| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Review

Volume 15, Number 1, March 2026, pages 1-12

Seasonal Variation in Maternal Vitamin D Levels on Neonatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review

Natalie Aguilara , Sara Elliasa, b

, Allison Rakowskia

, Morgan Schafera

aCentral Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant, MI 48859, USA

bCorresponding Author: Sara Ellias, Central Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant, MI 48859, USA

Manuscript submitted November 20, 2025, accepted January 24, 2026, published online February 7, 2026

Short title: Seasonal Maternal Vit. D on Neonatal Outcomes

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1598

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Emerging evidence suggests that inadequate vitamin D levels in pregnant mothers can adversely affect fetal development, pregnancy outcomes, and maternal health. This systematic review analyzes current research to gain a better understanding of the association between seasonal variation in maternal vitamin D levels and differing, potentially adverse, fetal outcomes. A systematic search was conducted across four databases; combinations of keywords and/or MeSH guided the literature search, yielding 1,852 articles that were screened and included if the study focused on seasonal variation in maternal vitamin D levels with associated neonatal outcomes. Full text review was performed by four reviewers on 39 articles, yielding a finalized total of 11 articles. The results of this systematic review supported that, across a vast array of geographic locations, vitamin D levels in pregnant women were, on average, consistently highest during the summer and lowest in the winter. However, the relationships between maternal vitamin D status and select neonatal outcomes including small for gestational age (SGA), preterm birth, and low birth weight were inconsistent. These discrepancies most likely result from external factors including geographic latitude and resulting sun exposure, limited supplementation, cultural conventions, and maternal demographics. Additionally healthcare access and public health policies cannot be overlooked; thus, vitamin D deficiency amongst pregnant women, especially in areas with limited sun exposure, needs to be prioritized and addressed via clinician intervention and public health services and programs, and further research is needed to refine these protocols to reduce global vitamin D deficiency and its associated, potentially adverse, outcomes.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Vitamin D; Infant; Newborn; Seasons; Premature birth; Birth weight; Birth length

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The timing of pregnancy within the calendar year can have profound implications for neonatal outcomes, as environmental and biological factors fluctuate with the seasons [1]. Seasonal changes influence various maternal physiological conditions, including nutrient availability, exposure to pathogens, and physical activity levels, all of which can affect fetal development [2, 3]. Research has demonstrated that the season of conception or delivery may correlate with variations in birth weight, preterm birth rates, and other neonatal outcomes [4]. Among these factors, vitamin D status, which depends heavily on sunlight exposure, is particularly noteworthy.

Vitamin D, a critical fat-soluble vitamin, plays an essential role in calcium homeostasis, bone health, immune function, and cellular growth. Its synthesis is stimulated by ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from sunlight, with some contributions from dietary sources [5]. Consequently, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, or 25(OH)D, levels fluctuate significantly depending on the season, latitude, and individual sun exposure [6]. These variations can have profound physiological implications, particularly for pregnant individuals, as vitamin D is vital for both maternal and fetal health [7]. This has led to the inclusion of vitamin D in prenatal vitamins, yet many pregnant women continue to experience deficiency [8].

Emerging evidence suggests that maternal vitamin D insufficiency can adversely affect fetal development. A meta-analysis examining neonatal outcomes among mothers receiving vitamin D supplementation found significant results for increased weight and length of the neonate when compared to women deficient in vitamin D [9]. Recent literature also suggests possible associations between maternal vitamin D depletion and increased risks of pregnancy losses, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, maternal infections, and preterm births [7]. Although more randomized trials are needed to determine the extent of vitamin D supplementation on neonatal outcomes, it is evident that vitamin D deficiency can adversely affect both pregnant women and their fetuses. It is standard of care to give vitamin D supplementation to pregnant and lactating women, through prenatal supplements and beyond. However, dosage of the supplementation is another debate entirely.

The current systematic review aimed to analyze current research on seasonal variations in vitamin D levels among pregnant women and examined how these fluctuations may have contributed to differences in neonatal outcomes. There is established research to suggest that season of birth affects birth outcomes as well as scientific evidence to indicate that seasonal exposure to sunlight impacts vitamin D levels. This systematic review aimed to investigate this understanding further by evaluating the association between seasonal differences in maternal vitamin D levels being significant enough to lead to differing, potentially adverse, neonatal outcomes. Understanding the interplay between seasonal vitamin D variability and neonatal outcomes is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate risks and improve maternal and child health, both in the USA and across various global climates.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Search strategy

For this systematic literature review, a comprehensive search of relevant literature was performed in May of 2024, across four databases. The search utilized a combination of keywords and/or Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term following review with a medical librarian, to ensure a thorough and proper review. The search strategy focused on the key search terms “pregnancy,” “vitamin D,” and “season” along with their associated MeSH terms, as listed in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Database Search Strategy for Keywords and MeSH Terms (PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Scopus) |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

