| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcgo.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 2, June 2025, pages 69-74

Human Metapneumovirus as a Cause of Severe Respiratory Illness in the Second Trimester of Pregnancy: Two Cases

Manvitha Manyama , Cameron Jacksona, e

, Amalia Brawleyb

, Martha Cohenc, Harold Katnerd

, Padmashree C. Woodhamb

aMedical College of Georgia, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA

bDivision of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA

cLowCountry Women’s Specialists, Summerville, SC 29485, USA

dDepartment of Infectious Disease, Mercer Medicine, Macon, GA 31201, USA

eCorresponding Author: Cameron Jackson, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA

Manuscript submitted June 3, 2025, accepted June 27, 2025, published online July 8, 2025

Short title: hMPV Causes Severe Illness Second Trimester

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo1523

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Despite being a fairly common cause of respiratory infection in adults, there have been few reported cases of human metapneumovirus (hMPV) in pregnancy. Other viruses, such as influenza, have been heavily reported on, and it is well established that these illnesses are detrimental to the pregnant population. However, we currently have limited data about hMPV’s effect. First, we discuss the case of a patient who presented to the emergency department in the second trimester with severe shortness of breath and was ultimately diagnosed with hMPV. Second, we discuss the case of a patient who presented as an intensive care unit transfer in the second trimester in severe respiratory distress with a positive test for hMPV at the outside facility. These cases highlight the fact that inpatient management might be needed to treat hMPV in pregnant patients, even for those without a significant prior respiratory medical history. Given the limited number of published cases of hMPV in the antepartum patient population, we hope to provide guidance for management of such cases and highlight the importance of prompt diagnosis in pregnant populations.

Keywords: Human metapneumovirus; Second trimester pregnancy; Pregnancy; Respiratory tract infections; Viral pneumonia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) has been identified as a cause of mild to moderate respiratory illness that primarily affects children, but also accounts for approximately 1.5-10.5% of respiratory infections among adults [1]. hMPV is a member of the Paramyxovirus family and is an enveloped, non-segmented, negative sense, single-stranded RNA virus known to be an etiology of both upper and lower respiratory tract infections [2]. As with most respiratory viruses, there is somewhat of a seasonality to metapneumovirus infections, with the majority of cases occurring at the time of annual community outbreaks of other respiratory viruses, primarily during the late fall, winter, and early spring [2]. Current theories suggest that hMPV is transmitted via respiratory droplets and close personal contact [3]. Diagnosis of hMPV is confirmed via direct detection of the viral genome by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays or by other methods, but is not commonly performed in clinical practice. The current multiplex PCR assay does not include hMPV; thus, the true disease burden is not well identified. A 2017 study estimated that 17.2% of non-asthmatic pregnant patients presenting with upper respiratory symptoms were positive for hMPV by PCR testing [1]. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, among consistently reporting laboratories from 2008 to 2014, 3.6% of all specimens from pediatric populations were positive for hMPV, while approximately 15.3% and 18.2% were positive for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza, respectively [2].

Respiratory illness is relatively common in pregnant populations, and complications like secondary bacterial pneumonia may occur. Data from a 2018 cross-sectional surveillance study illustrated that human rhinovirus, coronaviruses, RSV, and influenza were the most common infectious etiologies of respiratory symptoms in pregnant patients during the second and third trimesters, in that order [4]. Pregnant patients who contracted influenza A during the 2009 pandemic had higher rates of secondary bacterial pneumonia and increased risk of inpatient and intensive care unit (ICU) admission, especially those in the third trimester. These patients also had higher rates of fetal growth restriction, stillbirth, miscarriage, and preterm birth [5]. Human rhinovirus, coronaviruses, RSV, and influenza were followed by hMPV as the most common etiologies of respiratory symptoms during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, causing two of the 81 reported cases of respiratory illness according to one single-institution study [4].

