| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, March 2025, pages 000-000

A Tubo-Ovarian Abscess Caused by Salmonella enterica

Natalia Karatzanoua, f, Maria Koukoumeloua, Sofia Michalakia, Evgenia Efthymioub, Nikolaos Machairiotisc, Dimos Sioutisc, Dimitrios Panagiotopoulosd, Chrysi Christodoulakie, Periklis Panagopoulosc

aDepartment of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Goudi, Athens, Greece

bSecond Department of Radiology, Attikon University Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Rimini, Haidari 12462, Athens, Greece

cThird Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Attikon University Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Rimini, Athens, Greece

dDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, General Hospital of Messinia, Kalamata, Greece

eDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, General Hospital of Chania “St George”, Chania, Greece

fCorresponding Author: Natalia Karatzanou, Department of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Manuscript submitted December 17, 2024, accepted March 12, 2025, published online March 25, 2025

Short title: Tubo-Ovarian Abscess by Salmonella

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1023

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) is a serious complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is usually associated with polymicrobial infections, with a predominance of anaerobic bacteria. Salmonella species are rarely associated with TOA, as only 11 cases have been documented in the literature. We present the case of an 18-year-old virgin who contracted a Salmonella enterica (S. enterica)-induced TOA. After experiencing an episode of gastroenteritis 13 days earlier, attributed to chicken consumption, the patient revealed severe abdominal pain, fever, diarrhea and vomiting. A right adnexal mass was found by imaging, and symptoms continued even after starting broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment. For this reason, an exploratory laparotomy was considered crucial, and it confirmed a right TOA, necessitating surgical management, including a right salpingectomy and abscess drainage. Postoperative cultures identified S. enterica as the causative organism. The patient recovered uneventfully after targeted antibiotic therapy. A Salmonella-associated TOA was observed in a non-sexually active patient, with the most probable route of transmission being an ascending infection following recent gastroenteritis. No underlying gynecological pathology was found. Since unspecific symptoms of TOA might imitate those of other acute abdominal disorders, this article emphasizes the difficulties in diagnosing this pathology in sexually inactive patients. Including rare pathogens such as Salmonella species in the differential diagnosis of TOA is essential. Early recognition, combined with appropriate surgical treatment, is critical for a successful outcome if conservative management fails.

Keywords: Tubo-ovarian abscess; Salmonella; Case report; Virgin; Exploratory laparotomy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) is a complex infectious adnexal mass that typically arises as a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). These abscesses are often polymicrobial, with anaerobic bacteria being the predominant pathogens [1].

While Salmonella is a gram-negative bacterium widely known as a major cause of gastroenteritis worldwide, its involvement in TOA is exceedingly rare [2, 3]. To date, only 11 cases of Salmonella-associated TOA have been documented in the literature [3-13]. This article aims to present the case of an 18-year-old virgin diagnosed with a TOA caused by Salmonella enterica (S. enterica). The case is analyzed in detail, hence providing insights into the clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of this rare condition.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

An 18-year-old female presented to our Emergency Department with acute onset of abdominal pain, accompanied by four episodes of vomiting, one episode of diarrhea, and a single episode of fever with chills within 24 h prior to admission. Her medical history included a recent episode of gastroenteritis 13 days prior to admission, attributed to chicken consumption. The symptoms, consisting of two episodes of diarrhea, one episode of vomiting, and dizziness, lasted for 1 day and resolved quickly after self-treatment with loperamide, famotidine and domperidone. On our clinical examination, the patient exhibited a mildly rigid abdomen with diffuse tenderness, a positive Murphy’s sign, and rebound tenderness. A vaginal examination was deferred as the patient reported virginity.

