| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

A Challenging Case of Malignant Struma Ovarii With Concurrent Papillary Thyroid Cancer

Angelica Stephanie K. Munoza, b, c, Jeffrey Jen Hui Lowa

aDivision of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National University Hospital Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

bDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Medical Center, Pampanga, Philippines

cCorresponding Author: Angelica Stephanie K. Munoz, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Medical Center, Pampanga, Philippines

Manuscript submitted May 27, 2025, accepted July 23, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: MSO With Concurrent Papillary Thyroid Cancer

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1522

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Struma ovarii is a rare type of ovarian tumor that is predominantly composed of thyroid tissue. The majority of these are benign, with malignant struma ovarii (MSO) comprising only 5-10% of all cases. A 41-year-old female with a history of ovarian cystectomy for bilateral dermoid cysts presented with gallstone pancreatitis. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed adnexal masses, peritoneal nodules, and a thyroid nodule. Surgery, including total hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy, showed MSO and differentiated follicular carcinoma. Subsequent thyroidectomy revealed multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. Postoperative radioactive iodine therapy was given, and the patient has recovered fully. MSO may present as an ovarian mass, and the mainstay treatment is surgical resection. The rarity of this condition requires a multidisciplinary approach for optimal management. MSO should be considered in the differential diagnosis of ovarian masses. Early and accurate diagnosis, followed by appropriate surgical and adjuvant therapies, can lead to favorable outcomes.

Keywords: Malignant struma ovarii; Ovarian tumor; Thyroid tissue; Total thyroidectomy; Radioiodine therapy; Multidisciplinary management

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Struma ovarii is a highly specialized monodermal teratoma wherein the thyroid tissue comprises at least 50% of the tumor mass [1, 2]. It accounts for approximately 5% of all ovarian teratomas [2]. Symptoms are nonspecific, and women are mostly asymptomatic or may present with abdominal pain and/or a pelvic mass, and less frequently with ascites [3]. Even though these tumors contain a significant amount of thyroid tissue, only 5-8% of patients present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism [4].

Histologically, the majority of struma ovarii are benign. Malignant struma ovarii (MSO) is very rare and comprises 5-10% of all struma ovarii [5, 6]. Here, we present a case of a patient diagnosed with MSO with concurrent papillary thyroid carcinoma.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 41-year-old woman, G1P1(1001), with a known history of hypertension underwent laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy in 2011 for bilateral dermoid cysts. In 2017, routine ultrasound revealed a left ovarian cyst, 4.2 × 3.0 × 3.0 cm, heterogeneous with an echogenic avascular component, and right ovarian likely hemorrhagic cysts measuring 1.8 × 1.5 × 1.8 cm and 2.1 × 1.5 × 1.5 cm. At this time, she was asymptomatic and opted serial ultrasound monitoring. The ovarian cysts remained relatively stable until 2021, when an ultrasound showed a multiloculated (> 10 locules), heterogeneous and irregular left adnexal mass measuring 9.2 × 5.5 × 5.2 cm, containing a vascular 2.8 × 2.2 × 1.9 cm echogenic solid component. In the right adnexa, there were two cysts noted: first, between the right ovary and uterus, a heterogeneous predominantly solid mass of 2.1 × 1.1 × 1.6 cm, with peripheral vascularity, and with a few cystic locules within; and second, in the lateral aspect of the right adnexa, a heterogeneous predominantly solid mass of 3.2 × 3.2 × 1.8 cm with internal vascularity. Due to the increase in size and suspicious nature of the adnexal masses, the patient was advised to undergo further evaluation but defaulted.

Five months later, she presented with severe epigastric pain and vomiting and was diagnosed to have gallstone pancreatitis with choledocholithiasis. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis done at this time also showed heterogeneous masses in both adnexa (left 8.0 × 4.8 cm, right 4.8 cm), multiple enhancing peritoneal nodules with small volume ascites and a right thyroid nodule. She eventually underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and intraoperatively, the surgeon noted multiple small cystic lesions on the ovarian and uterine surfaces, and small omental nodules. Biopsies of the ovarian and peritoneal nodules were reported to have thyroid tissue present, which could represent portions of struma ovarii or struma peritonei or a thyroid component of a teratoma, and despite the benign histological appearance, malignancy of the thyroid tissue component could not be ruled out due to peritoneal involvement. Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) was slightly elevated at 45 U/mL.

