| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Review

Volume 14, Number 4, December 2025, pages 113-121

Microbiome Dysbiosis in Lichen Sclerosus: A Systematic Review

Sydney K. Rismana, c, Una Milovanovica, Derek S. Weimera, Tanya Ramadossa, Michelle L. Demoryb, c

aDr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

bDepartment of Medical Education, Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

cCorresponding Authors: Michelle L. Demory, Department of Medical Education, Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33328, USA; Sydney Risman, Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33328, USA

Manuscript submitted September 20, 2025, accepted November 5, 2025, published online December 11, 2025

Short title: Microbiome and Lichen Sclerosus

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1555

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition primarily affecting the vulvar and perineal areas, often causing pain, pruritus, and scarring. While vulvar and vaginal microbiome composition is understood to contribute to genital health, their relationship with LS pathogenesis is unclear. Recent studies also suggest that gut microbiome imbalances may influence LS via systemic immune modulation. This systematic review aimed to characterize microbial alterations in the vulvar, vaginal, and gut microbiomes of LS patients and explore potential mechanisms linking dysbiosis to disease progression.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted using five databases: EMBASE, Medline via Ovid, Web of Science, PubMed, and CINAHL. Eligible studies included female patients diagnosed with LS and assessed the primary outcome of vulvar and vaginal microbiome composition. Gut microbiome data were considered a secondary outcome of interest. Following an initial double-blind screening, eight full-text articles were reviewed in the secondary screening, and seven articles were ultimately included in this review.

Results: Seven studies met the inclusion criteria. Across the vulvar, vaginal, and gut microbiomes, consistent patterns emerged, including reductions in protective taxa, such as Firmicutes and Lactobacillus, and increases in pro-inflammatory microbes, including Proteobacteria. Vulvar samples also showed higher abundances of Enterobacteriaceae, Peptoniphilus, and Campylobacter. Gut microbiome alterations included reduced short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, such as Firmicutes and Bacteroides, in addition to elevated Proteobacteria and Rikenellaceae. Alpha diversity findings were variable, and species-level changes were often inconsistent.

Conclusions: Microbial dysbiosis of the vulvar, vaginal, and gut microbiomes may contribute to the development of LS through chronic inflammation, compromised epithelial barriers, and disrupted immune function. While some alterations in the microbiomes were identified, discrepancies between the results of these studies highlight the need for larger, standardized studies to better understand the relationship between the microbiome and LS pathophysiology.

Keywords: Lichen sclerosus; Vulvar microbiome; Vaginal microbiome; Gut microbiome; Microbiome dysbiosis; Proteobacteria; Lactobacillus; Firmicutes

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder predominantly affecting the vulvar and perianal regions. It most commonly presents in postmenopausal women, although it can also affect premenarchal girls and, more rarely, men. LS is characterized by hypopigmentation, atrophic diffuse patches, intense pruritus, and dysmorphic scarring. Progression often leads to architectural changes, such as narrowing of the vaginal opening and fusion of the labial folds [1]. These morphological changes lead to discomfort, dyspareunia, and even psychological distress, greatly impacting the quality of life of those affected [2]. LS also increases the risk of vulvar invasive carcinoma via the differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) pathway, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and long-term management [3, 4]. While the exact etiology of this disease is unclear, LS is believed to be autoimmune-related, with contributions from genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors [2, 3]. High-potency topical corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for symptom control and scar prevention, and long-term maintenance therapy is necessary to reduce the risk of developing vulvar invasive carcinoma [4, 5].

