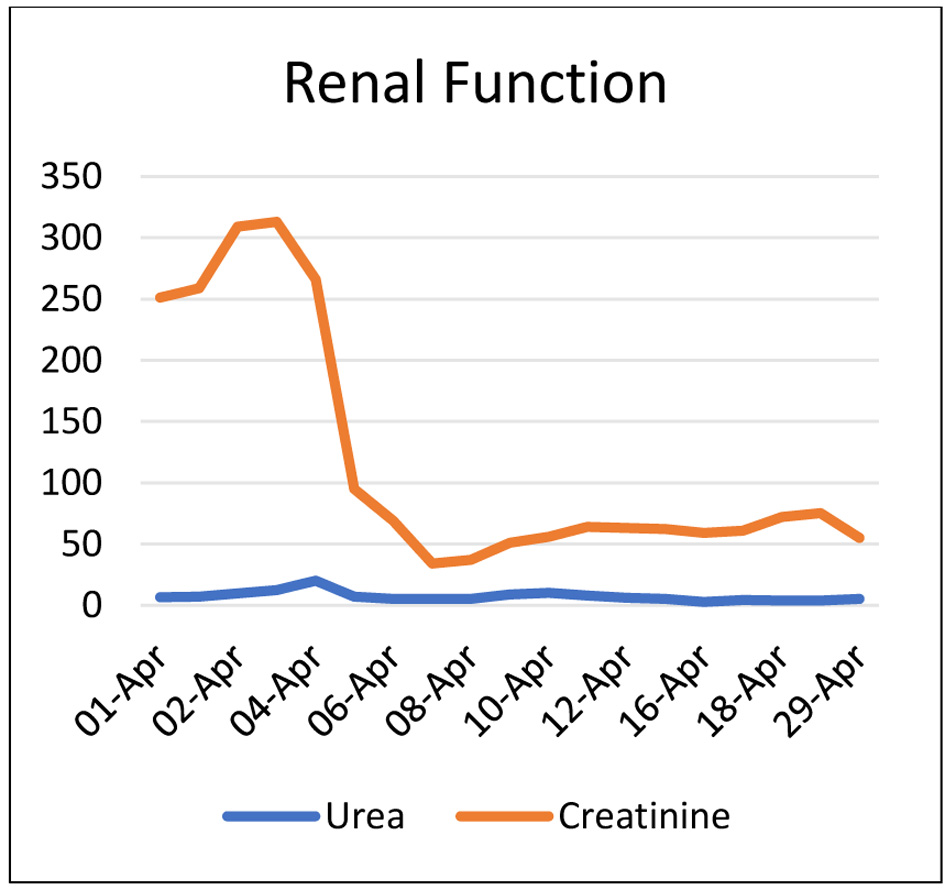

Ultrasound (USS) scan of the liver and urinary system was unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis also showed normal liver and portal veins. Large bilateral pleural effusions and abdominal wall edema were noted indicating fluid retention. Liver biopsy was not done due to risk of bleeding from the coagulopathy. The patient had daily bloods which showed marked improvement. Prior to discharge, clotting normalized and noninvasive liver screen was normal. She was followed up 6 weeks postnatally and FBC/U&E/LFT were normal except she had a mildly raised alanine transaminase (ALT) at 66 IU/L (Figs. 1-3). Further blood results during her stay revealed low serum haptoglobin, raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and conjugated bilirubin indicating hepatocellular damage (Table 3).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Full blood count. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Liver function test. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Renal function test. |

Click to view | Table 3. Further Blood Results |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

HELLP syndrome was first described by Pritchard in 1954. It is characterized by hemolysis with a microangiopathic blood smear, elevated liver enzymes, and a low platelet count [1].

In 1982, Weinstein subsequently associated HELLP syndrome as a consequence of PET [2]. Although 15-20% of patients with HELLP do not have associated hypertension or proteinuria [3]. Overall HELLP develops in 0.2-0.8% of pregnancies [2, 3].

Presentation with HELLP syndrome can vary but the onset of symptoms is usually rapid and progressively worsens. HELLP often develops between 28 and 37 weeks of gestation. However, symptoms can develop late in the second trimester, or even at 40 weeks. In some cases, it has developed even in the postpartum period.

Patients typically present with abdominal pain, general malaise, nausea, and vomiting. The pain is often epigastric or right upper quadrant.