Diagnosis

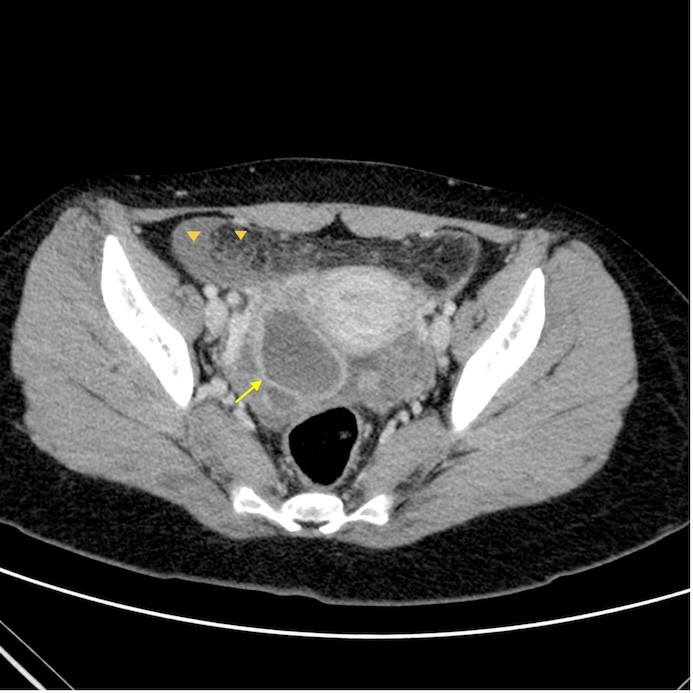

Her vital signs were stable, and she had an elevated body temperature of 38.6 °C. Initial laboratory investigations revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell (WBC) count of 21,560/µL and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 134 mg/L. An urgent abdominal ultrasound revealed a distended appendix measuring 7.4 mm in diameter. Gynecological ultrasonography identified a cystic adnexal mass measuring 67 × 61 × 47 mm, characterized by mixed echogenicity. To further evaluate the findings, an emergency contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed. CT of the lower abdomen revealed a cystic hypodense lesion on the right side of the pelvis with a thick enhancing wall. Fat stranding and free fluid were also present (Fig. 1). These imaging features were consistent with PID, a right adnexal lesion, and secondary inflammatory changes involving the appendix, small bowel, and colon. Additionally, vaginal fluid and blood cultures were obtained.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Axial post-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen shows a cystic lesion in the right adnexa (arrow) with a thick enhancing wall. Fat stranding and free fluid are also present (arrowheads). |