The composition of the vulvar and vaginal microbiome significantly influences urogenital health [6]. The vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus species, which maintain a low vaginal pH (< 4.5) that can prevent pathogen overgrowth and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [7]. Dysbiosis with anaerobes like Prevotella and Gardnerella increases the risk of infections and obstetric complications [8]. Although less extensively studied than the vaginal microbiome, the vulvar microbiome is also essential for genital health. Influenced by vaginal, anal, and skin microbes, a healthy vulvar microbiome is primarily composed of Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium species [9]. Unlike healthy tissue, in LS microbial dysbiosis is often characterized by a reduction in protective bacteria and an increase in inflammatory microbes, such as Prevotella, Peptoniphilus, and Streptococcus [10]. Viral infections, particularly human papillomavirus, have also been detected in LS lesions, complicating its pathogenesis [9]. Emerging evidence indicates that even gut microbiome dysbiosis may influence LS progression through systemic immune modulation [11]. Dysregulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome has been implicated in a range of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, highlighting the potential for concomitant autoimmune conditions [12].

Despite growing recognition of the microbiome’s role in genital health, there is limited research on the relationship between microbiome dysbiosis and LS. Existing studies suggest significant alterations in vaginal, vulvar, and gut microbiomes in LS, but the specific taxa involved and their impact are poorly understood. This review aims to explore microbiome dysbiosis in patients with LS. Furthermore, it seeks to characterize the specific microbial alterations associated with the disease and identify potential mechanisms linking these changes to disease progression, with the goal of informing new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to ensure a meticulous study selection (Table 1). Studies included in the review involved female patients of any age diagnosed with LS, either clinically or via biopsy. Eligible studies were required to focus on the primary outcome of interest: vulvar skin or vaginal microbiome composition in the setting of LS. Information regarding the gut microbiome composition was collected only as a secondary outcome of interest. Acceptable study designs included primary literature, such as retrospective chart reviews, cohort studies, case-control studies, case series, and cross-sectional studies, all published in English. Excluded studies were those published prior to 2000, those with fewer than five participants, and certain study designs, such as case reports, review articles, editorials, research protocols, and animal studies.

Click to view | Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria |

Search strategy

The population, concept, and context strategy was used to guide the research question: “Do the vulvar skin and vaginal microbiomes differ in patients with LS?” The population was patients with LS, the concept was vulvar and vaginal microbiome composition, and the context was studies published after 2000.