Less commonly, the patients present with headaches, visual disturbances, jaundice, and ascites [4].

The diagnostic criteria for HELLP syndrome are variable and inconsistent.

Some studies suggest the use of the Tennessee classification as illustrated in the Table 4 [5]. Based on the Tennessee classification, our case fits the criteria for HELLP syndrome. Her initial platelet count was 141 but later dropped to 37 at its lowest despite platelet transfusion. She was diagnosed with PET on the basis of raised UPCR and raised BP requiring antihypertensives. However, the raised BP presented later during her admission. Together with the diagnosis of PET, it fits the clinical picture that the resultant presentation and biochemical change was secondary to HELLP syndrome, based on Weinstiein’s definition.

Click to view | Table 4. Tennessee Classification for the Diagnosis of HELLP Syndrome According to Ditisheim et al [5] |

HELLP syndrome has a wide differential diagnosis as illustrated in Table 5. Baha discussed this in an article and further illustrated the diagnostic complexity that comes with HELLP [6].

Click to view | Table 5. Differential Diagnosis in Women With HELLP Syndrome According to Baha [6] |

In this case, there was discussion regarding whether this patient had HELLP syndrome or AFLP. This is because there is a strong overlap in the clinical presentation and biochemical makers between HELLP syndrome and AFLP [7]. The remainder of this case focuses on these two phenomena following multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach including ICU/anesthetic colleagues, local liver unit, and medical team, and it was concluded that this was the most likely cause of her presentation.

Both conditions are life-threatening with high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality. Although completely different, both conditions require early diagnosis and prompt termination of pregnancy, to achieve the best possible outcome for both mother and baby. The maternal mortality rate associated with HELLP syndrome is 1-24% and maternal mortality rate associated with AFLP is as high as 80% [8].

AFLP was first described by Sheehan in 1940. His findings were based on liver histology from autopsies [9]. AFLP is extremely rare and has an incidence of 7,000 to 20,000 pregnancies [10].

Hypertension is not as common in AFLP as HELLP syndrome and ranges from 26% to 70%. AFLP patients generally present with vague symptoms, hence this creates some diagnostic delay. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and anorexia. However, patients may also quickly develop the manifestations that are associated with AFLP. Within 24 h of presentation, AFLP manifestations were evident in our patient’s state. She had acute liver failure with jaundice, encephalopathy, acute renal failure, coagulopathy, and hypoglycemia.

The Swansea criteria can be used as a diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of AFLP. Positive diagnosis is based on 6 - 9 features in women with HELLP as illustrated in Table 6 [11].

Click to view | Table 6. Swansea Criteria for the Diagnosis of AFLP [11] |

Hypoglycemia occurs more frequently in AFLP. However, our patient had gestational diabetes and presented with vomiting. Although she was not on insulin, occasionally, hormonal changes can cause women with diabetes to develop hypoglycemia even without medication.

Liver biopsy is included in the Swansea criteria; however, this is rarely needed to diagnose AFLP and is only reserved for patients where there is diagnostic doubt and results will affect the patient’s future management [12].

Our patient had fulfilled nine criteria from Table 6, which guides to a diagnosis of AFLP. This leads to the question of “how accurate is the Swansea criteria?”

In 2020, a study was conducted in Denmark by Rahim et al [13]. They found that out of 29 patients with AFLP, all 29 fulfilled the Swansea criteria with a score ≥ 6. While the patients who had HELLP, 11/30 fulfilled the Swansea criteria. Therefore, the Swansea criteria have 100% sensitivity but only 63% specificity.

Rahim et al therefore concluded that “The Swansea criteria need to be modified to allow better distinction between HELLP and AFLP in a clinical setting” [13].

Interestingly, antithrombin activity may play a role in helping differentiate between HELLP and AFLP. Antithrombin is a protein produced by the liver which is involved in the coagulation cascade. In liver dysfunction, this protein is deficient, hence reduced activity of less than 65% may add more evidence that points to AFLP. This test however, was not done for our patient, therefore we cannot say for definite what was the diagnosis in her case.

Overall management of both HELLP and AFLP in this case was the same. Prompt delivery of the baby was conducted to reduce the perinatal and maternal mortality rate.

As previously mentioned, delivery is necessary for both AFLP and HELLP syndrome.

