| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 4, December 2025, pages 189-194

Spontaneous Adrenal Hemorrhage in Pregnancy

Marvi Memona, c, Donald Wilsona, Isioma Okoloa, Amy Wangb

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Forth Valley Royal Hospital, Labret FK5 4WR, Scotland, UK

bDepartment of Radiology, Forth Valley Royal Hospital, Larbert FK5 4WR, Scotland, UK

cCorresponding Author: Marvi Memon, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Forth Valley Royal Hospital, Larbert FK5 4WR, Scotland, UK

Manuscript submitted August 28, 2025, accepted November 28, 2025, published online December 11, 2025

Short title: Spontaneous Adrenal Hemorrhage in Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1538

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage (SAH) is a rare condition that may lead to life-threatening adrenal insufficiency or adrenal crisis if not addressed appropriately. Abdominal pain during pregnancy has a broad differential diagnosis, which includes SAH. There are very few studies on the precipitating factors, management, and optimal mode of delivery. We present a 32-year-old multiparous woman who presented at 33 weeks of gestation with right-sided flank pain. The initial ultrasound of the abdomen was unremarkable. The diagnosis of SAH was made by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen, and the patient management included analgesia, serial hemoglobin assessments, and clinical examination which resulted in uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She was followed up with endocrinology at 3 months with plan for repeat MRI of the abdomen. SAH, although rare, is an important consideration when evaluating abdominal and flank pain during pregnancy. It is a challenging diagnostic and therapeutic condition. The management options vary from conservative management to surgical intervention depending on the stability of the patient. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach is a very crucial aspect of diagnosis and management of this rare condition.

Keywords: Adrenal hemorrhage; Adrenal crisis; Life-threatening; Diagnosis; Challenging

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage (SAH) is defined as acute hemorrhage of the adrenal gland, without any prior trauma or history of anticoagulation and occurring without any predispositions [1]. Abdominal pain is a common complaint during pregnancy and encompasses a wide differential diagnosis, including the rare but potentially life-threatening condition of SAH. The incidence of adrenal hemorrhage in pregnancy is currently not known; however, an association with pregnancy has been reported [1, 2]. Many autopsy studies have stated that the incidence of adrenal hemorrhage ranges from 0.03% to 1.8%, with a higher incidence of up to 25% following trauma [2]. Diagnosis can be challenging, as SAH often presents with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal or flank pain and fever [1, 2]. In rare instances, patients may develop massive retroperitoneal bleeding, leading to hemodynamic instability [2, 3]. When hemorrhage is bilateral, it can precipitate adrenal crisis and shock, sometimes necessitating emergency laparotomy and adrenalectomy [2, 3]. The overall mortality rate for adrenal hemorrhage has been reported as 15% but this may vary depending on the delay in diagnosis, prompt treatment, and individual underlying illnesses [3]. We present a case of symptomatic SAH that occurred in the third trimester of pregnancy and was managed conservatively.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 32-year-old multiparous woman presented at 33 + 4 weeks of gestation with less than 24 h of acute severe right subcostal pain radiating to her right flank. The pain was dull in nature. She denied any urinary or gastrointestinal symptoms. She had two previous uneventful pregnancies, both ending in term vaginal births. She had a body mass index (BMI) of 44, which was consistent with a venous thromboembolism score of 2 [4]. Past medical and surgical history did not reveal any significant findings.

Her initial examination revealed a blood pressure (BP) of 102/69, a heart rate of 94 beats/min, a temperature of 36.6 °C, and 98% oxygen saturations in room air. Abdominal examination revealed a soft, palpable, gravid uterus with no signs of peritonism but tender on palpation in the right flank region. There were no signs of preterm labor, and fetal status was reassuring, with normal cardiotocographic traces. Antenatal ultrasound scans were normal, with a live fetus and no gross malformations.