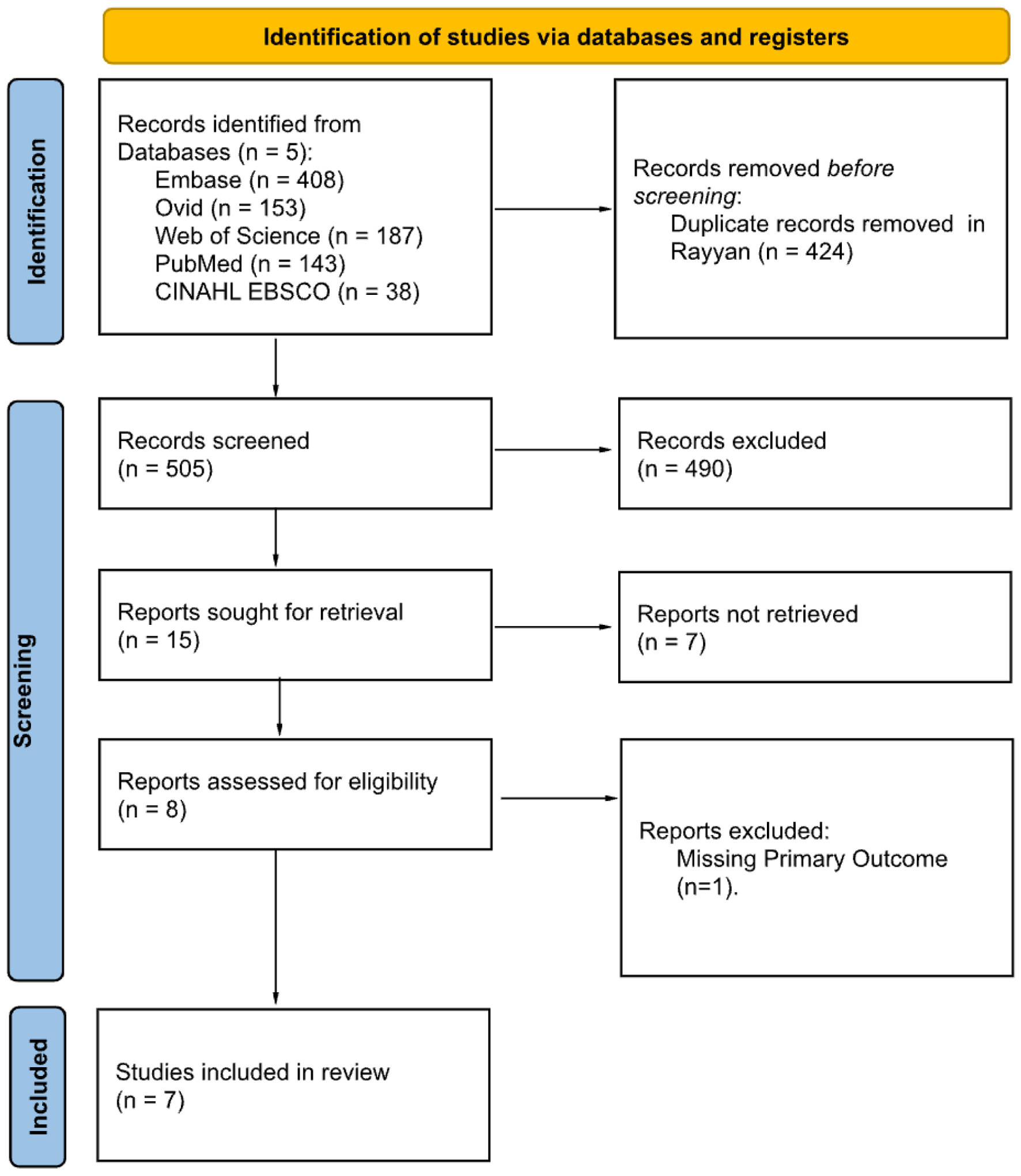

Search terms were developed by one of the authors (SR) and reviewed by another author (DB) (Supplementary Material 1, jcgo.elmerpub.com). Author SR conducted searches in EMBASE, Medline via Ovid, Web of Science, PubMed, and CINAHL, on April 14, 2024. Additionally, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method, as illustrated in Figure 1 [13], was employed to track the progress of our search.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram. Adapted from Ref [13]. |

Study selection, data appraisal

A comprehensive search across five databases initially retrieved 929 articles. An automated search for duplicates in Rayyan [14] eliminated 424 articles, resulting in 505 studies included in the primary screen. Researchers SR and TR independently conducted the initial, double-blind screening of titles and abstracts using the criteria in Table 1. Of the 505 articles screened, 490 articles were excluded. Of the 15 remaining articles, eight were retrievable for full-text review in the secondary screening process. In the secondary screening, SR, TR, and UM carried out a thorough review of all full texts, and seven articles remained. Screening results, including the PRISMA diagram, are displayed in Figure 1.

The seven articles were strictly assessed for quality and bias using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tool checklist for case-control studies, which can be seen in Supplementary Materials 2 and 3 (jcgo.elmerpub.com). Each article was independently evaluated by SR and TR, and any discrepancies in scoring were discussed and resolved. Articles were included if they achieved a mean score exceeding 70% on JBI checklists. All seven articles met this threshold and were thus included in the study. A data-charting form was developed by SR to extract key variables. Data extraction was performed by SR and reviewed for accuracy and completeness by DB.

As this study is a systematic review of previously published data, institutional review board approval was not required. No new studies with human or animal participants were conducted. All included studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of their respective institutions as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

| Results | ▴Top |

Search results

A systematic search of the available literature was completed using five electronic databases: EMBASE, Medline via Ovid, Web of Science, PubMed, and CINAHL. Figure 1 outlines the PRISMA flow diagram with designated reasons for study exclusion. In total, 505 articles were included in the primary screen, and 15 articles remained. The full texts for eight of these articles were included in the secondary screen, and seven articles underwent data collection and analysis.