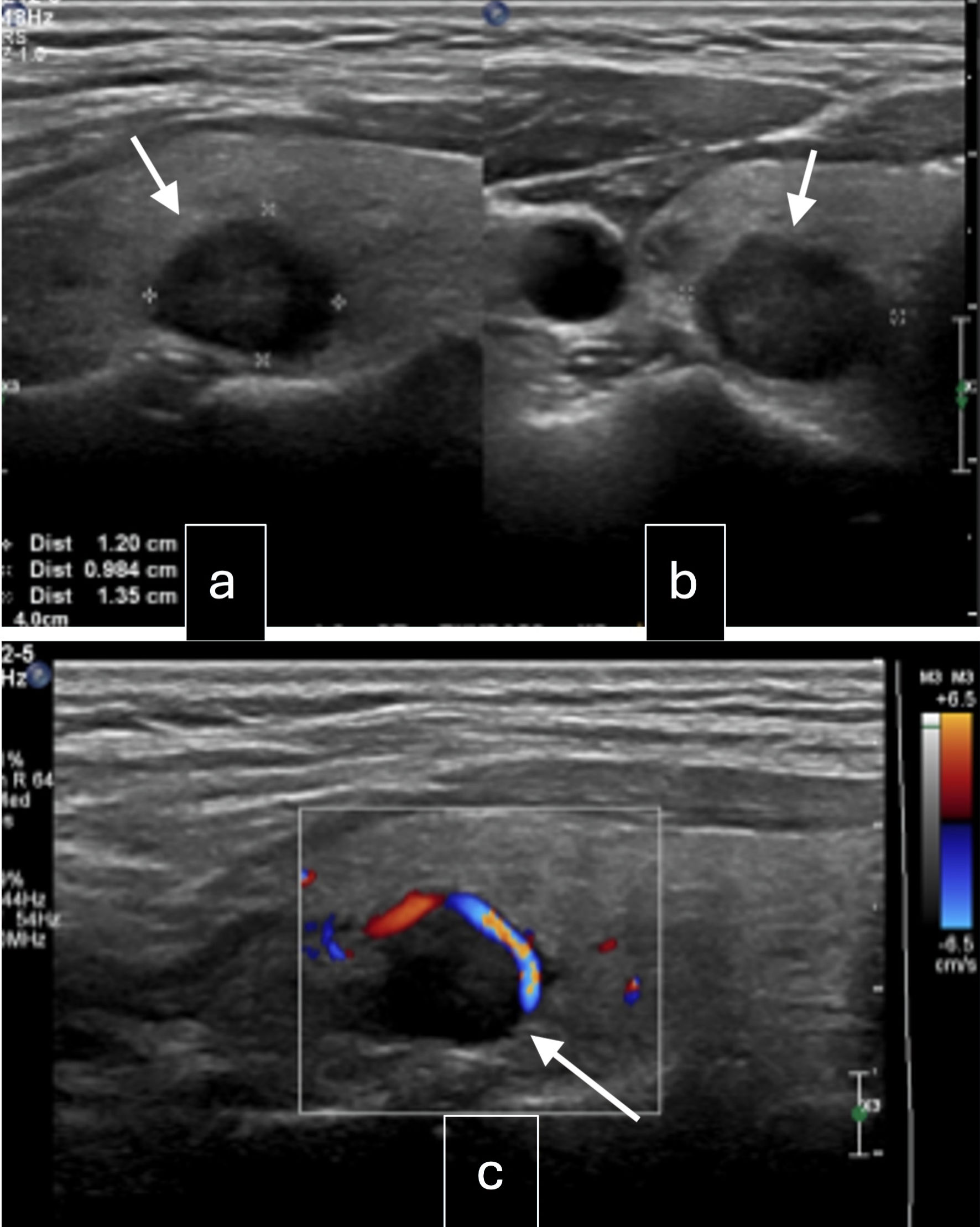

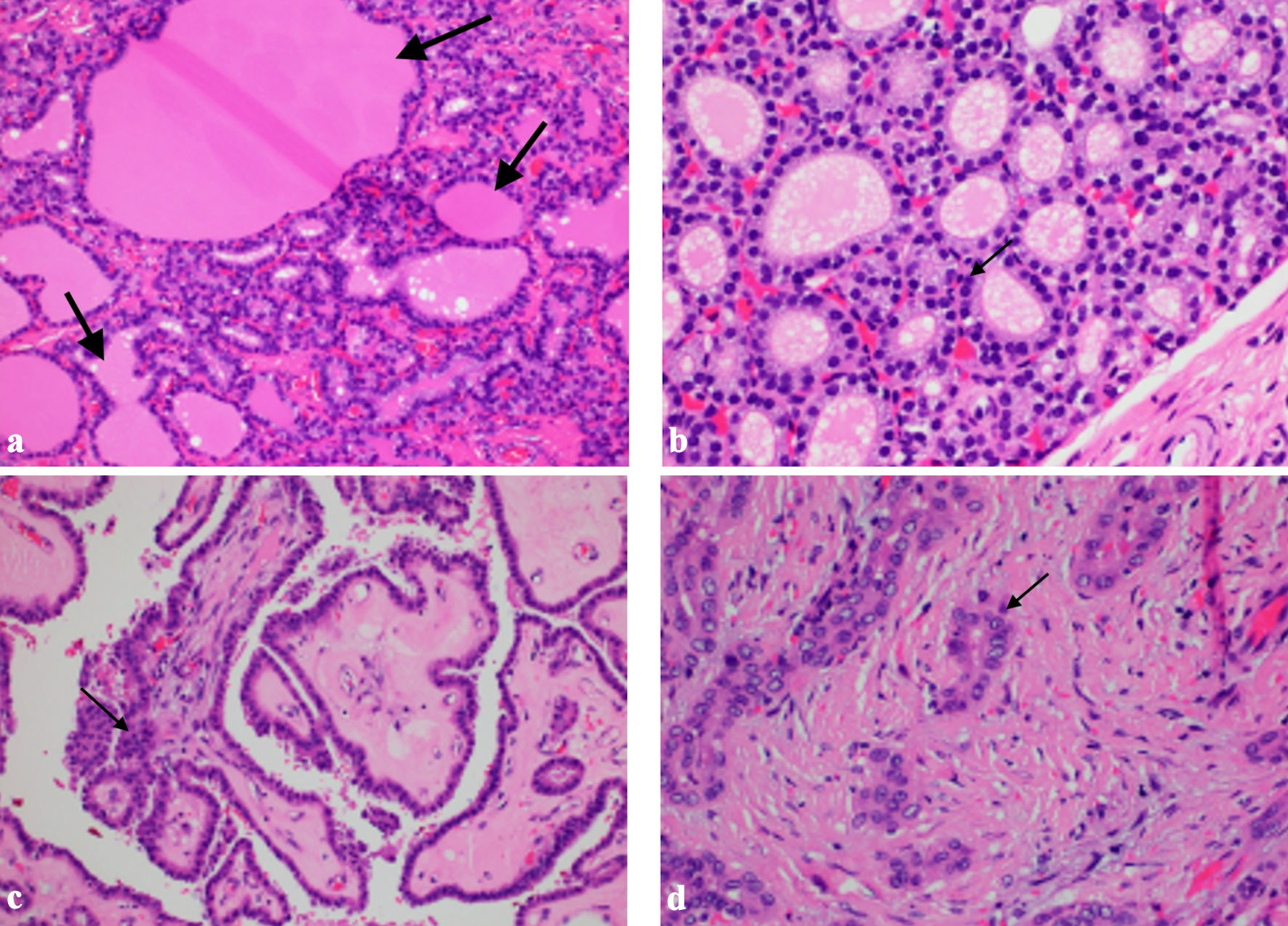

The patient was then referred to our institution for further management. Her case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting. Thyroid function tests were normal, while thyroglobulin (TG) was elevated at 1,066 µg/L. She was referred to ear, nose and throat (ENT) and endocrinology for further assessment of the thyroid nodule. Ultrasound of the thyroid gland (Fig. 1) showed multiple solid thyroid nodules in both lobes, with the dominant nodule in the right middle pole at 1.2 × 1.4 × 1 cm, and a left cervical lymph node of 1.4 × 1.0 × 0.6 cm heterogeneous, with no fatty hilum and no hilar vascularity. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the right thyroid nodule showed a follicular neoplasm with nuclear atypia, with a 25-40% risk of malignancy. The patient was advised to have staged surgeries. Laparotomy, total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), omentectomy, resection of peritoneal and sigmoid