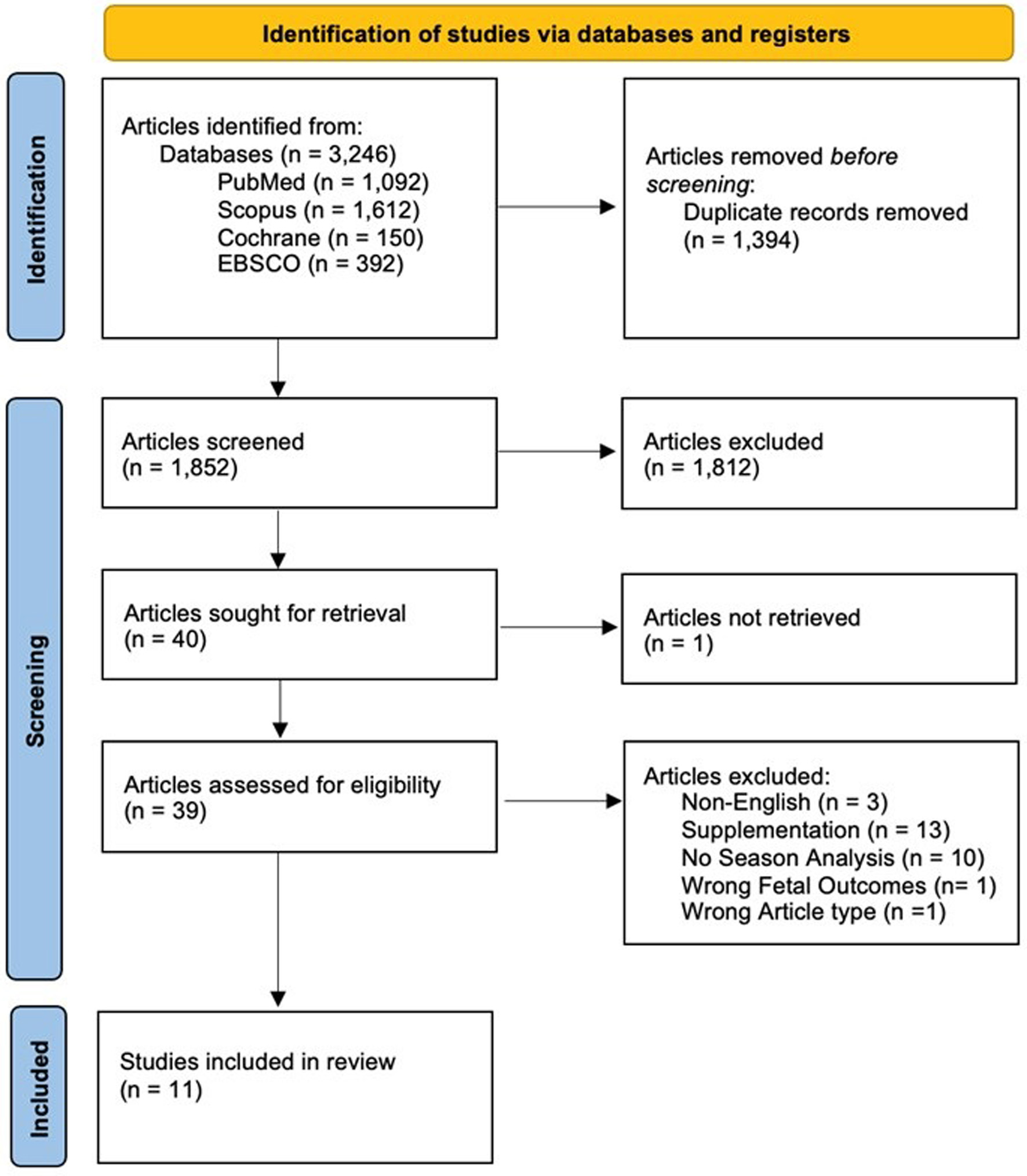

Articles that satisfied all our PICO(T) search criteria were included in our study. The PICOT strategy used for the systematic review was as follows: population: pregnant women with serum 25(OH)D concentrations measured during pregnancy who did not explicitly consume vitamin D supplements, interventions: the pregnancies of these women that occurred in the winter season, comparison: the pregnancies of these women that occurred in the summer season, outcome: evaluates differences in neonatal pregnancy outcomes between these two groups. Articles that assessed maternal vitamin D levels, the season or time of year that vitamin D levels were obtained, and at least one adverse neonatal outcome were included. Maternal vitamin D levels were determined through quantitative laboratory data that categorize vitamin D levels on standard guidelines or qualitative descriptors such as “high, low, sufficient, insufficient, adequate or hypovitaminosis,” as determined by each author’s guidelines for each study. Seasons were defined as “spring, summer, fall, winter” based on local criteria specific to the data source, with individual months used as a descriptor for timing of year. Adverse neonatal outcomes were used to aid in reflecting the impact of maternal vitamin D levels throughout pregnancy and may include abnormal birth weight (low or SGA), preterm birth (being less than 37 weeks’ gestation), birth length, or head circumference. Studies were excluded if they did not include prenatal maternal vitamin D levels, had no assessment of adverse neonatal outcomes, if mothers in the study received vitamin D supplementation outside of prenatal vitamins or multivitamin use, were a non-English study, were a non-human study, or were a systematic review or editorial letter. The PRISMA diagram outlining the article selection process of our systematic review can be found in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The PRISMA diagram outlining the article selection process of our systematic review. |

Study selection

Rayyan [10] software was utilized for the screening process. After duplicate articles were resolved from the four database searches, a preliminary screen of the articles was conducted, with each article abstract being screened by at least two individual authors via a blind review to reduce bias. All reviewers followed the same inclusions/exclusion criteria described above. All conflicts on inclusion/exclusion of articles were discussed and resolved through discussion among all reviewers. The abstracts included were exported in a Microsoft Excel file for data extraction in a full-text screening using the same inclusion/exclusion criteria used in the preliminary screening. The full-text articles were analyzed by one reviewer that examined whether the article qualified for inclusion by thoroughly reviewing the study design, population, and relevant outcomes of the article. To ensure a thorough review of each article, all included articles were analyzed a second time by another reviewer. All four reviewers discussed any discrepancies on whether an article was to be included or excluded following full-text analysis.