Vulvar microbiome

Five studies compared the vulvar skin microbiome of LS patients with healthy controls, as shown in Table 2 [9-11, 15, 16]. Liu et al (2022) and Chattopadyay et al (2021) described a higher abundance of bacterial taxa, while Pagan et al (2023) reported an increased abundance of viral taxa in the LS patients’ vulvar microbiome. Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria were dominant phyla in both groups, though relative abundances varied. Three studies found Firmicutes to be less prevalent in LS [10, 15, 16]. Proteobacteria was also identified as a dominant bacterial phylum [15]. A higher relative abundance of both Gammaproteobacteria and Clostridia classes in LS females (linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score > 4) was reported by Liu et al (2022), along with a lower abundance of the order Lactobacillales and family Lactobacillaceae (LDA score > 4). The family Enterobacteriaceae was also noted to be significantly increased in the LS patient group [10]. Similarly, Ma et al (2024) found a significantly higher abundance of Enterobacter cloacae in LS. Only Pagan et al (2023) examined the virome of the vulva, finding increased Papillomaviridae in LS patients (P = 0.045).

Click to view | Table 2. Differences in Vulvar Skin Microbiome of Patients With and Without Lichen Sclerosus |

There was no consensus regarding the abundance of the genus Prevotella: Ma et al (2024) and Pagan et al (2023) reported a lower prevalence, Chattopadhyay et al (2021) noted a higher prevalence, and Liu et al (2022) indicated that there was no significant difference between LS and healthy controls. Peptoniphilus and Campylobacter genera were significantly more prevalent in LS patients [10, 15]. When investigating Lactobacillus prevalence in the vulvar microbiome, Liu et al (2022) described a lower abundance at the labia majora (P < 0.0001), and Pyle et al (2024) found lower levels at the clitoris (P = 0.006). While Liu et al (2022) described an overall decrease in Lactobacillus species, Lactobacillus jensenii was noted to be enriched (LDA score > 4) and Lactobacillus iners was depleted (LDA score > 4). Pyle et al (2024), however, reported that Lactobacillus jensenii decreased at the perineum (P = 0.003). Atopobium was decreased in LS at multiple sites, while Porphyromonas was elevated in two studies [10, 16]. Campylobacter ureolyticus was reported to be more prevalent in LS patients by both Ma et al (2024) and Liu et al (2022). Only Pyle et al (2024) studied the fungal composition of the vulvar microbiome, reporting a higher abundance of Candida at the labia minora (P < 0.001), but decreased prevalence of Candida glabrata at several sites.

Alpha diversity indices were inconsistent. Three of the five studies described at least one metric indicating loss of diversity in LS [9, 10, 16]. Two studies observed decreased species richness [10, 16]. Additionally, two articles described a decreased overall species diversity [9, 16]. Only Liu et al (2022) assessed species evenness, finding no significant differences.

Vaginal microbiome

The vaginal microbiome was investigated in four studies (Table 3) [11, 16-18]. Ma et al (2024) found significantly lower Fusobacteriota and Fusobacteria in the LS vaginal microbiome, with Bifidobacteriaceae dominant in LS and Prevotellaceae dominant in healthy controls. One study identified regional differences in vaginal microbiota and found Streptococcaceae to be more abundant in the upper vagina but not in the lower vagina [18]. Brunner et al (2021) identified two microbiome clusters in both groups: Lactobacillus-dominant and polymicrobial, with the latter primarily containing Gardnerella, Bifidobacterium, and Atopobium. Another study found Atopobium dominant in the upper vagina and Bifidobacterium in the lower vagina [18].