tumor nodules, and nodal debulking were performed. Intraoperatively, the left ovary was enlarged to 10 × 8 cm, while the right ovary was enlarged to 5 × 5 cm. There were multiple tumor nodules on the omentum, serosal surfaces of the rectosigmoid colon, pelvic peritoneum, rectal epiploicae, and anterior peritoneum. Bulky right obturator and right precaval lymph nodes were removed. The liver, small bowel, and appendix appeared normal. There was no residual disease at the end of the surgery. Final histology showed bilateral ovarian struma ovarii (Fig. 2a, b) with tumor deposits on the surface of both ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterine serosa and multiple nodular tumor deposits of thyroid tissue in the omentum, sigmoid nodule, and pelvic peritoneal nodules. Lymph nodes taken were negative. Given the size of the primary tumors and the presence of tumor deposits in multiple extra-ovarian sites, malignant transformation in struma ovarii with a highly differentiated follicular carcinoma was considered.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Ultrasound of the neck. (a) Right lobe mid pole nodule: well-circumscribed, solid, iso-hypoechoic, wider than tall with peripheral vascularity, 14 × 12 × 10 mm (arrow, intermediate suspicion). (b) Right lobe upper pole nodule: spongiform lesion, 6 × 4 × 3 mm (arrow, low suspicion). (c) Left lobe mid pole nodule: well-defined, solid, hypoechoic lesion with coarse internal calcifications, 7 × 7 × 5 mm (arrow, intermediate suspicion). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Histology images. (a) Struma ovarii tissue with evidence of thyroid follicular tissue with colloid seen within the follicles (arrows, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) × 20). (b) Struma ovarii tissue showing dense nuclei with no nuclear atypia (arrow, HE × 40). (c) Papillary thyroid carcinoma showing classical papillary formations, crowded overlapping nuclei (arrow, HE × 20). (d) Papillary thyroid carcinoma showing nuclear grooves, pseudoinclusions and central clearing (arrow) |