Data extraction

After a thorough review, 11 articles were selected for inclusion in the final analysis of this systematic review. Data were manually and systematically extracted from each of the selected articles by the four authors. The extracted data included the following variables: study title, authorship, study design, year of publication, location of study, season of measurement, vitamin D status, and associated adverse neonatal outcomes such as vitamin D deficiency, preterm birth, birth weight, birth length, and head circumference. The articles were evenly distributed among the four authors for primary data extraction. Subsequently, a second author was assigned to independently review the extracted data to identify any inconsistencies or discrepancies. Any discrepancies were discussed by the four authors, and the initial author responsible for the extraction made the necessary revisions. The results of this data extraction process are summarized in Table 2 [11–21].

Click to view | Table 2. Study Characteristics and Article Identifiers [11–21] |

Assessment of risk of bias

To evaluate the risk of bias in each study included in the review, all articles were evaluated using the “Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool” (MMAT), Version 2018 in Table 3 [11–21]. This standardized tool is specifically designed to assess the risk of bias in studies with diverse research designs within a single systematic review. Its structured framework allowed for a consistent and comprehensive appraisal, to enhance the reliability and validity of our findings. Each study was independently reviewed by two randomly assigned authors. Following the initial assessments, all four authors discussed any discrepancies and resolved conflicts through unanimous consensus. This collaborative approach strengthened the reliability and validity of the risk of bias assessment. The final assessments are presented in Table 3.

Click to view | Table 3. MMAT Assessment for Risk of Bias [11–21] |

| Results | ▴Top |

The search and screening for this systematic review, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1), identified 3,246 articles across four data bases: PubMed (n=1,092), CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCO) (n = 392), Cochrane Library (n = 150), and Scopus (n = 1,612). After removing 1,394 duplicate articles, 1,852 articles were screened by the authors. Articles were deemed eligible for inclusion if they focused on seasonal variation in maternal vitamin D levels and their association with neonatal outcomes. Of these, 39 articles were selected for full-text review. Following the guidelines of inclusion and exclusion based on the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1), 11 articles were selected for further analysis.

This systematic review identified 11 studies of various designs published between 2011 through 2020, with one outlier published in 1974. The studies were conducted in various geographic locations including Turkey, Slovenia, South Africa, the United States, China, Morrocco, Japan, South Korea, and Ireland. The sample sizes varied widely across each study, ranging from 60 to 34,417 pregnant women with a median of 229 women per study. Out of the 11 articles included, eight of the studies reported significant seasonal variation in vitamin D status, while six studies reported significant adverse neonatal outcomes associated with maternal vitamin D levels.

Seasonal variation of maternal vitamin D levels during pregnancy

Significant association between maternal vitamin D levels and seasonal variation

Eight of the 11 studies found a significant association between maternal vitamin D levels and seasonal variation (as shown in Table 4) [11–21]. One such study conducted in Ireland [11] found only 10% of women in the summer cohort to be vitamin D sufficient while 50% were at high risk of deficiency. In contrast, the winter cohort showed 67% sufficiency and 7% at high risk of deficiency (P < 0.05) in the first trimester. This trend continued at 28 weeks’ gestation, where 30% of the winter cohort had sufficient 25(OH)D concentrations compared to over 53% of the summer cohort (P < 0.05). However, by the time of delivery, vitamin D sufficiency sharply declined. In the winter cohort, 3% were sufficient and 47% were at high risk of deficiency. Similarly, in the summer cohort deliveries, although 25(OH)D concentrations were statistically significantly higher at 28 weeks, only 13% of samples were sufficient, and 43% were at high risk of deficiency at time of delivery. Concentrations of 25(OH)D were highest in mid-summer and lowest at the beginning of spring.

Click to view | Table 4. Data Extraction Results [11–21] |

In a study conducted in Slovenia [12], 25(OH)D was found to be statistically significant across different seasons, with prevalences of sufficiency at 12% in the summer, 2% in the autumn, 1% in the winter, and 13% in the spring (P < 0.001). The rest of the participants in each cohort were defined as being insufficient, deficient, or severely deficient. Notably, at the time of this study, the only nutritional supplement recommended nationally in Slovenia was folic acid.

A study conducted in Turkey [13] found that 86% of all pregnant women participating in the study had deficient vitamin D levels, 12% were inadequate, and 2% were sufficient. Serum 25(OH)D levels were lowest during the winter season and highest during the summer (P < 0.001) showing a significant association. This study also found that 10.95 ng/mL was the optimal cutoff value for vitamin D deficiency with an 82.5% sensitivity and 91.5% specificity.

A study conducted in Johannesburg, South Africa [14] found that mean levels of serum 25(OH)D were highest in summer and lowest in winter for their sample. The proportion of mothers with vitamin D deficiency increased from 7% during summer deliveries to 27% during winter deliveries. The study found that women were three times more likely to be vitamin D deficient if delivering during the winter, in contrast with the other seasons. Also mean 25(OH)D levels in summer almost doubled those in winter (82.9 vs. 41.8 nmol/L respectively). According to multiple regression analysis, the predictor of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women was delivering during winter (odds ratio (OR) 2.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.47–5.61; P < 0.001).