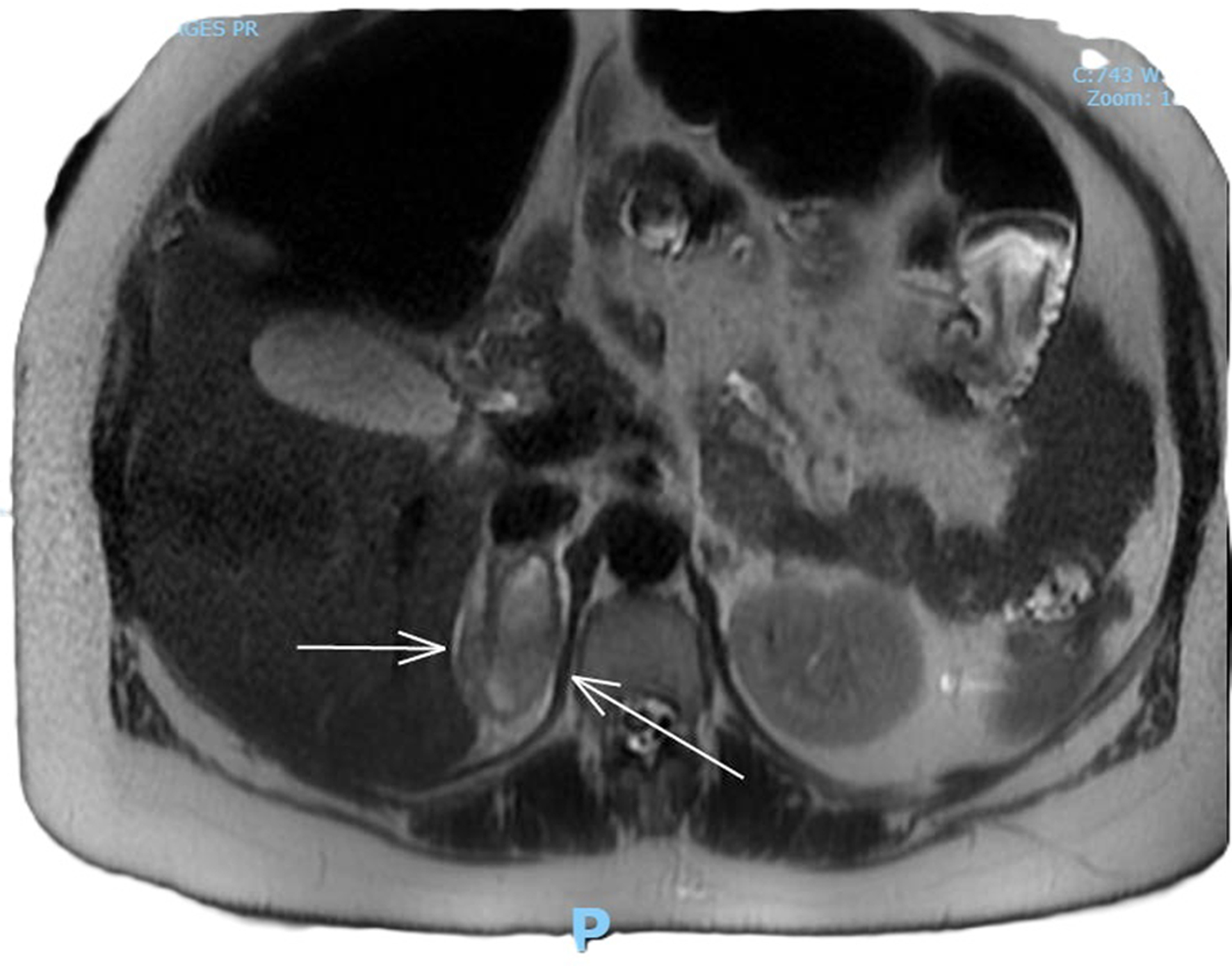

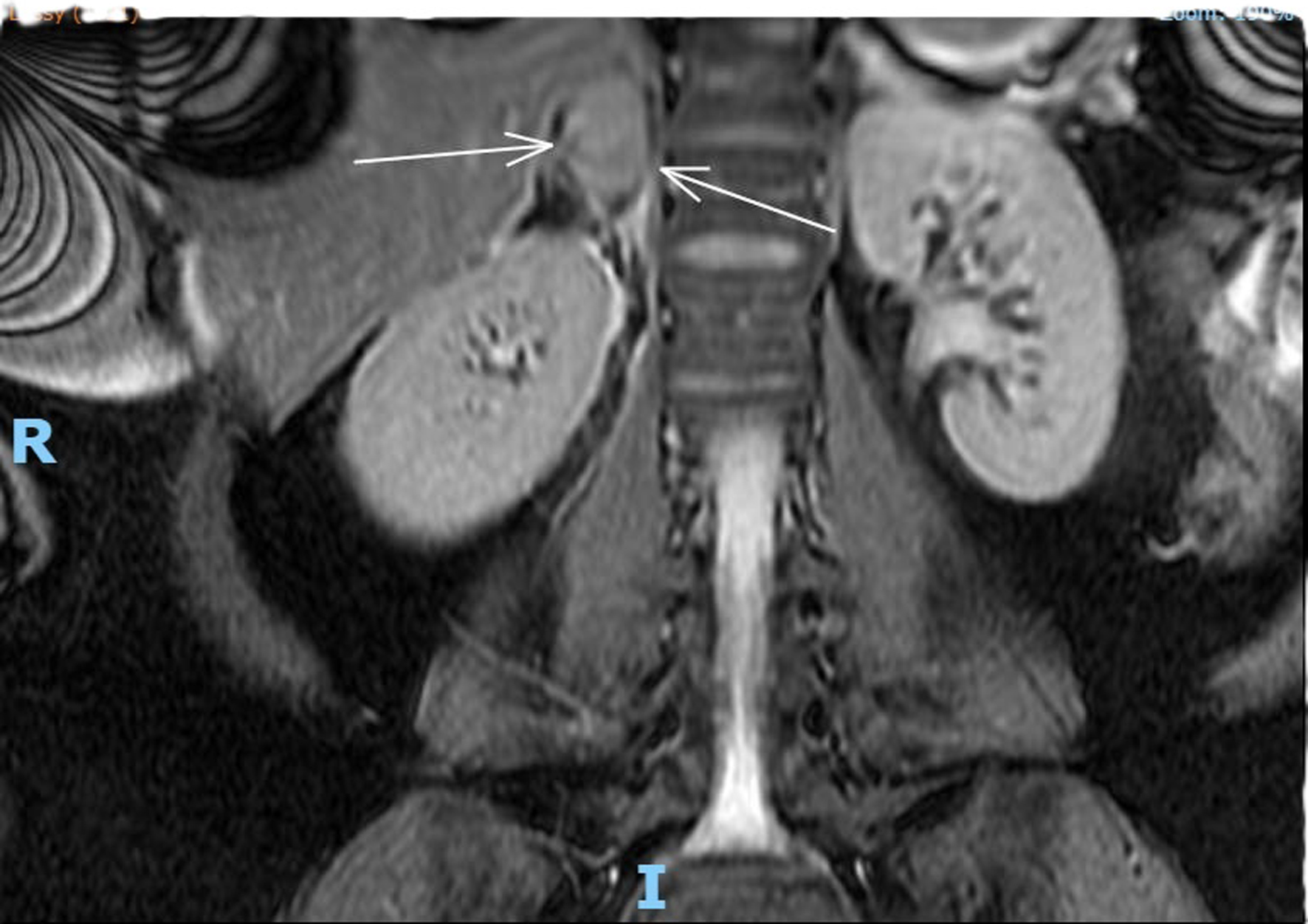

Complete full blood count, coagulation profile, liver function test, renal function test, and amylase were all within normal limits, with a total hemoglobin concentration of 122 g/dL, total leucocyte count of 9,600 mL, normal platelet count, C-reactive protein concentration of 6 mg/L, bile acid concentration of 1.8 µmol/L, creatinine concentration of 46 µmol/L, urea concentration of 1.9 mmol/L, and potassium level indeterminate because of hemolyzed specimen. Urine analysis was negative. Renal ultrasound revealed no evidence of hydronephrosis, mass, or calculi. An obstetric ultrasound performed 1 week prior revealed a live fetus with a normal anterior placenta and appropriate fetal growth with a normal liquor volume and umbilical artery Doppler. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal appearance of the gallbladder, no evidence of gallstones, a normal caliber of the common bile duct, and no focal abnormality or ascitic fluid identified with an obscured appendix. The patient was admitted and continued to experience persistent right flank pain with three episodes of vomiting and nausea. She experienced generalized fatigue and malaise 3 days post admission. Intravenous fluids and oral opioids were used to control pain. General surgery colleagues were consulted to rule out surgical causes of acute abdomen and concerns for possible related complications. On review of her investigations, there was a significant decrease in the hemoglobin level to 88 g/dL, a new increase in potassium to 9.6 mmol/L, chloride 117 mmol/L, and a significant steep increase in C-reactive protein levels of 101 and 233 mg/L. An MRI scan of the abdomen (Fig. 1) revealed coronal plane, T2-weighted sequence demonstrating an area of heterogeneous high T2 signal density. An arrow points to enlarged adrenal gland consistent with adrenal hemorrhage. MRI transverse plan (Fig. 2) revealed T2-weighted sequence demonstrating a 44 × 54 × 25 mm lesion centered in right adrenal gland with heterogeneous T2 signal compatible with spontaneous/acute adrenal hemorrhage. A trace amount of fluid surrounding the adrenal gland and right kidney is consistent with SAH. Transverse plane (Fig. 3) high T2 density signals showed enlarged adrenal gland.