Treatment

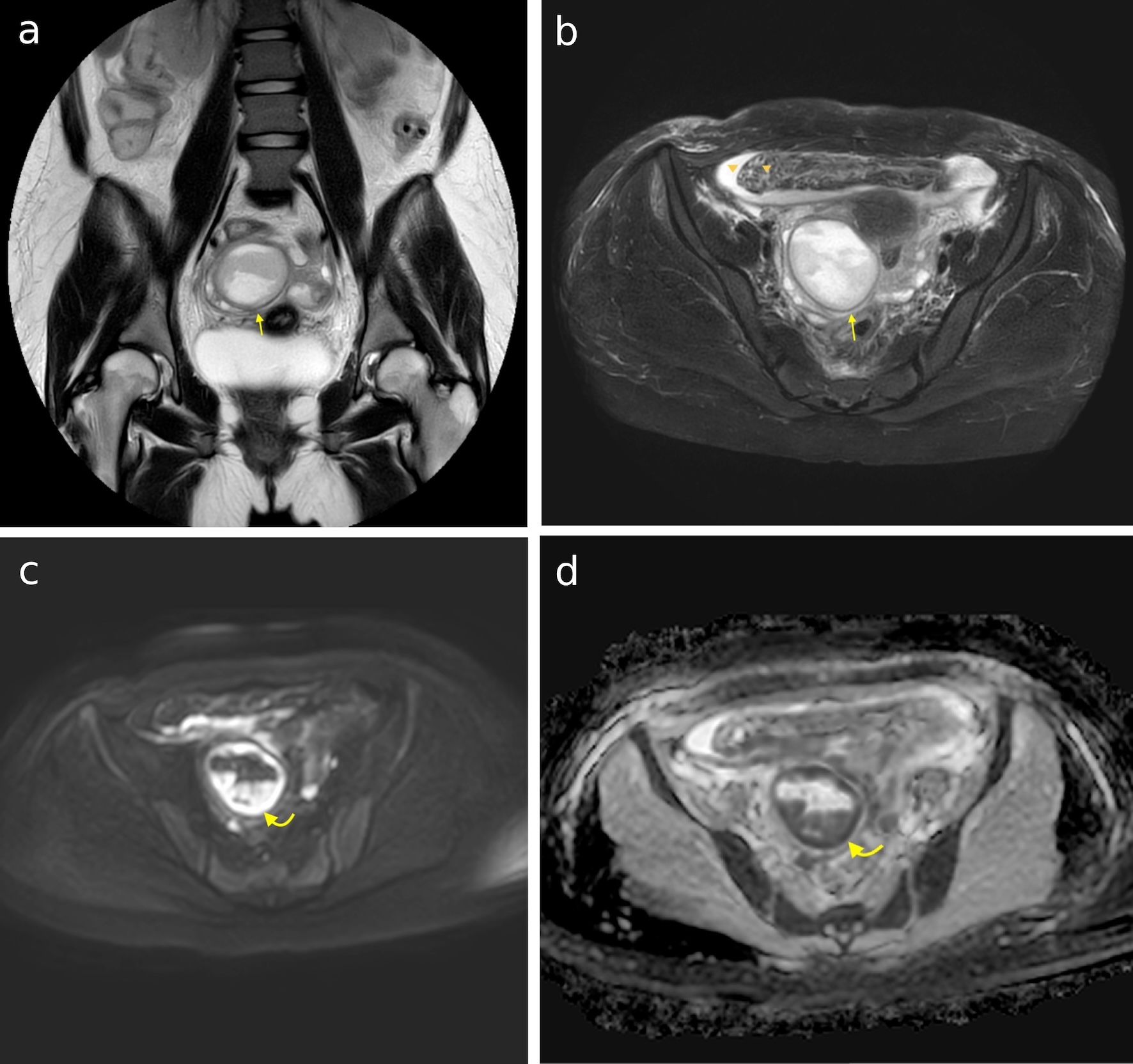

The patient was admitted to the hospital and initiated on broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy consisting of cefoxitin 2 g three times daily intravenously (IV), metronidazole 500 mg twice daily IV, and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily orally. Painkillers, antiemetics and antipyretics were administered as needed, using tramadol, ondansetron and paracetamol. During hospitalization, the patient remained hemodynamically stable. Her clinical course was characterized by persistent abdominal pain localized to the epigastric region, periumbilical area, and right hypochondrium, initially intense and later becoming milder. She also experienced two episodes of diarrhea that lasted 2 days, one to three episodes of vomiting per day, and a fever once or twice daily, ranging from 38 °C to 39 °C, which was alleviated with paracetamol. A daily complete blood count and biochemical tests, including electrolytes, coagulation profiles and inflammatory markers, were performed almost daily throughout the hospitalization. The results revealed elevated inflammatory markers, with an initial CRP of 277 mg/dL and an increase in WBCs, which later showed slight improvement with the administration of antibiotics. For diagnostic workup and laboratory evaluation, a panel of tests was conducted, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) testing, serum human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), thyroid function tests, upright abdominal radiography, upper and lower abdominal ultrasonography, urinalysis, B-Koch urine culture, stool parasitological examination, stool culture for Clostridium species pluralis (spp.), and stool analysis for the detection of toxins A, B and C. All cultures were sterile, and no other pathological findings were observed. Due to mild inflammatory marker elevation and persistent symptoms despite antibiotics, cefoxitin was discontinued, and ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily was initiated, along with the previous antibiotic regimens. Blood cultures obtained at the Emergency Department were negative, and vaginal fluid cultures revealed the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis. Following the modification in antibiotic therapy, the patient showed no significant clinical improvement, with persistent one to two episodes of vomiting per day and febrile episodes once or twice daily, ranging between 38 °C and 38.6 °C. Diagnostic evaluation continued with a repeat gynecological ultrasound, which revealed no new findings or improvement in the pre-existing condition. Urine cultures were performed using Ziehl-Neelsen staining, auramine-rhodamine, BACTEC MGIT, Loewenstein-Jensen, and Myco/F Lytic bottle methods. An interferon-gamma release assay blood test was also conducted, alongside serological testing for hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL). All tests returned negative for detectable pathogens. Given the ongoing febrile episodes, the antibiotic regimen was altered to Tazocin 4.5 g four times a day, and doxycycline was continued. Subsequently, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed. The imaging clearly depicted the complex cystic lesion, with heterogenous signal intensity on T1 and T2 sequences, displacing the right adnexa inferiorly. The lesion showed areas of restricted diffusion, high signal in diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and low signal in an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, findings concomitant with abscess formation (Fig. 2). Due to persistent symptoms, blood cultures were obtained, which were negative. Following a surgical consultation, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. Prior to surgery, she was under antibiotic treatment with Tazocin 4.5 g