Another study conducted in Turkey [15] assessed the serum levels of 25(OH)D in the first trimester and found that 68.3% of the winter cohort were vitamin D deficient while only 31.7% of the summer cohort were deficient. The study found that serum 25(OH)D collected amongst pregnant women during summer months was significantly higher than the levels in winter months. Binary logistical regression analysis determined this difference to be statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

In a study conducted in China [16], results found that only 1.6% of the subjects had an adequate serum 25(OH)D levels (≥ 75 nmol/L). In contrast to the other studies, the highest vitamin D levels occurred in winter with a median serum 25(OH)D concentration of 45.10 nmol/L and the lowest vitamin D levels occurred in summer, with a median 25(OH)D concentration of 41.76 nmol/L. Both Kruskal-Wallis tests and Chi-square analysis of the relationship between serum 25(OH) D and seasons found them to be significant (P < 0.001, P < 0.001). However, a multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that season was correlated with 25(OH) D status, except for the season of summer. Compared with spring season, autumn and winter had lower risk of vitamin D deficiency with ORs of 0.841 and 0.607, respectively.

Two studies had mixed results where only certain seasons provided significant results. One such study in South Korea [17] found that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency varied significantly across seasons: 84.7% in the spring, 45.5% in the summer, 73.7% in the fall, and 100% in the winter. The serum 25(OH)D concentrations differed significantly between spring and summer, spring and fall, and summer and winter (P < 0.05). However, the difference in deficiency prevalence between summer and winter specifically was not significant, likely due to the small sample size of the winter cohort, as noted by the authors. A pooled analysis confirmed that vitamin D deficiency prevalence was significantly lower in the summer compared to both spring and fall (P < 0.05), with the highest risk observed in the spring (P < 0.05). Additionally, Hillman & Haddad (1974) [18] found a significant influence on serum 25(OH)D levels but only in the months of January and December. Overall, maternal levels were routinely lower in the winter season.

No significant association between maternal vitamin D levels and seasonal variation

Only three studies showed no significant association between vitamin D levels and seasonal variation (as shown in Table 4). The first study was conducted in Tokai, Japan [19], which showed that mean serum 25(OH)D levels were 13.9 ± 4.2 ng/mL in March, 14.3 ± 5.1 ng/mL in June, 15.7 ± 6.4 ng/mL in September, and 13.7 ± 5.1 ng/mL in December. While levels were lowest in winter and highest in summer, the variation was not statistically significant according to t-test analysis. Overall, hypovitaminosis D was revealed in 85 mothers (89.5%). Additionally, in a Morocco study [20], findings showed that 90.1% of pregnant women had hypovitaminosis D with an average concentration of 11.09 ± 5.91 µg/L, but there was no statistically significant difference in levels depending on season (P = 0.087).

Lastly, in Slovenia, Treiber et al [21] found that only 34% of mothers were classified as having sufficient vitamin D levels (> 50 nmol/L). There was seasonal variation with higher levels in September (74 ± 33 nmol/L) and June (60 ± 30 nmol/L) groups compared with the December (53 ± 27 nmol/L) and March (37 ± 23 nmol/L) groups. While the authors mentioned a significant seasonal effect on maternal 25(OH)D levels, there was no evidence of statistical analysis. Therefore, this association between season and serum 25(OH)D level cannot be statistically significant.

Vitamin D status and neonatal outcomes

Significant association between maternal vitamin D status and neonatal outcomes

Five of the 11 studies found significant associations between maternal vitamin D and various neonatal outcomes (as shown in Table 4). Dovnik et al [12] found significantly lower levels of 25(OH)D in women with preterm delivery (P < 0.022) compared to those without the complication through independent samples t-test analysis. Those who had preterm labor had an average 25(OH)D concentration of 30.8 ± 15.1 vs. 44.3 ± 24.0 nmol/L for those who did not go into labor preterm. Additionally, one study in Japan [19] found that serum 25(OH)D levels in mothers with threatened preterm delivery were lower than those in those with normal delivery. Serum 25(OH)D levels were 11 ± 3.2 ng/mL in mothers with threatened preterm delivery compared with those who did not (15.2 ± 5.1 ng/mL). Multiple regression statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA) found this association to be statistically significant (P = 0.023 and P = 0.002, respectively).

A study from Turkey [13] found that 25(OH)D levels in the winter cohort were a statistically significant predictor for preterm delivery and SGA (P = 0.000). This association held true when comparing these variables to women with below optimal levels of 25(OH) D (P = 0.000). Treiber et al [21] also found that preterm birth was associated with 25(OH)D concentrations (P < 0.001). Lastly, Hillman & Haddard [18] found a weak correlation between low maternal 25(OH)D levels and birth weight, but did not find maternal-cord level differences to be statistically significant with birth weight.

No significant association between maternal vitamin D status and neonatal outcomes

However, six out of the 11 studies did not find any significant associations between maternal vitamin D levels and neonatal outcomes (as shown in Table 4). Walsh et al [11] found that infants of mothers with 25(OH)D levels below the median in early pregnancy had shorter mean lengths (52.1 vs. 53.6 cm, P = 0.04). However, this relationship was not statistically significant at 28 weeks. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed between mothers with 25(OH)D levels above or below the median at any stage regarding other outcomes. Another study [17] investigated the association between preterm birth and SGA with vitamin D. Among women who delivered preterm babies, 77.8% were vitamin D deficient and among women with SGA babies, 62.5% were vitamin D deficient. Despite these findings, no significant associations were found between vitamin D deficiency and either preterm delivery or SGA outcomes according to univariate or multivariate logistic regression analyses. Similarly, the St. Louis Missouri study [18] found no significant difference in maternal serum 25(OH)D levels between those with term and premature births.

In a South African study [14], univariate and multivariate analysis also showed no significant correlation between vitamin D deficiency in mothers and preterm birth (P = 0.91, P = 0.156) or low birth weight (P = 0.148, P = 0.058). Treiber et al [21] in Slovenia found that there were no significant differences in neonate weight, length, head circumference, gestational age, or incidence in low birth weight between seasonal groups. Ates et al [15] reported that there were no significant correlations between serum 25(OH)D levels and numerical outcome variables including preterm delivery and birth weight, regardless of season (P = 0.99, P = 0.66 respectively) according to Yates-corrected Chi-squared analysis.