Click for large image | Figure 1. MRI coronal plane, T2-weighted sequence demonstrating an area of heterogeneous high T2 signal density. An arrow points to enlarged adrenal gland consistent with adrenal hemorrhage. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. MRI transverse plan, T2-weighted sequence demonstrating a 44 × 54 × 25 mm lesion centered in right adrenal gland with heterogeneous T2 signal compatible with spontaneous/acute adrenal hemorrhage. A trace amount of fluid surrounding the adrenal gland and right kidney is consistent with SAH. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Transverse plane, high T2 density signals showing enlarged adrenal gland. |

Differential diagnosis

Over the course of presentation, our differential diagnosis included appendicitis with atypical presentation due to a gravid uterus, pyelonephritis, renal stones, renal hydronephrosis, pulmonary embolism, musculoskeletal pain, and pre-eclampsia.

Pulmonary embolism was unlikely as there were normal blood gases and saturations on air. Musculoskeletal pain was also unlikely considering that there was no associated history. Renal ultrasound did not reveal any hydronephrosis or signs of pyelonephritis or stones. BP was normal with no proteinuria. Considering pancreatitis, it was ruled out by normal amylase levels with normal abdominal ultrasound. After MRI, diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage was made.

Treatment

The patient was managed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), including anesthesia, general surgical, and endocrinology teams. Her laboratory evaluation revealed a morning cortisol level of 550 nmol/L which was performed on the day 4 of her acute presentation and she planned to start hydrocortisone only if her BP decreased or if the patient became hemodynamically unstable. She was started on intravenous cefuroxime 1.5 g every 8 h for infection prophylaxis. Analgesia included percutaneous morphine (PCM) and codeine. She was monitored with serial hemoglobin assessments, frequent BP measurements, and clinical examinations. The patient remained clinically and hemodynamically stable and did not require hydrocortisone. After 1 week, the patient’s laboratory examination revealed hemoglobin of 121 g/L, normal total leukocyte count and platelet count, and potassium level of 4.3 mmol/L. The C-reactive protein concentration was 47 mg/L. She was successfully weaned from PCM and transitioned to oral pain medications, namely, dihydrocodeine and completed oral cefuroxime course of 7 days. The fetal heart rate tracing (FHRT) remained reassuring with normal baseline, good variability presence of acceleration, with no decelerations. She was discharged home with follow-up at the combined obstetrics, antenatal, and endocrinology outpatient clinic.

Follow-up and outcomes

She was reviewed at a combination of obstetrics and endocrinology clinics. She has remained clinically well, with normal BP readings every week since her discharge from the hospital. The MDT approach, involving obstetrics, anesthesia, midwifery, and endocrinology opinions was sought to determine the optimal mode of delivery. Our main concern was the risk of recurrent spontaneous hemorrhage because of an increase in abdominal pressure during normal vaginal birth, although there is no evidence in the literature regarding this risk.

The patient subsequently returned at 38 + 4 weeks of gestation for induction of labor due to a large for gestation baby as per local protocol. She delivered vaginally with no complications or emergency interventions. Postpartum she remained well and was discharged home on the second day of vaginal birth. The patient was further advised to follow up with the endocrinology outpatient clinic at 3 months with repeat MRI of the abdomen to confirm complete resolution of the adrenal hemorrhage.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

SAH is a condition that is difficult to recognize clinically. First, owing to its low incidence, SAH is often missed when a list of differential diagnoses is developed [5]. If unrecognized, adrenal hemorrhage can lead to adrenal crisis, shock, and theoretically death for both mother and fetus and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain during pregnancy [5].