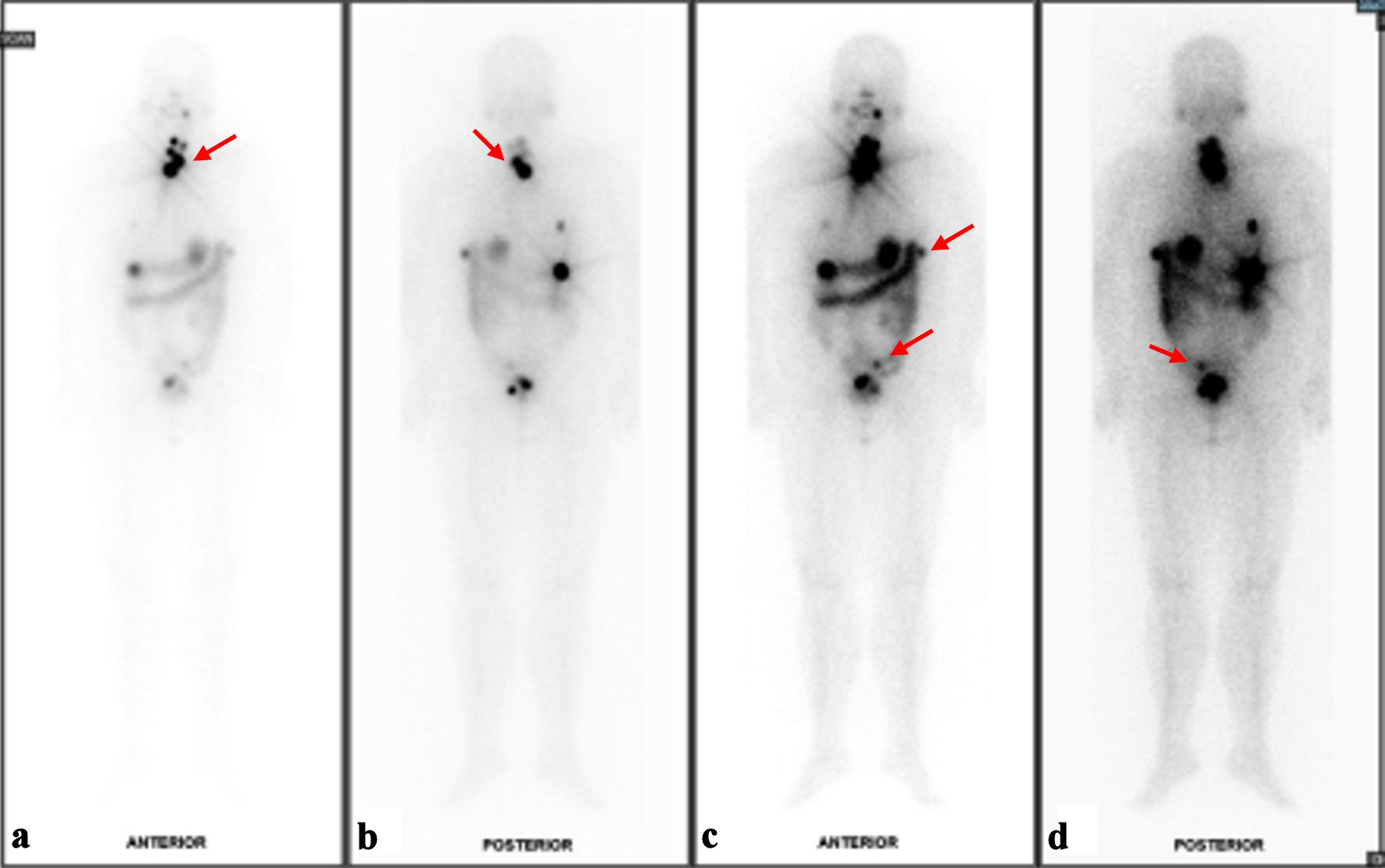

The next part of management was a total thyroidectomy and adjuvant radioiodine therapy. Furthermore, a second pathology was considered for the thyroid gland as an independent thyroid follicular neoplasm due to the difference in nuclear appearance on FNA. Repeat TG level 2 weeks postoperatively was already significantly lower at 117.1 µg/L. The patient underwent total thyroidectomy 2 months later. Histology of the thyroid gland showed classic-type multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma (Fig. 2c, d), stage II T2N0M1, with no extension to skeletal muscle or adjacent structures and no lymphovascular invasion. She then underwent radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy with a dose of 150 mCi, and I131 whole body scan was performed 72 h post RAI (Fig. 3a-d). Prior to RAI, the TG level was 112 µg/L, anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) was < 3.0 IU/mL, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was 60.86 pmol/L, and free thyroxine (FT4) was 5.6 pmol/L. The patient was doing well and had fully recovered from both surgeries. As discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting, the patient was scheduled to undergo imaging and laboratory tests every 6 months as surveillance. The patient has undergone CT of the abdomen and pelvis, as well as thyroid ultrasound, which have all been clear of disease, showing no residual nodules. Biochemical response has been monitored with TG, thyroid function tests and CA125, which have remained within normal since completion of treatment. She will continue long-term follow-up as there are reports of recurrence even 20 years after initial treatment [7].