In a study conducted in Shanghai, China [16], there was no association found between maternal serum 25(OH)D levels and low birth weight according to logistic regression analysis (P = 0.706). Loudyi et al [20] found that the average birth weight for all the newborns for a cohort in Morocco was 3,337.9 ± 509 g, average height was 49.18 ± 3.3 cm, and average head circumference was 34.75 ± 2.2 cm. However, there was no statistical analysis done to determine the significance of these results. No correlation was found between maternal hypovitaminosis D and birth weight in the newborns involved in this study. Lastly, Treiber et al [21] found no relationship between any of the investigated neonatal anthropometric parameters at birth which included weight, length, and head circumference.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Maternal vitamin D status is a critical factor in pregnancy and neonatal health, with evidence highlighting the impact of vitamin D deficiency on birth outcomes [22]. Seasonal variations in maternal vitamin D levels have been consistently documented, with higher levels in the summer and lower levels in the winter, largely due to differences in sun exposure. These variations have raised concerns regarding the potential impact of vitamin D deficiency on neonatal outcomes, including SGA, preterm birth, and low birth weight [7, 9]. Given these concerns, this systematic review aimed to explore the association between seasonal variation in maternal vitamin D levels and neonatal health outcomes, considering factors such as geographic location, dietary intake, and cultural practices.

Significant variation in vitamin D levels among pregnant women is evident throughout different seasons, with the highest vitamin D levels occurring in the summer and lowest vitamin D levels occurring in the winter, on average. This pattern was consistent across a variety of geographic locations, including Europe, Asia, and Africa. Specifically, lower maternal serum levels of 25(OH)D were found in the winter months, and higher maternal serum levels of 25(OH)D were found in the summer months, likely attributed to greater sun exposure, a major source of vitamin D. These results align with most studies, such as Dovnik et al [12], which found that 12% of pregnant women were vitamin D sufficient in the summer versus only 1% sufficient in the winter. Similarly, Choi et al [17] found that women were 100% vitamin D deficient in the winter and 45.5% in the summer, although no significant difference in the prevalence of these deficiencies were found between the winter and summer months, possibly due to sampling error. Similarly, in Turkey [13], 86% of women were classified as deficient in the winter. Conversely, those who reside in areas with greater consistency in sunlight exposure throughout the year may experience a less pronounced seasonal decline in vitamin D levels, although deficiency is still apparent. For example, in Johannesburg, South Africa [14], which experiences consistent sunlight year-round due to its proximity to the equator, only 7% of women were deficient in the summer compared to 27% in the winter.

One possible explanation for these discrepancies arises from several factors varying across populations and studies. First, key contributors to vitamin D synthesis include amount of sun exposure and regional setting. Since sun exposure varies with the seasons, especially at northern latitudes, decreased exposure in the winter months will lead to decreased vitamin D synthesis, and therefore higher rates of deficiency are expected. In some regions, seasonal variation does not follow this expected pattern, suggesting the influence of additional factors, such as geographic location and cultural factors, on vitamin D levels. Li et al [16] found that the highest vitamin D levels occurred in winter as opposed to summer, potentially due to regional factors such as cloud cover during China’s plum rain season and cultural preferences for lighter skin, leading to extensive sunscreen use. A Morocco study [20] found no seasonal variation in vitamin D levels even though 90.1% of pregnant women were deficient. In another study [11], the winter cohort showed higher vitamin D sufficiency at the start of pregnancy (67% vs. 10% in the summer cohort); however, by the time of delivery, sufficiency had sharply declined in both cohorts. This timing pattern is also supported by studies that were outside of our inclusion criteria [23], which reported minimal seasonal differences in maternal vitamin D levels early in pregnancy, yet significantly lower levels among winter and spring deliveries when compared to summer and fall deliveries. When taken together, this may suggest that the timing of pregnancy and season of delivery may lead to associations between neonatal outcomes as vitamin D levels varied based on seasonality across several studies. These findings underscore that while seasonal variation is a key factor, maternal vitamin D status is impacted by the complex interplay of environmental, cultural, and behavioral influences.

Although seasonal variation significantly influences vitamin D levels, the impact of other factors, such as healthcare access, cultural practices, and public health policies, cannot be overlooked. Regions with public health campaigns encouraging vitamin D supplementation, such as the United States and Japan, may provide an explanation for the adequate vitamin D level in some women. However, despite these recommendations, vitamin D deficiency remains high in these countries, pointing towards potential issues such as inconsistent supplementation guideline adherence, individual dietary habits, or limited access to appropriate supplementation [24]. In contrast, in countries like Slovenia [12], there is limited vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy, which may contribute to higher deficiency rates among pregnant women. The study reported that, at that time, the only recommended supplement during pregnancy was folic acid. Whereas in China [16], where the guidelines regarding vitamin D supplementation throughout pregnancy are lacking, further contribution to the higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency may be attributed by these absent recommendations or supplementation protocols.