Despite this, there remain limited data regarding hMPV specifically in the context of pregnancy. Currently, there are no documented cases of hMPV diagnosis in the second trimester of pregnancy. Pregnant patients presenting with respiratory illness in the second trimester have the potential to quickly decline and become medically unstable. The differential diagnosis for these patients can be quite broad, and often less-known viral illnesses such as hMPV may be inadvertently omitted. Given the lack of reported cases of hMPV during the second trimester of pregnancy in the current literature, it is important that physicians include this etiology in their differential diagnosis. The significance of this case series lies in its ability to expedite diagnosis, conserve resources used to obtain a diagnosis, and provide the appropriate symptomatic treatment necessary for patients to fully recover from this viral illness.

| Case Reports | ▴Top |

Case 1

Investigations

This is the case of a 49-year-old G9P2234 who presented to the emergency department (ED) at 19 weeks 1 day gestation with severe shortness of breath. The patient had previously presented to the ED approximately 2 days prior with similar concerns of difficulty breathing and shortness of breath. She denied any other upper respiratory symptoms including cough, sore throat, rhinorrhea, hemoptysis, etc. She also denied fever and other systemic symptoms. She had wheezing on exam, but no rales. She was eventually discharged home upon receiving an albuterol breathing treatment, which resulted in symptom improvement. Upon subsequent presentation 2 days later, given her gestational age and persistent symptoms, the Maternal Fetal Medicine team was consulted for inpatient admission and management. On initial interview, the patient denied ever experiencing similar shortness of breath in the past. She denied any history of respiratory disease including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma. She also denied any recent known exposure to sick contacts. Her vital signs were within normal limits with oxygen saturation ranging from 96% to 100% on room air.

Diagnosis

Chest X-ray and electrocardiogram were immediately performed, and both were within normal limits. Laboratory studies including complete blood count, chemistry panel, and brain natriuretic peptide returned within normal limits. As her workup was benign thus far, there was not yet a definitive diagnosis allowing for directed treatment of the patient’s respiratory illness. Pulmonology and Cardiology were consulted upon admission and a Biofire respiratory panel was added to previously ordered laboratory studies. This panel consists of a nasal swab that tests for several respiratory pathogens including hMPV, and it returned positive for hMPV.

Treatment

The patient was acutely given ipratropium and albuterol nebulizer treatment, intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone, and IV ampicillin while in the ED in an attempt to improve her respiratory status before final diagnosis was made. Thereafter, Infectious Disease specialists were consulted for further management recommendations given the limited available information about treatment of hMPV during pregnancy. The patient was managed with symptomatic treatment, consisting of 48 h of IV steroids followed by oral steroids, acetaminophen, and diphenhydramine, until she demonstrated clinical improvement. She was also kept on strict contact precautions while symptomatic via the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and hospital guidelines.

Follow-up and outcomes

Eight days later, the patient was discharged home after all her symptoms resolved, with a prescription to complete the remaining days of her oral steroid taper at home and with close follow-up in the High-Risk Obstetrics Clinic. She went on to deliver at term at an outlying hospital, and the health status of her baby was unable to be obtained.

Case 2

Investigations

This is the case of a 22-year-old G2P0101 with past medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and chronic hypertension who presented to the ED at an outside hospital (OSH) at 24 weeks 5 days gestation. Originally, her symptoms included a cough and mild upper respiratory symptoms. She presented to the ED at the OSH upon worsening of shortness of breath, chest pain, and lower extremity edema, 5 days after the original symptom onset. Her “toddler-age” child had known history of upper respiratory infection prior to presentation at the OSH, and the patient and her child both developed nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea earlier that week. At the OSH, she developed acute hypoxic respiratory failure. Of note, she had no known history of asthma, COPD, or other underlying respiratory comorbidity.

Diagnosis

Upon evaluation at the OSH, a respiratory panel was obtained and returned positive for hMPV. Chest X-ray demonstrated right lower and middle lobe pneumonia. She received one dose each of ceftriaxone and azithromycin. She was then transitioned to meropenem and azithromycin. Despite these interventions, her clinical condition continued to worsen; she was given diuretics due to concern for possible fluid overload superimposed upon pneumonia. She continued to decompensate and developed acute hypoxic respiratory failure. Arterial blood gas (ABG) was drawn and demonstrated concern for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). She required intubation, mechanical ventilation, and ultimately prone positioning. She was then transferred to our facility at 24 weeks 6 days gestation for further management. At our facility, influenza and RSV swabs were negative. Blood culture, urine culture, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture were all negative for growth; BAL Gram stain showed no organisms.