To be classified as spontaneous or idiopathic, there can be no history of trauma, anticoagulation, tumor, or sepsis [5, 6]. The common presentations include non-specific pain located in the epigastrium, flank, upper or lower back, and pelvis in 65-85% of cases [5, 6]. Symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, such as fatigue, weakness, dizziness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, and diarrhea, are present in appropriately 50% of extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage cases [5, 6].

It is imperative to consider the potential for bilateral SAH in patients who have experienced unilateral SAH [6]. The data were gathered from eight publicly accessible studies, which collectively described nine patients with an incidence of SAH during pregnancy. Anemia was reported in four cases, with one instance being severe. Four cases reported hormonal deviations, with one instance of adrenal insufficiency. Four patients underwent caesarean-section delivery, while three underwent spontaneous labor. Two patients experienced premature birth. In two cases, the surgical procedure of adrenalectomy was performed [6].

The pathophysiology of adrenal hemorrhage in nontraumatic cases is unclear. The usual hypothesis is that in pregnancy, there is associated adrenal cortical hyperplasia, which in turn may predispose individuals to venous congestion and subsequently to hemorrhage [7, 8]. During periods of hemodynamic stress, an increase in adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) promotes blood flow to the adrenal glands, while simultaneously, a catecholamine surge constricts venous circulation, increasing pressure, promoting platelet aggregation, and eventually leading to rupture of thin-wall edging vessels, resulting in hemorrhage and infarction [7, 8].

Common causes of adrenal hemorrhage include trauma, stress, surgery, sepsis, burns, pregnancy anticoagulation or coagulopathy. Adrenal tumors like adenoma and pheochromocytoma also predisposed to adrenal hemorrhage [8]. One of the most common causes of adrenal hemorrhage is trauma. However, in the context of SAH, certain predispositions have been studied, most notably stress, antiphospholipid syndrome, and the use of anticoagulants [8, 9].

Laboratory findings may vary from normal values to acute adrenal insufficiency, accompanied by hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, profound hypoglycemia, leucocytosis, and falling hematocrit level [8, 9]. In the recent literature, there appears to be no general consensus on whether computed tomography (CT) or MRI is the most accurate in confirming the diagnosis of an adrenal hemorrhage. Despite this, both appear to be invaluable, and each has characteristic findings on their images [8, 9]. An ultrasound is the primary imaging modality of choice during pregnancy; however, MRI has high sensitivity and specificity for hemorrhage and ruling out underlying causes such as adrenal tumors as well as ruling out other differential diagnoses [9, 10].

In hemodynamically stable patients, conservative management should focus on steroid therapy, fluid resuscitation, pain management, maintaining hemodynamic stability, and correction of underlying coagulopathies or comorbidities that may exaggerate symptoms [11]. In hemodynamically unstable patients, surgery may be indicated to maintain adrenal sufficiency and prevent circulatory collapse. Adrenalectomy can be safely performed in pregnancy [11, 12]. In the context of an adrenal tumor in pregnancy, adrenalectomy is preferably performed in the second trimester or deferred until after delivery if it is diagnosed in late third trimester [11, 12].

There is a paucity of studies in the literature on the optimal mode of delivery in patients with SAH [12, 13]. Preterm delivery may be needed if the SAH is progressive or associated with severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia or other obstetric indications, and, therefore, timely antenatal corticosteroids or magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) may be required for fetal optimization [12, 13]. Having mortality risk of 15% in the general population, it is potentially life-threatening to both mother and the fetus if not identified early [13]. Furthermore, it is recommended that adrenal function be assessed postpartum, as stress associated with labor has the potential to precipitate a relapse [14]. It is imperative to evaluate adrenal function, as fatal adrenal insufficiency secondary to SAH has been documented in postpartum patients [14]. A follow-up MRI or CT scan is recommended to confirm whether the hemorrhage has stabilized or resolved [14].

Learning points

Although SAH is rare, it is a vital consideration when evaluating abdominal and flank pain during pregnancy. Abdominal ultrasound is a primary modality of investigation, but MRI of the abdomen in pregnancy has high sensitivity and specificity for making a diagnosis. MDT collaboration is a vital part of management. Patients with unilateral adrenal hemorrhage are managed conservatively because there is no associated decrease in BP due to the contralateral functioning adrenal gland. Steroid therapy is an important part of management in patients with adrenal crisis. There is no recommended mode of delivery, but a normal vaginal delivery is considered the optimal mode of delivery for uncomplicatedly resolving unilateral adrenal hemorrhage. Preterm delivery should be considered if associated with severe pre-eclampsia, coagulopathies or other obstetric disorders.