The last important consideration is maternal race, or skin pigmentation, as a possible explanation for variations in maternal vitamin D levels. While race was not addressed consistently across the studies included in the review, a few did consider race in their studies. Both Loudyi et al [20] and Hillman et al [18] found high levels of deficiency among women with darker skin tones. While this was not shown to be statistically significant in Loudyi et al, likely due to the high prevalence of deficiency in the study population overall, Hillman found statistically higher levels of deficiency among their black mother-baby pairs and the study addresses that the cause of this statistically significant finding is unknown, but they propose skin pigmentation, availability of effective solar radiation, and dietary differences as potential factors [18]. It is a known mechanism that the melanin found in darker skin tones filters UBV radiation which reduces the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to pre vitamin D3 in the skin, therefore reducing the amount of vitamin D synthesis overall [14, 25]. While this is an established connection, the effect that differences in skin pigmentation have on maternal vitamin D levels, and subsequently neonatal outcomes, remains to be determined and is beyond the scope of this paper.

While the association between seasonal variation and maternal vitamin D level is more consistent and straightforward, the impact of maternal vitamin D status on neonatal outcomes appears to be more variable and complex. For instance, Choi et al [17] found that low levels of vitamin D were associated with both SGA and preterm births, although no significant associations were reported, likely due to the small sample size. Similarly, Öcal et al [13] found that low levels of vitamin D were statistically significant predictors of SGA and preterm birth solely in the winter, and low vitamin D levels were associated with threatened preterm birth [12, 19]. These findings, however, were not consistently replicated. For example, Ates et al [15] found no significant relationship between vitamin D deficiency and birth outcomes such as preterm birth or low birth weight, despite observing clear variation in vitamin D levels. These inconsistencies may stem from confounding factors, variations in sample size, study design, and differences in the specific populations studied.

Neonatal health outcomes associated with maternal vitamin D deficiency include an increased risk for SGA, low birth weight, preterm birth, impaired skeletal development, and increased susceptibility to infectious diseases [26]. Vitamin D plays a key role in calcium homeostasis and fetal bone mineralization, where deficiency during pregnancy has been associated with neonatal rickets and suboptimal bone growth [27]. Additionally, some studies suggest an association between low maternal vitamin D levels and an increased risk of neonatal infections, respiratory distress syndrome, and impaired immune function, largely due to vitamin D’s role in modulating the immune system [28]. However, while multiple studies support this link between maternal vitamin D deficiency and adverse neonatal outcomes, some studies have failed to find consistent association between vitamin D status and associated complications, likely due to confounding variables influencing this relationship.

Beyond seasonal variations and several other factors complicating the relationship between maternal vitamin D levels and neonatal health, there are a host of additional components which may contribute to deficiencies in ways that are challenging to isolate and quantify. Pregnancy-related changes in vitamin D metabolism can alter levels of available 25(OH)D, exacerbating deficiency, especially during the third trimester when the demand for nutrients is heightened [29]. Women with higher body fat percentages are also at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency, as excess fat stores vitamin D, reducing its bioavailability and resulting in lower circulating levels [30]. Additionally, one study found that vitamin D deficiency is more common in disadvantaged areas, pointing to the fact that healthcare access and socioeconomic status are important modulators of vitamin D status, and may augment the risk of deficiency in these populations [31]. In these cases, heightened deficiency not only affects maternal health but also contributes to adverse neonatal health outcomes impacting infection susceptibility risk and anthropometric development.

How vitamin D deficiency and seasonally linked variations in vitamin D status might impact pregnancy outcomes has been explored in several prior investigations. However, there are emerging pathways that link vitamin D signaling with circadian rhythm biology and alternative metabolic activation, extending beyond the classical proposed mechanisms of vitamin D’s role in calcium homeostasis and immune regulation. This new evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between vitamin D3 signaling and regulation of circadian networks via interactions with nuclear receptors such as RORs, REV-ERBs, and AhR, providing a plausible link between UVB-dependent vitamin D synthesis, seasonal variation, and molecular clock mechanisms [32]. These insights complement established evidence that adequate vitamin D levels are critical for maternal and fetal health, particularly through calcium metabolism and immune regulation. Inadequate maternal vitamin D levels may impair calcium absorption and placental calcium transfer, disrupting fetal skeletal mineralization and contributing to adverse growth outcomes [8, 27, 28]. Additionally, vitamin D has been implicated in immunomodulation, where deficiency is associated with inflammatory activity alteration and increased susceptibility to neonatal infectious complications [8, 24, 26]. Beyond the classical 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D pathway, CYP11A1-initiated activation of vitamin D3 and related photoproducts produces hydroxyderivatives that act on non-classical receptors, including RORα/γ, AhR, and LXR, potentially influencing inflammation and cellular differentiation [33]. While direct evidence of this relationship among pregnant mothers is lacking, these pathways suggest plausible mechanisms linking seasonal variation in maternal vitamin D status to fetal growth, immune function, and neonatal health outcomes. However, their contribution in our cohort remains speculative.

The implications of these findings are significant for clinical and public health efforts. Given the seasonal variations in vitamin D deficiency, monitoring serum 25(OH)D levels in pregnant women, particularly during winter months or in regions with limited sun exposure, may help prevent deficiency and its associated risks. Establishing clinical guidelines regarding supplementation, increasing awareness of supplementation adherence, and encouraging intake of vitamin D-rich foods, could be particularly beneficial, especially in regions where deficiency is widespread. Since maternal vitamin D levels directly impact fetal development [34], ensuring adequate vitamin D intake during pregnancy could reduce the incidence of neonatal complications and improve outcomes related to overall fetal growth, bone health, and immune function. Public health initiatives, such as promoting year-round supplementation, food fortification, and improved guideline recommendations for adequate vitamin D intake, could help mitigate vitamin D deficiency and these associated risks, leading to improved maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation strategies, including optimal duration, timing, and dosage, to determine the most efficient approach for preventing vitamin D deficiency and improving health outcomes. Large-scale longitudinal studies could help clarify the role of vitamin D in preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes, providing valuable insights for clinical and public health policies. Understanding the relationship between maternal vitamin D levels and neonatal health may help refine targeted interventions, ensuring better health outcomes for both mothers and infants.