Treatment

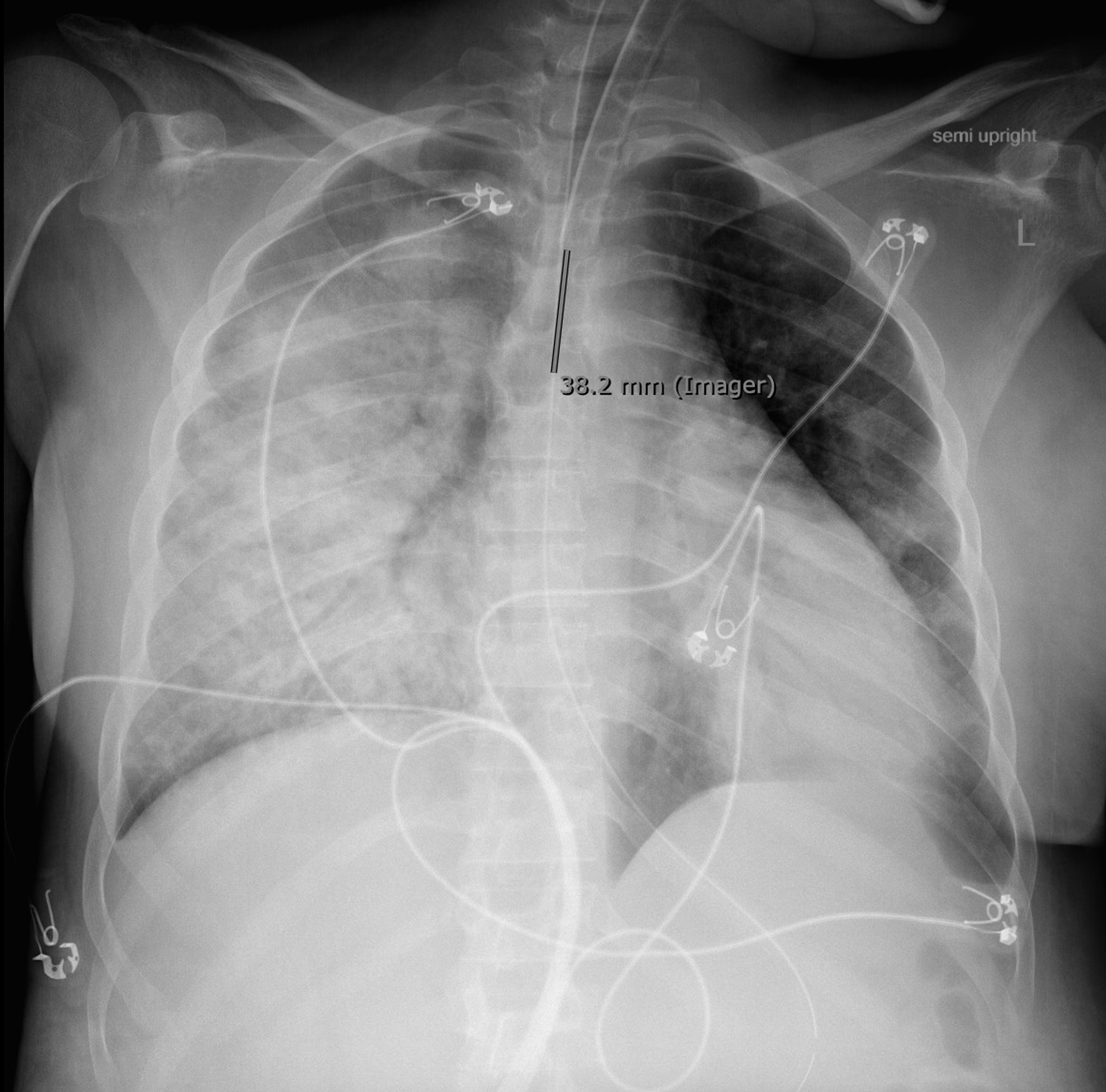

The patient arrived at our facility intubated and on blood pressure support. On arrival, continuous fetal monitoring demonstrated minimal variability, absent accelerations, and absent decelerations. She received IV dexamethasone for ARDS and was placed in the prone position. She received bicarbonate for continued acidosis. Chest X-ray demonstrated “right greater than left airspace consolidations with superimposed air bronchograms” (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Chest X-ray upon admission. |

As maternal condition continued to worsen, continuous fetal monitoring evolved to absent variability and prolonged variable decelerations; the patient subsequently underwent cesarean section at 25 weeks 0 days gestation due to non-reassuring fetal condition and maternal oxygen desaturation despite resuscitative measures. Post-operatively, she underwent transthoracic echocardiogram which demonstrated ejection fraction (EF) of 36-40% (etiology unclear), received dialysis for refractory acidosis, and was placed back in the prone position for continued poor respiratory status. On post-operative day (POD) 2, chest X-ray demonstrated “extensive bilateral pulmonary opacities, improved compared to prior” (Fig. 2) and ABG demonstrated resolution of acidosis, therefore the patient was extubated to high flow nasal canula (HFNC).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Chest X-ray on post-operative day 2. |