Click for large image | Figure 3. Results of I131 whole body scan (WBS). (a) Foci of I131 uptake at the anterior neck likely represent remnant thyroid tissues although small volume disease cannot be ruled out on current baseline study (red arrow). (b) Posterior view of likely remnant thyroid tissues versus small volume disease (red arrow). (c) Several I131-avid foci in the upper abdomen and pelvic cavity with corresponding peritoneal nodules/nodularities are suspicious for residual disease (red arrows). (d) Indeterminate I131-avid focus at the sigmoid colon region (red arrow). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Struma ovarii is seen more commonly between the ages of 40 - 60 years. MSO has been reported to occur more in women in their 30s to 40s [7, 8]. Clinical guidelines on the diagnosis and management of MSO are lacking due to the rarity of this disease entity. Preoperative clinical and radiological diagnosis of MSO is difficult since there are no distinguishing clinical and radiological features [3, 4]. Like most ovarian masses, it may present with abdominal pain and a pelvic mass. In a study done by Ayhan et al, which reviewed 178 cases of MSO, 64% of patients presented with abdominal symptoms, while 18.5% were asymptomatic [4]. The majority of patients (90.4%) presented with a unilateral ovarian mass, while bilaterality was seen in 7.9% [6]. In a study done by Yoo et al, around 41.2% of cases were found incidentally during routine sonograms [3].

Ovarian tumor markers such as CA-125 may be elevated, but provide little value in diagnosis [3, 9]. Imaging modalities such as ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly used; however, findings are nonspecific, and many cases are thought to be ovarian malignancy. Struma ovarii generally contain solid components or thickened septa in the cystic component. Sonography may show a heterogeneous, predominantly solid mass, but there are no distinguishing features that support the diagnosis, although some have reported findings of a struma pearl, which appears as a smooth, roundish solid area [8, 10]. CT may show a complex cystic-solid mass, with intracystic high attenuation lesions, which are thought to correspond to viscid gelatinous colloid material [10]. Since conventional imaging modalities have limitations in the diagnosis of struma ovarii, Fujiwara et al have proposed the use of 131I scintigraphy in combination with an fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) scan in cases where there is a high index of suspicion. Further studies are needed to establish their utility [10].

The definitive diagnosis of MSO is often made postoperatively on histological analysis. Uniformly accepted criteria for diagnosis of MSO have not yet been established. Currently, the diagnostic criteria for MSO are similar to those for thyroid cancer. Different types of thyroid carcinoma arising in struma ovarii include papillary carcinoma (including the follicular variant), follicular carcinoma (including the oncocytic variant), and insular carcinoma [9]. In the study done by Cui et al which reviewed 144 cases, there were six types of MSO seen: papillary thyroid carcinoma accounted for 50% of cases, follicular carcinoma accounted for 26.47%, follicular variant of papillary carcinoma accounted for 18.63%, anaplastic carcinoma accounted for 0.98% and medullary carcinoma accounted for 0.98% [9].

The most common thyroid-type carcinoma arising in struma ovarii is papillary carcinoma [9]. Histologically, overlapping, ground-glass, irregularly contoured nuclei lining papillary formations with fibrovascular cores or vascular invasion can be seen. Psammoma bodies are also highly supportive of a diagnosis of malignancy. The second most common type of carcinoma arising from struma ovarii is follicular carcinoma [9]. The majority of patients diagnosed with MSO are confined to the ovary, with the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I in 76.9%, stage II in 1.1%, stage III in 6.8%, and stage IV in 5.7% [4]. In the case presented, MSO tumor deposits were seen in the peritoneum, omentum, serosa of the sigmoid, fallopian tubes, and uterine serosa, classifying her as a FIGO stage 3 case.