Limitations and strengths

This systematic review includes studies from a myriad of regions including China, Ireland, Turkey, Japan, Slovenia, Morrocco, South Africa, United States, Ireland, and South Korea. This poses both strengths and limitations to the systematic review.

For instance, the quantitative threshold for hypovitaminosis is not a fixed universal value. Thus, serum levels defined as vitamin D deficiency are not a standardized threshold value, which may lead to some confounding inconsistencies in our findings. Also, the actual methods of obtaining and measuring vitamin D levels were not standardized across all studies, which may lead to some inconsistencies in accuracy of serum 25(OH)D levels reported. There was also variation in sample size and demographics among the studies included in the systematic review. For example, a study conducted in St. Louis, Missouri consisted of a sample size of 66 pregnant women, while another study conducted in Turkey reported a sample size of 600 mother-infant pairs. These drastic fluctuations in sample size, and lack of standardization, may contribute to inconsistencies.

Additionally, the vast array of geographic locations and countries included in the systematic review results in variable duration and timing of seasons, climate, and average amount of daylight. Thus, based on the variation in proximity to the equator, the average amount of daylight varies by country and may lead to variation in sun exposure and corresponding maternal vitamin D levels. Also, the studies included in this systematic review lack clarity as to whether vitamin D supplementation was addressed or restricted. This could result in some inconsistencies in our efforts to assess the most direct relationship between season and maternal serum 25(OH)D levels. Lastly, while conducting the systematic review, the full text secondary review was not blinded. This has the potential to introduce some confirmation bias among the authors during the full text secondary review process.

Nonetheless, given the objective of this systematic review, it is not possible to standardize every variable. Additionally, when it comes to assessing neonatal outcomes, this systematic review focuses on specific, yet universal outcomes that facilitate the establishment of a relationship between seasonal maternal serum 25(OH)D levels and neonatal outcomes. There are tradeoffs to every scenario and this systematic review takes a holistic, universal approach toward investigating the correlation between maternal vitamin D levels and neonatal outcomes.

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

This systematic review reveals significant seasonal variation in maternal vitamin D levels, with lower levels typically observed in the winter and higher levels in the summer. These fluctuations are consistent across geographic regions and were largely attributed to changes in sunlight exposure. While some research demonstrated associations with adverse neonatal outcomes, such as SGA and preterm birth, others found no correlation, exposing the inconsistency in the relationship between maternal vitamin D levels and neonatal outcomes. These discrepancies are likely due to factors such as study design, cultural practices, population demographics, and regional differences. In areas of more consistent sun exposure, vitamin D deficiency persists, likely due to supplementation limitations or lifestyle differences, although the seasonal variations in vitamin D levels are less pronounced. To address deficiency in vitamin D, especially in areas further from the equator or with limited sun exposure, clinicians should emphasize consistent supplementation use and adherence, as well as monitoring of vitamin D status. Further research is needed to better refine the supplementation protocols and strategies, and to better understand the impact it has on maternal and neonatal outcomes, with the ultimate goal of reducing global vitamin D deficiency and its associated risks.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Beth Bailey PhD for her mentorship in this research project. The authors also thank Rebecca Renirie for their contributions in crafting our search terms and advice on accessing databases.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors developed the research question and conducted initial literature review. AR retrieved articles from PubMed, CINHAL, Cochrane Library, and Scopus. AR managed the inclusion/exclusion database. All authors independently reviewed subsection of titles and met to break ties. All authors divided the remaining articles and conducted full review and extraction. Any opposing opinions were discussed and decided upon by all authors. AR managed the extraction database. NA organized the assessment of risk bias. All authors divided and rated the included articles. Any discrepancies were discussed and agreed upon unanimously. All authors have approved this manuscript. Specific contributions are as follows: NA wrote methods, key messages, and partial results; SE wrote abstract, partial results, and limitations/strengths; AR wrote introduction, partial results, and references; MS wrote partial results, discussion, and conclusion.

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

25(OH)D: 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CI: confidence interval; CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; MeSH: Medical Subject Headings; MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; PICO(T): Patient/Population/Problem Intervention Comparison Outcome Timeframe; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SGA: small for gestational age; UVB: ultraviolet B; Vit. D: vitamin D

| References | ▴Top |

- Lam DA, Miron JA. Seasonality of births in human populations. Soc Biol. 1991;38(1-2):51-78.

doi pubmed - Doyle MA. Seasonal patterns in newborns' health: Quantifying the roles of climate, communicable disease, economic and social factors. Econ Hum Biol. 2023;51:101287.

doi pubmed - Fahey CA, Chevrier J, Crause M, Obida M, Bornman R, Eskenazi B. Seasonality of antenatal care attendance, maternal dietary intake, and fetal growth in the VHEMBE birth cohort, South Africa. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222888.

doi pubmed - Strand LB, Barnett AG, Tong S. The influence of season and ambient temperature on birth outcomes: a review of the epidemiological literature. Environ Res. 2011;111(3):451-462.

doi pubmed - Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D [Internet]. [cited Nov 19, 2025]. Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/.