There is no definite advice that cesarean section is the chosen mode of delivery for AFLP but studies do suggest that it is the preferred method. Statistics in a small study by Wei et al in 2010 illustrated why this is the case. The maternal mortality rate with cesarean section is 16% as compared to 48.1% with normal vaginal delivery (NVD). In addition, the perinatal mortality rate with NVD was more than double (26.5%) the rate with cesarean section (10.6%) [14].

It is also worth mentioning that magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) plays an immense role in seizure prevention in severe PET/HELLP syndrome. It was not started in this case as it was initially felt that AFLP was the likely diagnosis.

Learning points

The case reinforces the critical role of timely delivery in improving maternal and perinatal outcomes. The choice of delivery method, such as cesarean section, aligns with the necessity for swift action to address the life-threatening nature of AFLP and HELLP syndrome. Collaborative decision-making is crucial in ensuring prompt and effective interventions. The diagnostic criteria for both AFLP and HELLP syndrome still necessitate modification, as their sensitivity remains high but specificity is lacking. The discussion on antithrombin activity highlights the potential role of additional diagnostic tests in distinguishing between AFLP and HELLP syndrome. This suggests that in challenging situations, clinicians should consider a comprehensive diagnostic approach, potentially including tests beyond standard criteria, to enhance accuracy.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Author Contributions

Both authors analyzed the diagnosis and the management of the case, and they edited and approved the last version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this case report are available within the article.

Abbreviations

AFLP: acute fatty liver of pregnancy; APGAR: appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; CTG: cardiotocography; FBC: full blood count; HELLP: homolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets; ICU: intensive care unit; LFT: liver function test; MDT: multidisciplinary team; MgSO4: magnesium sulphate; NVD: normal vaginal delivery; PET: preeclampsia; RBC: red blood cells; U&E: urea and electrolytes; UPCR: urine protein-creatinine ratio; USS: ultrasound

| References | ▴Top |

- Pritchard JA, Weisman R, Jr., Ratnoff OD, Vosburgh GJ. Intravascular hemolysis, thrombocytopenia and other hematologic abnormalities associated with severe toxemia of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1954;250(3):89-98.

doi pubmed - Weinstein L. Syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count: a severe consequence of hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142(2):159-167.

doi pubmed - Sibai BM, Taslimi MM, el-Nazer A, Amon E, Mabie BC, Ryan GM. Maternal-perinatal outcome associated with the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets in severe preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155(3):501-509.

doi pubmed - Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, Salama M, Mercer BM, Friedman SA. Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(4):1000-1006.

doi pubmed - Ditisheim A, Sibai BM. Diagnosis and Management of HELLP Syndrome Complicated by Liver Hematoma. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(1):190-197.

doi pubmed - Sibai BM. Diagnosis, controversies, and management of the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5 Pt 1):981-991.

doi pubmed - Minakami H, Morikawa M, Yamada T, Yamada T, Akaishi R, Nishida R. Differentiation of acute fatty liver of pregnancy from syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet counts. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(3):641-649.

doi pubmed - Pokharel SM, Chattopadhyay SK, Jaiswal R, Shakya P. HELLP syndrome—a pregnancy disorder with poor prognosis. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10(4):260-263.

pubmed - Sheehan HL. The pathology of acute yellow atrophy and delayed chloroform poisoning. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1940;47:49-62.

- Castro MA, Fassett MJ, Reynolds TB, Shaw KJ, Goodwin TM. Reversible peripartum liver failure: a new perspective on the diagnosis, treatment, and cause of acute fatty liver of pregnancy, based on 28 consecutive cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(2):389-395.

doi pubmed - Knight M, Nelson-Piercy C, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P, System UKOS. A prospective national study of acute fatty liver of pregnancy in the UK. Gut. 2008;57(7):951-956.

doi pubmed - Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G, Williamson C. Pregnancy and liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(4):933-945.

doi pubmed - Mussarat Rahim Emmanouil Kountouris NickKametas Michael Heneghan. SAT259 - Validating the criteria in a single-centre study with cohorts of patients with acute fatty liver of pregnancy and haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome: is it time to modify the criteria? Journal of Hepatology. 2020;73(Supplement 1):S782-S783.

- Wei Q, Zhang L, Liu X. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a literature review and 11 new cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(4):751-756.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.