four times daily IV and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily orally. She also received 2,500 IU of bemiparin and 40 mg of omeprazole IV before the procedure. The patient was kept nil per os for 1 day prior to surgery. Intraoperatively, a right TOA was identified, for which a right salpingectomy and removal of the abscess wall were performed. Associated pelvic fluid collections were drained, and specimens were sent for comprehensive microbiological and molecular analysis, including cultures for bacterial pathogens, mycobacteria, fungi, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a) Coronal T2-weighted image of the abdomen shows a highly heterogeneous complex cystic lesion in the right side of the pelvis (arrow). (b) Axial T2-weighted fat-saturated image shows a large complex cystic lesion in the right side of the pelvis (arrow), displacing the right adnexa inferiorly. Fat stranding and free fluid are also present (arrowheads). (c) Axial DWI image at b = 1,000 s/mm2, showing areas of high signal intensity within the lesion (curved arrow). (d) Same areas depict low signal in the ADC map corresponding to areas of restricted diffusion (curved arrow). DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient. |

Follow-up and outcomes

Postoperatively, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and afebrile, with an uneventful recovery. Cytological examination of the pelvic abscess fluid and peritoneal fluid revealed findings consistent with acute inflammation, with no evidence of malignancy. Histological analysis of tissue samples from the pelvic abscess, right fallopian tube, and the wall of the ovarian abscess demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation, with no evidence of malignancy. Molecular investigation was performed on cytological material obtained from the pelvic abscess fluid using real-time multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR), targeting STI markers such as Ureaplasma parvum, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Trichomonas vaginalis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Candida species, which returned negative for tested pathogens. Peritoneal fluid cultures were also conducted using Gram staining, aerobic and anaerobic cultures, as well as agar cultures for fungi, all of which returned negative results. Pus cultures were performed for anaerobic, fungal, and mycobacterial organisms, all of which yielded negative results. However, aerobic culture on MacConkey agar identified Salmonella spp. Further, PCR and serotyping using slide agglutination were obtained to reveal S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted on the S. enteritidis isolate from the patient’s clinical sample using the disk diffusion technique to determine the susceptibility to a panel of antibiotics. The isolate was susceptible to all antibiotics tested, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) well below the resistance threshold. Following infectious disease consultation, the patient was prescribed ceftriaxone 2 g IV for 7 days, followed by oral ciprofloxacin 600 mg twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg three times daily for 7 days. A follow-up evaluation was scheduled for 10 days post-treatment, and it was uneventful.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The presented case adds to the literature on TOA due to Salmonella, with 11 similar cases identified through a review using the keywords “tubo-ovarian abscess” and “Salmonella” [3-13]. In this report, we describe a case of a right TOA caused by S. enterica in an 18-year-old female with no history of sexual intercourse. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second such case involving a sexually inactive patient, the first being a 42-year-old female reported by Yakupogullari et al in 2019 [13].