- Carnevale V, Modoni S, Pileri M, Di Giorgio A, Chiodini I, Minisola S, Vieth R, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of vitamin D status in healthy subjects from southern Italy: seasonal and gender differences. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(12):1026-1030.

doi pubmed - Thorne-Lyman AL, Fawzi WW. Vitamin A and carotenoids during pregnancy and maternal, neonatal and infant health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(Suppl 1):36-54.

doi pubmed - Mulligan ML, Felton SK, Riek AE, Bernal-Mizrachi C. Implications of vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and lactation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):429.e421-429.

doi pubmed - Perez-Lopez FR, Pasupuleti V, Mezones-Holguin E, Benites-Zapata VA, Thota P, Deshpande A, Hernandez AV. Effect of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(5):1278-1288.e1274.

doi pubmed - Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

doi pubmed - Walsh JM, Kilbane M, McGowan CA, McKenna MJ, McAuliffe FM. Pregnancy in dark winters: implications for fetal bone growth? Fertil Steril. 2013;99(1):206-211.

doi pubmed - Dovnik A, Mujezinovic F, Treiber M, Pecovnik Balon B, Gorenjak M, Maver U, Takac I. Determinants of maternal vitamin D concentrations in Slovenia : A prospective observational study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2017;129(1-2):21-28.

doi pubmed - Ocal DF, Aycan Z, Dagdeviren G, Kanbur N, Kucukozkan T, Derman O. Vitamin D deficiency in adolescent pregnancy and obstetric outcomes. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;58(6):778-783.

doi pubmed - Velaphi SC, Izu A, Madhi SA, Pettifor JM. Maternal and neonatal vitamin D status at birth in black South Africans. S Afr Med J. 2019;109(10):807-813.

doi pubmed - Ates S, Sevket O, Ozcan P, Ozkal F, Kaya MO, Dane B. Vitamin D status in the first-trimester: effects of Vitamin D deficiency on pregnancy outcomes. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(1):36-43.

doi pubmed - Li H, Ma J, Huang R, Wen Y, Liu G, Xuan M, Yang L, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the pregnant women: an observational study in Shanghai, China. Arch Public Health. 2020;78:31.

doi pubmed - Choi R, Kim S, Yoo H, Cho YY, Kim SW, Chung JH, Oh SY, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant Korean women: the first trimester and the winter season as risk factors for vitamin D deficiency. Nutrients. 2015;7(5):3427-3448.

doi pubmed - Hillman LS, Haddad JG. Human perinatal vitamin D metabolism. I. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in maternal and cord blood. J Pediatr. 1974;84(5):742-749.

doi pubmed - Shibata M, Suzuki A, Sekiya T, Sekiguchi S, Asano S, Udagawa Y, Itoh M. High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in pregnant Japanese women with threatened premature delivery. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29(5):615-620.

doi pubmed - Loudyi FM, Kassouati J, Kabiri M, Chahid N, Kharbach A, Aguenaou H, Barkat A. Vitamin D status in Moroccan pregnant women and newborns: reports of 102 cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:170.

doi pubmed - Treiber M, Mujezinovic F, Pecovnik Balon B, Gorenjak M, Maver U, Dovnik A. Association between umbilical cord vitamin D levels and adverse neonatal outcomes. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(10):300060520955001.

doi pubmed - Zhang H, Wang S, Tuo L, Zhai Q, Cui J, Chen D, Xu D. Relationship between maternal vitamin D levels and adverse outcomes. Nutrients. 2022;14(20):4230.

doi pubmed - Ozias MK, Kerling EH, Christifano DN, Scholtz SA, Colombo J, Carlson SE. Typical prenatal vitamin D supplement intake does not prevent decrease of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D at birth. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(5):394-399.

doi pubmed - Cui A, Xiao P, Ma Y, Fan Z, Zhou F, Zheng J, Zhang L. Prevalence, trend, and predictor analyses of vitamin D deficiency in the US population, 2001-2018. Front Nutr. 2022;9:965376.

doi pubmed - Ames BN, Grant WB, Willett WC. Does the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in African Americans contribute to health disparities? Nutrients. 2021;13(2):499.

doi pubmed - Karras SN, Fakhoury H, Muscogiuri G, Grant WB, van den Ouweland JM, Colao AM, Kotsa K. Maternal vitamin D levels during pregnancy and neonatal health: evidence to date and clinical implications. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2016;8(4):124-135.

doi pubmed - Mansur JL, Oliveri B, Giacoia E, Fusaro D, Costanzo PR. Vitamin D: Before, during and after Pregnancy: Effect on Neonates and Children. Nutrients. 2022;14(9):1900.

doi pubmed - Shin YH, Yu J, Kim KW, Ahn K, Hong SA, Lee E, Yang SI, et al. Association between cord blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and respiratory tract infections in the first 6 months of age in a Korean population: a birth cohort study (COCOA). Korean J Pediatr. 2013;56(10):439-445.

doi pubmed - Specker B. Vitamin D requirements during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1740S-1747S.

doi pubmed - Kaushal M, Magon N. Vitamin D in pregnancy: a metabolic outlook. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(1):76-82.

doi pubmed - Scully H, Laird E, Healy M, Crowley V, Walsh JB, McCarroll K. Low socioeconomic status predicts vitamin D status in a cross-section of Irish children. J Nutr Sci. 2022;11:e61.

doi pubmed - Slominski AT, Slominski RM, Kamal M, Holick MF, Tuckey RC, Reiter RJ, Li W, et al. Is vitamin D signaling regulated by and does it regulate circadian rhythms? FASEB J. 2025;39(24):e71321.

doi pubmed - Slominski AT, Kim TK, Janjetovic Z, Slominski RM, Li W, Jetten AM, Indra AK, et al. Biological effects of CYP11A1-derived vitamin D and lumisterol metabolites in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2024;144(10):2145-2161.

doi pubmed - Gilani S, Janssen P. Maternal vitamin D levels during pregnancy and their effects on maternal-fetal outcomes: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42(9):1129-1137.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.