Patient’s perspective

The experience I went through was terrible and the intensity of pain was unbearable. When I was told that this condition is rare and requires multiple specialist care that actually reassured me and I was cared with meticulous broad team approach and recovered from this condition. But I realized there is no enough evidence available for optimal management of this condition therefore I agreed and gave consent for sharing my case for future generations and also asked for participating in any help if needed.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the medical staff, midwives, and whole team of Forth Valley Royal Hospital involved in care of this patient.

Financial Disclosure

The authors or the institution responsible for this case report did not at any time receive payment or services from a third party (government, commercial, private foundation, etc.) for any aspect of the submitted work.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Informed Consent

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient to use her anonymized clinical information for the purpose of this reporting. Informed consent was taken from all other medical staff involved in care of this patient.

Author Contributions

All authors offered intellectual insight, aided in the drafting, editing, and critical review of this work, and gave final approval for submission after proper analysis of data, facts, and figures. Marvi Memon (corresponding and first author) was involved in direct patient care, data collection, consent taking, literature search, and writing manuscript. Isioma Okolo (consultant) was involved in patient care, consent taking, and data collection. Donald Wilson helped in writing manuscript, analysis of data, proofreading of manuscript, editing, and formatting. Amy Wang helped in selecting MRI images, highlighting diseased real in images and reporting images.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Further data will be available from corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

ACTH: adrenocorticotrophic hormone; SAH: spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography; BP: blood pressure; BMI: body mass index; FHRT: fetal heart rate tracing; PCM: percutaneous morphine; MDT: multidisciplinary team; MgSO4: magnesium sulphate

| References | ▴Top |

- Gavrilova-Jordan L, Edmister WB, Farrell MA, Watson WJ. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage during pregnancy: a review of the literature and a case report of successful conservative management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60(3):191-195.

doi pubmed - Gupta A, Minhas R, Quant HS. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage in pregnancy: a case series. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;2017:3167273.

doi pubmed - Wani MS, Naikoo ZA, Malik MA, Bhat AH, Wani MA, Qadri SA. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage during pregnancy: review of literature and case report of successful conservative management. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2011;12(4):263-265.

doi pubmed - Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium green-top Guideline No. 37a. 2015.

- Desai P, Pandey B, Nava H, Kc A, Trester R. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage in pregnancy. J. Clin. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024;13:18-22.

doi - Skolozdrzy T, Wojciechowski J, Halczak M, Ciecwiez SM, Zietek M, Romanowski M. Successful conservative treatment of maternal spontaneous unilateral adrenal hemorrhage causing severe anemia in the third trimester of pregnancy-a case report. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(9):1448.

doi pubmed - Mehmood KT, Sharman T. Adrenal hemorrhage. StatPearls-NCBI Bookshelf. (Accessed on July 13, 2024) Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555911/.

- Di Serafino M, Severino R, Coppola V, Gioioso M, Rocca R, Lisanti F, Scarano E. Nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage: the adrenal stress. Radiol Case Rep. 2017;12(3):483-487.

doi pubmed - Patel E, Zill EHR, Demertzidou E. Spontaneous adrenal haemorrhage in pregnancy and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(5):e246240.

doi pubmed - Shantha N, Granger K. Spontaneous adrenal haemorrhage in early pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(4):449-451.

doi pubmed - Bockorny B, Posteraro A, Bilgrami S. Bilateral spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(2 Pt 1):377-381.

doi pubmed - Singh M, Sinha A, Singh T. Idiopathic unilateral adrenal hemorrhage in a term pregnant primigravida female. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15(9):1541-1544.

doi pubmed - Cheng MW, Khan K. A case report of spontaneous unilateral adrenal hemorrhage in the third trimester of pregnancy. Cureus. 2025;17(9):e93217.

doi pubmed - Badawy M, Gaballah AH, Ganeshan D, Abdelalziz A, Remer EM, Alsabbagh M, Westphalen A, et al. Adrenal hemorrhage and hemorrhagic masses; diagnostic workup and imaging findings. Br J Radiol. 2021;94(1127):20210753.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.