She was dialyzed once more on POD3 for continued decreased urine output, which then improved, and dialysis catheter was removed. Sedation and oxygen administration were weaned as appropriate. IV dexamethasone was tapered once the patient demonstrated continued clinical improvement. Post-operatively, hypertension was managed with nitroglycerin and was eventually transitioned to anti-hypertensive regimen of nifedipine, hydralazine, and isosorbide dinitrate; however, hypertension remained poorly controlled with systolic blood pressure ranging from 110s to 170s and diastolic blood pressure ranging from 70s to 100s. Diuretics and beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction were titrated and transitioned to oral administration using furosemide and carvedilol. Oxygen requirement continued to decrease, with patient requirement down to 2 L nasal canula (NC).

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient was discharged home on hospital day 12 with prescriptions for bumetanide, carvedilol, isosorbide dinitrate, and nifedipine, as well as home oxygen of 2 L NC and close follow-up with virtual care at home, internal medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology. Outpatient workup was recommended by inpatient management team for resistant hypertension during her hospital stay.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Limited information exists in the literature regarding management and perinatal outcomes in patients diagnosed with hMPV. In fact, the only four reported cases of hMPV in the current literature were diagnosed exclusively in the third trimester, and each patient presented with various symptoms, including respiratory involvement, respiratory decompensation, ICU care, and even cesarean section [6].

Management of hMPV can prove difficult in the antepartum patient, as treatment is primarily symptom driven, and rapid clinical deterioration may occur. The first challenge with hMPV arises with diagnosing this viral illness. Current data about the prevalence of hMPV in pregnancy are limited as it is often not included in the differential diagnosis of respiratory illness. Given the potential for respiratory compromise in these patients, however, it is important to address this upon initial evaluation by ordering appropriate diagnostic tests to promptly establish a clear diagnosis. More frequent testing will also allow for additional data about prevalence of and risk factors for hMPV, which would help guide future treatment protocols. Additionally, increased testing for hMPV will illuminate the true spectrum of disease in pregnancy, which is currently not well defined. Better understanding of hMPV infection outcomes will allow development of tailored treatment plans and/or protocols based on disease severity.

Moreover, although hMPV has been implicated in preexisting lung conditions such as asthma and/or COPD, these patients presented here did not have a history of any significant respiratory conditions [7]. Hence, the extended Biofire respiratory panel should be considered early during management of respiratory symptoms to test for viral illness in pregnant patients, especially those in their second or third trimester. In addition, the requirement for contact precautions, as recommended by the CDC, further lends this patient population to the need for management in the inpatient setting, where these precautions may be enforced more effectively. Care for pregnant patients with hMPV should occur within the inpatient setting that is appropriate for the patient’s acuity.

Currently, no immunization is available for hMPV. Since the discovery of hMPV in 2001, many attempts have been made to develop a vaccine, including trials of inactivated viruses, live-attenuated viruses, recombinant proteins, and DNA-encoding virus proteins, without success [8]. However, vaccines for hMPV are actively in development, with promising results shown in simulation and mice models [9, 10]. The administration of vaccines against other common respiratory pathogens, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), influenza, and RSV, is routinely recommended in pregnancy, with support from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) [11]. Routine vaccination against these respiratory pathogens has shown improved maternal and infant outcomes and remains the standard of care in pregnancy [12]. Given the efficacy of other respiratory vaccines, the need for the development of an effective hMPV vaccine proves critical, in addition to establishing diagnostic and treatment protocols to standardize care for pregnant patients with hMPV infection.

ACOG currently recommends considering both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infection as a part of the differential diagnosis for any pregnant patient presenting with respiratory symptoms [13]. Moreover, it is recommended to begin empiric antiviral treatment with oseltamivir and/or nirmatrelvir and ritonavir within 48 h of symptom onset, even without respiratory infection test results [13]. In contrast, there are limited data and few reported cases of hMPV, and hence, no specific ACOG recommendations to guide diagnostic testing or management. However, there is evidence that in patients with multiple comorbidities, disease can be severe and require ICU care and even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which is further underscored by the cases presented here [2]. Additional guidelines would be helpful to fill this care gap, and for that, we need more testing and diagnosis.