Click to view | Table 3. Differences in Vaginal Microbiome of Patients With and Without Lichen Sclerosus |

The reported genus-level composition varied between the four studies. Streptococcus was dominant in healthy controls but not LS patients [11, 17]. Nygaard et al (2023), however, observed a significantly higher relative abundance of Streptococcus in the lower vagina of women with LS. Three studies found no variation in the relative abundance of Lactobacillus [11, 17, 18]. Pyle et al (2024) primarily focused on fungal microbiome composition, reporting significantly higher Saccharomyces and Candida in LS.

At the species level, Ma et al (2024) noted five species to be increased in LS, including Lactobacillus crispatus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus UMNBX11, and Sphingomonas sp. 3F27F9 (P < 0.05 for all five species). This study also reported that 42 individual species were less prevalent in LS patients, including seven Prevotella species. Brunner et al (2021) reported a higher relative abundance of Lactobacillus iners (P = 0.027), but no significant difference in Streptococcus anginosus (P = 0.832) prevalence. Only Ma et al (2024) recorded measures of alpha diversity, finding significantly lower diversity, richness, and observed species counts (abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE), Chao1, and Observed richness) in LS patients.

Gut microbiome

Although the gut microbiome was not a primary focus, several key findings were found and are displayed in Table 4 [11, 15, 18]. Chattopadhyay et al (2021) identified Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria as dominant phyla in LS patients and healthy controls. Although dominant in both groups, the relative abundance of Firmicutes was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in LS patients’ gastrointestinal microbiome, whereas Proteobacteria abundance was significantly higher (P < 0.05) [15]. Conversely, Nygaard et al (2023) noted a greater prevalence of Euryarchaeota in LS patients (P < 0.05). At the class level, Gammaproteobacteria and Coriobacteriia were reported to be elevated in LS patients by Ma et al (2023) and Nygaard et al (2023), respectively. Coriobacteriales and Clostridiales orders were also enriched in the stool samples of LS patients [15]. At more specific taxonomic levels, the Rikenellaceae family was consistently more prevalent in LS and uniquely dominant only in this group; however, this finding was not statistically significant in the study by Ma et al (2024) [11, 15]. Both Bacteroidaceae and Bacteroides are dominant in the LS and healthy patient groups but significantly lower in the gastrointestinal microbiome of LS patients [11, 18].

Click to view | Table 4. Differences in Gut Microbiome of Patients With and Without Lichen Sclerosus |

Two studies reported higher alpha diversity, defined as species diversity within a community, in LS gut microbiomes [11, 15]. Ma et al (2024) reported that all three metrics of alpha diversity, including ACE, Chao1, and observed (obs) richness, were significantly higher for patients with LS (P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.01). A higher Shannon diversity index in the LS group was observed by Chattopadhyay et al (2021). Conversely, Nygaard et al (2023) observed no difference between the two groups in terms of alpha diversity via three tests: ASV richness (P = 0.059), Shannon diversity index (P = 0.276), and Pielou’s evenness (P = 0.609).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Main findings

This systematic review reveals significant variations in the vulvar, vaginal, and gut microbiomes between patients with LS and healthy individuals. Considering the seven studies included in this review, LS was found to be associated with alterations in bacterial, viral, and fungal communities within the vulvar, vaginal, and gut microbiomes. These findings suggest that microbiome dysbiosis may either contribute to the development of LS or arise as a consequence of disease progression. Because many of the predominant microbial taxa identified are known to influence immune responses, it seems probable that the microbiome contributes to LS pathogenesis. However, inconsistencies across studies highlight the need for additional larger studies to better clarify these relationships.

Vulvar microbiome

Of the three microbiomes investigated, the vulvar microbiome was the most frequently studied. Several trends were observed. Three of the studies reported a reduction in Firmicutes, which may have an impact on immune function [10, 15, 16]. Firmicutes produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which support anti-inflammatory signaling and maintain mucosal integrity. Therefore, a lower abundance of Firmicutes can contribute to local inflammation and increased susceptibility to tissue injury [19, 20]. There were also alterations in the abundance of Lactobacillus, which plays a key protective probiotic role in the genitourinary microbiome. Lactobacillus iners was depleted [10], while Lactobacillus jensenii had variable abundance across all sampled vulvar sites [10, 16]. These alterations can compromise mucosal protection, promote dysbiosis, and facilitate colonization by opportunistic pathogens, suggesting that these microbial alterations may have an impact on LS pathogenesis.