Synchronous primary thyroid cancer in patients diagnosed with MSO is very rare and is more commonly encountered compared to distant ovarian metastasis from primary thyroid cancer [4, 11]. In the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry database, 8.8% of patients had a concomitant or subsequent thyroid cancer diagnosed, suggesting that evaluation of the thyroid gland is important for patients diagnosed with MSO. In our case, the patient had bilateral thyroid nodules investigated through FNA. Final histology confirmed a synchronous primary thyroid papillary carcinoma. Imaging, laboratory findings, and examination and comparison of the histologic appearance of the specimen from both the ovary and thyroid may distinguish between synchronous tumors. Genetic studies including mutations in BRAF and RAS may also point to metastasis from MSO.

Management options are based largely on case studies, with no general consensus as to date. Options include conservative surgery for fertility preservation and definitive surgery with full staging [5, 7]. These include ovarian cystectomy, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (USO), BSO, total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAHBSO), and debulking surgery. In the presence of gross metastasis, or for those who have completed childbearing, full surgical staging is recommended [5, 7]. In the younger patients who desire fertility preservation, and with less apparent disease or those confined to the ovary, conservative surgery may be offered. However, the study by Ayhan et al reported a statistically significant difference in progression-free survival (PFS) in those undergoing conservative and definitive surgery [4]. They have suggested discussing completion surgery once the patient completes childbearing, especially if high-risk prognostic factors are present. In our case, the patient had no desire for future childbearing, and given the nature of the disease on imaging, the patient underwent definitive surgery with TAHBSO, excision of all visible tumor implants, omentectomy, and nodal debulking.

Postoperative treatment of MSO may be based on treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer. High-risk lesions are those measuring > 4 cm, have local or distant invasion, have a BRAF mutation, or have a histology other than classic papillary cancer [12]. High-risk lesions have a higher risk of recurrence, and in these cases, total thyroidectomy followed by RAI therapy and thyroid suppression is recommended. The rationale for total thyroidectomy includes confirmation of the diagnosis of MSO by excluding ovarian metastasis of primary thyroid carcinoma and increasing the effectiveness of RAI by allowing preferential uptake in residual struma or metastasis. Studies conducted by DeSimone et al and Shrimali et al reported no recurrences in patients who underwent postoperative thyroidectomy followed by RAI [1, 8, 13]. It is suggested that postoperative thyroidectomy and RAI may be associated with a lower risk of disease failure and improvement of PFS [5, 13]. Since the patient also had a suspicious thyroid nodule, she later on underwent total thyroidectomy and RAI therapy. The decision for RAI was largely based on the high-risk features of her disease with tumor size > 4 cm, extraovarian metastasis, and non-papillary type carcinoma. The recurrence rate according to the study by Li et al of 120 cases of MSO was 21.8%, which was similar to the result published by DeSimone et al, with an overall recurrence rate of 35% in 24 patients [5, 13].

Close monitoring and surveillance are warranted in patients diagnosed with MSO, though the disease may behave indolently. There is no established follow-up recommendation for MSO patients, but serum TG, concomitant assessment of serum TG antibody (TGAb), and imaging are useful for monitoring disease. It has been recommended by Li et al that all patients with MSO should have serum TG and TGAb assessments every 6 - 12 months, similar to guidelines for thyroid cancer, and pelvic imaging with MRI performed every 1 - 2 years to check for disease recurrence [3, 5]. In this case, CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was chosen, since previous scans were able to pick-up the disease. Monitoring for MSO is also recommended for at least 20 years. This is due to the findings of their study that the median time to recurrence was 14 years, and several cases of late recurrences have been reported in literature [5].

Conclusions

MSO is a rare and complex ovarian tumor requiring high clinical suspicion for diagnosis in cases of ovarian masses. MSO can rarely present with concurrent papillary thyroid cancer. Multidisciplinary management involving gynecologists, endocrinologists, pathologists, and nuclear medicine specialists can be involved for optimal patient care. Early intervention and thorough follow-up are key to achieving long-term disease-free survival. Increased awareness and reporting of cases will enhance understanding and treatment of this rare condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chua Zhengyu Samuel for the assistance in acquiring the slides and images.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was secured from the patient.