Potential routes of transmission include lymphatic or hematogenous spread following bacteremia, ascending infection from the lower genital tract, or local spread from an infected adjacent organ such as the appendix or small intestine [3, 7, 13]. Regarding our patient, the most likely route of transmission must be through ascending infection from contaminated stool, following the episodes of diarrhea 13 days prior to admission, attributed to chicken consumption.

According to previously reported cases, most of the patients had an underlying gynecologic condition, suggesting that pre-existing pathology predisposes to localized Salmonella infection, either known prior to diagnosis or incidentally discovered during evaluation [14]. Endometrioma and endometriotic cysts were the most common underlying conditions, reported in five cases of TOA due to Salmonella by Ghose et al [4], Kostiala et al [5], Thaneemalai et al [6], Manning et al [8], Kudesia et al [10]. Additionally, Selvam et al [12] reported one case associated with a pre-existing dermoid cyst [12]. It should be noted that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or immunocompromised patients can present with an increased risk of developing localized infections following invasive salmonellosis [11, 14, 15]. Furthermore, there has been a case of adnexal abscess in a female patient who was a potential gastrointestinal Salmonella carrier following in vitro fertilization (IVF). In that case, it was hypothesized that the oocyte collection needle was contaminated during a possible stick injury to the bowel [13]. Notably, in our patient and the 47-year-old female reported by Valayatham et al [9], no visible ovarian abnormalities or pre-existing disease were identified.

TOA in young, sexually inactive girls poses a diagnostic challenge. The rarity of Salmonella-induced TOAs often leads to a lower index of suspicion, contributing to diagnostic delays [3, 16]. As noted in previous cases, this rare condition can mimic ovarian cysts, tumors, or acute abdomen [12, 14-17]. In our case, the patient’s presentation with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever and gastrointestinal disturbances, coupled with the absence of typical risk factors for PID, further obscured the clinical picture. In the current case, it was only upon surgical exploration and subsequent microbiological analysis that Salmonella was identified as the causative pathogen. This underscores the importance for clinicians to maintain a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating pelvic masses, especially in patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms, and to consider uncommon pathogens like Salmonella within the etiological spectrum of TOAs [15]. Laboratory diagnosis of Salmonella-induced TOAs primarily relies on the isolation of the organism from abscess fluid or tissue samples. Culture techniques remain the gold standard, with growth typically observed on selective media such as MacConkey agar. In our case, pelvic fluid collections were aspirated, and samples were submitted for comprehensive microbiological and molecular testing, including cultures for bacterial pathogens, mycobacteria, fungi, and STIs. Histopathological examination might reveal features such as hemorrhagic and degenerative changes within the cyst wall, often associated with endometriotic tissue, as noted in similar case reports. Serological tests and stool cultures can provide valuable information regarding concurrent or preceding enteric infections, providing additional context for the diagnosis [3].

In our case, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was initiated, comprising cefoxitin, metronidazole, and doxycycline. Successful conservative management with antibiotics alone has not been described in the literature. Surgical removal of the infected abscess has been deemed necessary for all previously reported cases of TOA due to Salmonella [3-13]. All 11 reported cases of TOA due to Salmonella have been treated after laparotomy or laparoscopy, including our case. However, while antibiotics remain the first-line treatment for TOAs, unsuccessful cases should proceed to drainage under ultrasound guidance or surgical intervention [12]. Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be initiated promptly, targeting both typical pelvic pathogens and Salmonella species. Following culture and sensitivity results, antibiotic regimens can be tailored accordingly. The most widely used and effective protocols include a combination of clindamycin, gentamicin, and ampicillin; cephalosporin with gentamicin and metronidazole; or cephalosporin combined with metronidazole. Surgical management is considered in patients who do not respond to antibiotic therapy within 72 h, present with large abscesses, or exhibit signs of rupture or sepsis. Procedures range from minimally invasive techniques, such as image-guided percutaneous drainage, to more extensive surgeries like laparoscopic or open salpingo-oophorectomy. The type of procedure depends on factors such as abscess size, patient stability, and reproductive considerations. Early and aggressive treatment is crucial to prevent complications such as abscess rupture, peritonitis, and sepsis, thereby preserving reproductive function and reducing morbidity [17].