The vulvar swabs of patients with LS also revealed an increased prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae, Campylobacter, and Peptoniphilus; all of these opportunistic bacteria promote local inflammatory responses [10, 11, 15]. Reduced abundance of Atopobium likely reflects a broader microbial imbalance, contributing to increased susceptibility to inflammation and subsequent tissue damage [10, 16]. Conversely, Porphyromonas is increased in abundance [10, 16]. This gram-negative bacterium has an inflammatory effect and promotes extracellular matrix degradation through protease secretion, induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and immune system evasion [21]. Fungal microbiome alterations were only mentioned in one study, which noted an elevation in the prevalence of Candida at the labia minora [16]. Three of the five studies described reduced species richness and overall diversity in the vulvar microbiome of patients with LS [9, 10, 16]. This finding could reflect the loss of protective taxa and may increase susceptibility to inflammation and further tissue damage. Of note, microbial composition may also vary across different vulvar sites. Pyle et al (2024) was the only study to compare the vulvar microbiome across multiple locations. Although the authors did not definitively report how the microbiome differs between sites in the context of vulvar lichen sclerosus (VLS) versus healthy controls, they suggested that factors such as skin type, moisture, and proximity to the anus may influence site-specific microbial composition.

Vaginal microbiome

The vaginal microbiome findings were less consistent. Although overall Lactobacillus abundance was not significantly changed, species-level shifts were reported. Lactobacillus iners, a known pathogenic bacterium, was found to be increased [17]. This species expresses virulence factors, such as inerolysin and AB-1 adhesins, that can disrupt epithelial barriers, induce local inflammation, and reduce immune protection against other pathogenic bacteria [22, 23]. Additionally, Bifidobacterium appears to be more dominant in patients with LS [11, 18]. The clinical significance of this finding remains unclear; this change may either contribute to dysbiosis or be a response to the microbial imbalance. Other pathogenic taxa had inconsistent reports on their relative abundances. Multiple Prevotella species were noted by Ma et al (2024) to be reduced in abundance. Prevotella species secrete proteases and inhibit complement, resulting in immune evasion and inflammation [24, 25].

Fungal taxa, including Candida and Saccharomyces, were observed to be elevated in LS. These microbes may potentially exacerbate pruritus, chronic irritation, and tissue fragility, and their increased abundance may result from decreased resilience against pathogens and a pro-inflammatory environment [16]. Overall, alpha species diversity was not altered in LS, but regional differences within the vagina may complicate this finding [9, 10, 16]. Atopobium was dominant in the upper vagina, whereas Bifidobacterium was more prevalent in the lower vagina [18], suggesting that dysbiosis in the setting of LS could be site-specific. Additional studies should be conducted to further understand a potential confounding effect secondary to site sampling. All of these findings suggest subtle shifts in the vaginal microbial population that may contribute to the pro-inflammatory environment present in LS.

Gut microbiome

The gut microbiome of patients with LS demonstrated several alterations. A reduced abundance of Firmicutes was observed in multiple studies and has been linked to a pro-inflammatory environment. Firmicutes are key producers of SCFAs, which play a role in maintaining mucosal integrity and regulating immune responses [11, 15]. Lower levels of Firmicutes may, therefore, lead to a compromised gut barrier and chronic gastrointestinal inflammation. Bacteroides is also a commensal bacterium that produces SCFAs, like butyrate, that stabilize epithelial junctions in the gastrointestinal tract and promote immune homeostasis by modulating T regulatory cell activity [26, 27]. There was a reduction in the abundance of this genus in patients with LS [11, 18]. This reduction may contribute to inflammation and poor immune function, emphasizing the gut microbiome’s potential role in the pathophysiology of LS.