Learning points

This report highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing hMPV in pregnant patients, particularly those in their second and third trimesters. While hMPV is a known cause of respiratory illness, it is often not included in the differential diagnosis for pregnant patients, leading to delayed recognition. First, we report a case of a 49-year-old pregnant patient with severe shortness of breath who was ultimately diagnosed with hMPV after testing with a Biofire respiratory panel, which is recommended for all pregnant patients presenting with respiratory symptoms. Then, we report a case of a 22-year-old pregnant patient who presented with severe respiratory symptoms and was diagnosed with hMPV using a respiratory panel, after which she rapidly decompensated, was diagnosed with ARDS, and required ICU admission and emergent cesarean delivery. The report emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis, symptomatic treatment, and inpatient monitoring for pregnant individuals diagnosed with hMPV, as hMPV can lead to severe respiratory compromise, especially in the presence of comorbidities. This report also stresses the need for more data on the prevalence and risks of hMPV in pregnancy to guide future treatment protocols, as current guidelines primarily focus on influenza and SARS-CoV-2, with limited guidance for hMPV.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Patients’ informed consent for publication of this report was obtained.

Author Contributions

MM, CJ, and AB contributed to the completion of the manuscript and its submission. MC, HK, CJ, and PCW managed the patients and contributed to the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in a password-protected electronic medical record.

Abbreviations

ABG: arterial blood gas; ACOG: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; CDC: Centers of Disease Control and Prevention; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ED: emergency department; EF: ejection fraction; HFNC: high flow nasal canula; hMPV: human metapneumovirus; ICU: intensive care unit; IV: intravenous; NC: nasal canula; OSH: outside hospital; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; POD: post-operative day; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

| References | ▴Top |

- Lenahan JL, Englund JA, Katz J, Kuypers J, Wald A, Magaret A, Tielsch JM, et al. Human metapneumovirus and other respiratory viral infections during pregnancy and birth, Nepal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(8):1341-1349.

doi pubmed pmc - Haynes AK, Fowlkes AL, Schneider E, Mutuc JD, Armstrong GL, Gerber SI. Human metapneumovirus circulation in the United States, 2008 to 2014. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20152927.

doi pubmed - CDC. About human metapneumovirus. 2024. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/human-metapneumovirus/about/index.html.

- Hause AM, Avadhanula V, Maccato ML, Pinell PM, Bond N, Santarcangelo P, Ferlic-Stark L, et al. A cross-sectional surveillance study of the frequency and etiology of acute respiratory illness among pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(4):528-535.

doi pubmed pmc - Englund JA, Chu HY. Respiratory virus infection during pregnancy: does it matter? J Infect Dis. 2018;218(4):512-515.

doi pubmed pmc - Schwartz DA, Dhaliwal A. Infections in pregnancy with COVID-19 and other respiratory RNA virus diseases are rarely, if ever, transmitted to the fetus: experiences with coronaviruses, HPIV, hMPV RSV, and influenza. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144(8):920-928.

doi pubmed - Kan OK, Ramirez R, MacDonald MI, Rolph M, Rudd PA, Spann KM, Mahalingam S, et al. Human metapneumovirus infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact of glucocorticosteroids and interferon. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(10):1536-1545.

doi pubmed - Kruger N, Laufer SA, Pillaiyar T. An overview of progress in human metapneumovirus (hMPV) research: structure, function, and therapeutic opportunities. Drug Discov Today. 2025;30(5):104364.

doi pubmed - Ma S, Zhu F, Xu Y, Wen H, Rao M, Zhang P, Peng W, et al. Development of a novel multi-epitope mRNA vaccine candidate to combat HMPV virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(3):2293300.

doi pubmed pmc - Trinite B, Durr E, Pons-Grifols A, O’Donnell G, Aguilar-Gurrieri C, Rodriguez S, Urrea V, et al. VLPs generated by the fusion of RSV-F or hMPV-F glycoprotein to HIV-Gag show improved immunogenicity and neutralizing response in mice. Vaccine. 2024;42(15):3474-3485.

doi pubmed - ACOG. COVID-19 vaccination considerations for obstetric-gynecologic care. 2020, updated June 4, 2025. Available at: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/covid-19-vaccination-considerations-for-obstetric-gynecologic-care.

- Phijffer EW, de Bruin O, Ahmadizar F, Bont LJ, Van der Maas NA, Sturkenboom MC, Wildenbeest JG, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination during pregnancy for improving infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;5(5):CD015134.

doi pubmed pmc - ACOG. Influenza in pregnancy: prevention and treatment. 2024. Available at: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-statement/articles/2024/02/influenza-in-pregnancy-prevention-and-tsreatment.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.