Learning points

The diagnostic complexity of TOA caused by Salmonella lies in its ability to mimic other acute abdominal pathologies, such as ovarian cysts, tumors, or appendicitis, particularly in patients without a history of sexual activity or pre-existing gynecologic conditions. Our findings emphasize the importance of considering Salmonella as a potential causative pathogen in TOAs, even in atypical clinical presentations. Despite the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics as initial therapy, surgical intervention remains a cornerstone of effective treatment, as demonstrated by previously reported cases, including this one. This case highlights the need for heightened clinical suspicion, thorough history-taking, and a multidisciplinary approach for timely diagnosis and management of this rare but significant condition.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

NK, MK and SM observed the patient. EE performed a radiology consultation. PP observed the patient and performed medical treatment. NK, MK and SM drafted, reviewed and edited the manuscript. PP and NM reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have approved the final article for journal publication.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

TOA: tubo-ovarian abscess; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; STIs: sexually transmitted infections; WBC: white blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; IV: intravenously; IVF: in vitro fertilization; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient; MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration

| References | ▴Top |

- Gungorduk K, Guzel E, Asicioglu O, Yildirim G, Ataser G, Ark C, Gulova SS, et al. Experience of tubo-ovarian abscess in western Turkey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124(1):45-50.

doi pubmed - Chaudhari R, Singh K, Kodgire P. Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella spp. Res Microbiol. 2023;174(1-2):103985.

doi pubmed - Sharma P, Bhuju A, Tuladhar R, Parry CM, Basnyat B. Tubo-ovarian abscess infected by Salmonella typhi. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr-2017-221213.

doi pubmed - Ghose AR, Vella EJ, Begg HB. Bilateral salmonella salpingo-oophoritis. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62(725):227-228.

doi pubmed - Kostiala AA, Ranta T. Pelvic inflammatory disease caused by Salmonella panama and its treatment with ciprofloxacin. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96(1):120-122.

doi pubmed - Thaneemalai J, Asma H, Savithri DP. Salmonella tuboovarian abscess. Med J Malaysia. 2007;62(5):422-423.

pubmed - Kaur J, Kaistha N, Gupta V, Goyal P, Chander J. Bilateral tuboovarian abscess due to salmonella paratyphi A. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. 2008;16(6):408-410.

- Manning S, Saridogan E. Tubo-ovarian abscess: an unusual route of acquisition. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29(4):355-356.

doi pubmed - Valayatham V. Salmonella: the pelvic masquerader. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(2):e53-55.

doi pubmed - Kudesia R, Gupta D. Pelvic Salmonella infection masquerading as gynecologic malignancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 2):475-477.

doi pubmed - Guler S, Oksuz H, Cetin GY, Kokoglu OF. Bilateral tubo-ovarian abscess and sepsis caused by Salmonella in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013200187.

doi pubmed - Selvam EM, Sridevi TA, Menon M, Rajalakshmi V, Priya RL. A case of salmonella enterica serovar typhi Tubo ovarian abscess. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2015;65(4):278-280.

doi pubmed - Yakupogullari Y, Isik B, Gursoy NC, Bayindir Y, Otlu B. Case of Tubo-ovarian abscess due to salmonella enterica following an in vitro fertilization attempt. Mediterranean Journal of Infection Microbes and Antimicrobials. 2019.

- Gorisek NM, Oreskovic S, But I. Salmonella ovarian abscess in young girl presented as acute abdomen—case report. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(1):223-225.

pubmed - Getahun SA, Limaono J, Ligaitukana R, Cabenatabua O, Soqo V, Diege R, Mua M. Ovarian abscess caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):303.

doi pubmed - Kairys N, Roepke C. Tubo-ovarian abscess. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Chiva LM, Ergeneli M, Santisteban J. Salmonella abscess of the ovary. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1 Pt 1):215-216.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.