Conversely, Proteobacteria, especially members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, were increased in the gut microbiome of LS patients [11, 15]. These microbes produce lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an endotoxin that activates toll-like receptors, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Elevated levels of LPS due to high Proteobacteria abundance can disturb the intestinal barrier, leading to a leaky gut and exacerbating inflammation [28]. There was also a reported increase in the prevalence of the bacterial family Rikenellaceae, dominant only in LS patients [11, 15], which supports the role of gut dysbiosis as a contributor to immune dysregulation and systemic inflammation in LS. Despite this finding, further studies are certainly warranted to better understand whether these microbial changes precede disease or reflect downstream immune changes secondary to disease progression.

Limitations

The included studies shared several limitations. Most notably, all included studies had small sample sizes and varied designs, which limited their statistical power and generalizability. The majority of these papers utilized 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, which restricts microbe identification to the genus level. Additionally, most studies did not investigate non-bacterial microbes, which may play a role in dysbiosis. Multiple studies also lacked longitudinal data or information on potential confounding factors, including menstrual cycle, hormone levels, sexual activity, and hygiene. These limitations highlight the need for larger longitudinal studies to determine the role of microbial dysbiosis in LS.

| Conclusion | ▴Top |

This systematic review describes the significant alterations in the vulvar, vaginal, and gut microbiomes of patients with LS and suggests that microbial dysbiosis may contribute to the disease’s pathogenesis. Consistent trends included decreases in protective taxa, such as Firmicutes and Lactobacillus, and increases in pro-inflammatory microbes, including Proteobacteria. These observed changes in the microbiome likely contribute to compromised epithelial barriers, disrupt immune regulation, and promote chronic inflammation, leading to tissue fragility and worsening of LS symptoms. There was considerable variability in study design, small sample sizes, and limited assessment of non-bacterial microbes, pointing to the need for more standardized, longitudinal research to clarify the relationships between microbial alterations and disease progression. A better understanding of the microbiome’s role in LS disease progression could potentially influence the development of new diagnostic tools and therapies, while enhancing the quality of life in those who suffer from LS.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Search terms.

Suppl 2. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal checklist for case-control studies.

Suppl 3. Risk of bias assessment using the JBI Critical Appraisal checklist for case-control studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not required as this study did not involve direct human participation or intervention. All data was obtained from previously published studies.

Author Contributions

Sydney Risman: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Una Milovanovic and Derek Weimer: investigation, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Tanya Ramadoss: investigation, formal analysis, and writing – review and editing. Michelle L. Demory: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Data Availability

The data supporting this systematic review are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

ACE: abundance-based coverage estimator; ASV richness: amplicon sequence variant richness; dVIN: differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia; JBI: Joanna Briggs Institute; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; LS: lichen sclerosus; Obs richness: observed richness; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; STIs: sexually transmitted infections; VLS: vulvar lichen sclerosus

| References | ▴Top |

- Kirtschig G. Lichen sclerosus-presentation, diagnosis and management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(19):337-343.

doi pubmed - De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H, Bieber K, Thaci D, Ludwig RJ. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318.

doi pubmed - Perez-Lopez FR, Vieira-Baptista P. Lichen sclerosus in women: a review. Climacteric. 2017;20(4):339-347.

doi pubmed - Gallio N, Preti M, Jones RW, Borella F, Woelber L, Bertero L, Urru S, et al. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia long-term follow up and prognostic factors: An analysis of a large historical cohort. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103(6):1175-1182.

doi pubmed - Singh N, Mishra N, Ghatage P. Treatment Options in Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus: A Scoping Review. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13527.

doi pubmed - Komesu YM, Dinwiddie DL, Richter HE, Lukacz ES, Sung VW, Siddiqui NY, Zyczynski HM, et al. Defining the relationship between vaginal and urinary microbiomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(2):154.e1-e10.

doi pubmed - Chee WJY, Chew SY, Than LTL. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19(1):203.