Author Contributions

Angelica Stephanie K. Munoz: conceptualization (lead), writing - original draft (lead), formal analysis (lead), and writing - review and editing (equal). Jeffrey Jen Hui Low: conceptualization (supporting), review and editing (equal).

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

CT: computed tomography; MSO: malignant struma ovarii; CA-125: cancer antigen 125; ENT: ear, nose and throat; FNA: fine-needle aspiration; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; FDG PET: fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; USO: unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; BSO: bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TAHBSO: total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; RAI: radioactive iodine; PFS: progression-free survival; TG: thyroglobulin; TGAb: thyroglobulin antibody

| References | ▴Top |

- Willemse PH, Oosterhuis JW, Aalders JG, Piers DA, Sleijfer DT, Vermey A, Doorenbos H. Malignant struma ovarii treated by ovariectomy, thyroidectomy, and 131I administration. Cancer. 1987;60(2):178-182.

doi pubmed - Kondi-Pafiti A, Mavrigiannaki P, Grigoriadis C, Kontogianni-Katsarou K, Mellou A, Kleanthis CK, Liapis A. Monodermal teratomas (struma ovarii). Clinicopathological characteristics of 11 cases and literature review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32(6):657-659.

pubmed - Yoo SC, Chang KH, Lyu MO, Chang SJ, Ryu HS, Kim HS. Clinical characteristics of struma ovarii. J Gynecol Oncol. 2008;19(2):135-138.

doi pubmed - Ayhan S, Kilic F, Ersak B, Aytekin O, Akar S, Turkmen O, Akgul G, et al. Malignant struma ovarii: From case to analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(9):3339-3351.

doi pubmed - Li S, Hong R, Yin M, Zhang T, Zhang X, Yang J. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and survival outcomes of ovarian strumal diseases: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):497.

doi pubmed - Hanby AM, Walker C, Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. Pathology and genetics: tumours of the breast and female genital organs. WHO Classification of Tumours series - volume IV. Lyon, France: IARC Press. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:133.

doi - Goffredo P, Sawka AM, Pura J, Adam MA, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Malignant struma ovarii: a population-level analysis of a large series of 68 patients. Thyroid. 2015;25(2):211-215.

doi pubmed - Shrimali RK, Shaikh G, Reed NS. Malignant struma ovarii: the west of Scotland experience and review of literature with focus on postoperative management. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012;56(4):478-482.

doi pubmed - Cui Y, Yao J, Wang S, Zhao J, Dong J, Liao L. The clinical and pathological characteristics of malignant struma ovarii: an analysis of 144 published patients. Front Oncol. 2021;11:645156.

doi pubmed - Fujiwara S, Tsuyoshi H, Nishimura T, Takahashi N, Yoshida Y. Precise preoperative diagnosis of struma ovarii with pseudo-Meigs' syndrome mimicking ovarian cancer with the combination of (131)I scintigraphy and (18)F-FDG PET: case report and review of the literature. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11(1):11.

doi pubmed - Seo GT, Minkowitz J, Kapustin DA, Fan J, Minkowitz G, Minkowitz M, Dowling E, et al. Synchronous thyroid cancer and malignant struma ovarii: concordant mutations and microRNA profile, discordant loss of heterozygosity loci. Diagn Pathol. 2023;18(1):47.

doi pubmed - Chaidarun T, Sorensen M, Chaidarun S. ODP493 malignant struma ovarii with papillary thyroid carcinoma and concomitant high risk thyroid nodule. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6(Supplement_1):A771. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jes/article-pdf/6/Supplement_1/A771/47383921/bvac150.1593.pdf.

- DeSimone CP, Lele SM, Modesitt SC. Malignant struma ovarii: a case report and analysis of cases reported in the literature with focus on survival and I131 therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89(3):543-548.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.