doi pubmed - Han Y, Liu Z, Chen T. Role of vaginal microbiota dysbiosis in gynecological diseases and the potential interventions. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:643422.

doi pubmed - Pagan L, Huisman BW, van der Wurff M, Naafs RGC, Schuren FHJ, Sanders I, Smits WK, et al. The vulvar microbiome in lichen sclerosus and high-grade intraepithelial lesions. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1264768.

doi pubmed - Liu X, Zhuo Y, Zhou Y, Hu J, Wen H, Xiao C. Analysis of the vulvar skin microbiota in asymptomatic women and patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus based on 16S rRNA sequencing. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:842031.

doi pubmed - Ma X, Wen G, Zhao Z, Lu L, Li T, Gao N, Han G. Alternations in the human skin, gut and vaginal microbiomes in perimenopausal or postmenopausal Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):8429.

doi pubmed - Mousa WK, Chehadeh F, Husband S. Microbial dysbiosis in the gut drives systemic autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:906258.

doi pubmed - Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

doi pubmed - www.rayyan.ai.

- Chattopadhyay S, Arnold JD, Malayil L, Hittle L, Mongodin EF, Marathe KS, Gomez-Lobo V, et al. Potential role of the skin and gut microbiota in premenarchal vulvar lichen sclerosus: A pilot case-control study. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245243.

doi pubmed - Pyle HJ, Evans JC, Artami M, Raj P, Sridharan S, Arana C, Eckert KM, et al. Assessment of the cutaneous hormone landscapes and microbiomes in vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2024;144(8):1808-1816.e1811.

doi pubmed - Brunner A, Medvecz M, Makra N, Sardy M, Komka K, Gugolya M, Szabo D, et al. Human beta defensin levels and vaginal microbiome composition in post-menopausal women diagnosed with lichen sclerosus. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15999.

doi pubmed - Nygaard S, Gerlif K, Bundgaard-Nielsen C, Saleh Media J, Leutscher P, Sorensen S, Brusen Villadsen A, et al. The urinary, vaginal and gut microbiota in women with genital lichen sclerosus - A case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2023;289:1-8.

doi pubmed - Tsai YC, Tai WC, Liang CM, Wu CK, Tsai MC, Hu WH, Huang PY, et al. Alternations of the gut microbiota and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio after biologic treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2025;58(1):62-69.

doi pubmed - Samaddar A, van Nispen J, Armstrong A, Song E, Voigt M, Murali V, Krebs J, et al. Lower systemic inflammation is associated with gut firmicutes dominance and reduced liver injury in a novel ambulatory model of parenteral nutrition. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1701-1713.

doi pubmed - Lithgow KV, Buchholz VCH, Ku E, Konschuh S, D'Aubeterre A, Sycuro LK. Protease activities of vaginal Porphyromonas species disrupt coagulation and extracellular matrix in the cervicovaginal niche. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2022;8(1):8.

doi pubmed - Petrova MI, Reid G, Vaneechoutte M, Lebeer S. Lactobacillus iners: Friend or Foe? Trends Microbiol. 2017;25(3):182-191.

doi pubmed - Zheng N, Guo R, Wang J, Zhou W, Ling Z. Contribution of lactobacillus iners to vaginal health and diseases: a systematic review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:792787.

doi pubmed - Tett A, Pasolli E, Masetti G, Ercolini D, Segata N. Prevotella diversity, niches and interactions with the human host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(9):585-599.

doi pubmed - Alauzet C, Marchandin H, Lozniewski A. New insights into Prevotella diversity and medical microbiology. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(11):1695-1718.

doi pubmed - Kim CH. Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20(4):341-350.

doi pubmed - Zhang D, Jian YP, Zhang YN, Li Y, Gu LT, Sun HH, Liu MD, et al. Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):212.

doi pubmed - Rizzatti G, Lopetuso LR, Gibiino G, Binda C, Gasbarrini A. Proteobacteria: a common factor in human diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:9351507.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.